by Jonathan Kalb

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

Gilman’s signal teaching talent was showing others how to read their own writing well, which he called an “indispensable skill.” His and Kauffmann’s “Crit Workshops” at the Yale School of Drama—required every semester for three years—were tiny, intensive seminars devoted to upping our games. We crit students venerated these men because we wanted what they had: perches at the increasingly rare prestigious intellectual weeklies (such as The Nation and The New Republic) that were surviving the withering assaults of the media age in the 1980s. Each three-hour Crit session focused on a single student paper. Dick (as he introduced himself) never bothered with written comments. In his classes, he’d read the paper aloud in its entirety, leaning back in his plastic chair, chain-smoking cigarillos, and channel the writer’s voice with his own inflections, like a Brechtian actor supplementing a role with his savvy persona. Thus he performed the model intellectual, articulating, in a stream of unsparing interruptions and digressions, the manner and temper of the “generally intelligent mind” we were told we should write for.

This was a thrilling and terrifying experience. Dick would stop to remark on any formulation, image, or thought that bothered him, not only flagging our dangling participles, flaccid metaphors, and baggy digressions but also speculating on the reasons for them. He’d ask tetchily about our intentions and then, with biting humor, pronounce Olympian verdicts on our evasions, confusions, pretentions, and oceanic ignorance. This painful, merciless crucible was everything I’d hoped for from that storied school.

An ambitious kid from a chaotic family, I craved exposure to disciplined minds and wanted to know how my mind measured up. The peevish precepts he tossed out willy-nilly in that class have stayed with me for a lifetime. His insistence that puffy PR-speak amounts to “verbal inflation” and should be reined in by force, for instance: “if I were the Czar I’d put a use tax on ‘amazing,’ ‘astonishing,’ and ‘fabulous.’” Or his observation that the final item in any sequence of three should always be “fresh, surprising, and Chekhovian.” Dick made us feel like initiates to an ancient guild, now entrusted with trade secrets we might do magic with, if we were able.

Alas, Crit Workshop was the sole teaching arena in which he shone, at least in my time. In pretty much all else, he was a neglectful fuckup. His older daughter, in her new memoir about him, describes the emotional tailspin he was in then following a devastating divorce in 1980, and she’d probably put his sorry treatment of my cohort down to understandable depression. I’m sure that was a factor, but so was his ego. Dick came from humble, Brooklyn-Jewish roots, he was a gumptious auto-didact with only an undergraduate degree, but by the 1960s he was married to the high-powered literary agent Lynn Nesbit, writing for Newsweek and Partisan Review, and securely ensconced in the New York literary aristocracy. He moved in the glitziest circles, as he never tired of reminding us, palling around with the likes of Anatole Broyard, Bernard Malamud, Jane Kramer, Ann Beattie and Toni Morrison. He was courted everywhere for advice and approval. Dick came to feel that that status entitled him to write full-time, and he oozed resentment at having to teach to earn a living. He also had an insidious inferiority complex about academia that manifested in contempt for its various structures and expectations.

For some reason, he respected Crit Workshop, establishing it as a line of dereliction he wouldn’t cross, but he devoted as little prep time as possible to his other classes. The brilliant author of The Making of Modern Drama—an extraordinarily erudite and elegantly written book that I adored, and that was nominated for the National Book Award—organized whole-semester classes on a handful of plays and assigned no secondary reading. Discussions with him were often meandering, desultory affairs that he’d perk up with literary quotes read from a pile of old index cards he carried around. Those cards were like nitro pills he compulsively popped whenever he felt the need to revive his class’ flagging heart. Dick could be gentle, ebullient, and charming, but he was utterly unreliable and often cruel, petty, distracted, and envious. He slept with his students, with impunity, wore his personal wounds like badges of pride, and made everyone in his orbit feel responsible for nursing them.

I knew all of this, reader, and yet chose him as a dissertation advisor. The result was beyond even my imagining. He’d expressed paternal affection for me, we’d shared school gossip and misery over the New York Mets when I was his pickup driver one term, and I flattered myself we had a connection. I wrote my dissertation on Samuel Beckett while living in West Berlin in 1986-87 (my future wife Julie generously shared her Fulbright Grant with me), and I sent Dick my chapters as I completed them throughout the year, as we’d agreed. He never even acknowledged the envelopes. Or the letters I sent jubilantly describing two meetings I arranged with Beckett. Nor would he return my calls after I returned to the States. He ignored me for fifteen months, finally reading my manuscript only after Kauffmann told him it was accepted for publication as a book by Cambridge University Press. He did eventually apologize, in an agonized, self-piteous phone call a year later after learning my book had won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism.

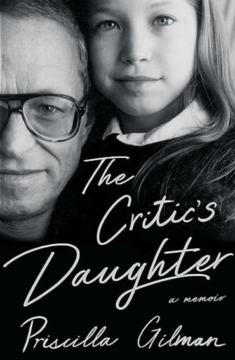

Priscilla Gilman’s The Critic’s Daughter is in many ways a remarkable document. Much of it is a bracingly honest, penetrating, absorbing, and occasionally harrowing tale of mistreatment far more consequential than anything I suffered. She is a gifted memoirist with an eye for the lacerating detail, an uncannily prodigious memory, and an intelligent heart more generous than Dick probably deserved. Yet there are also a few jangling false notes in this self-evidently therapeutic book.

Full disclosure: Priscilla thanks me, along with many other former students of her dad’s, in her acknowledgements. I don’t know why. I’ve met her three or four times over the years and exchanged occasional emails and Facebook “likes” with her. We once cooperated on an effort to stop a former student plagiarizing her father. That’s about it. We’ve never had a substantial conversation.

Which brings me to the first false note. On the evidence of this book, there’s no way to tell if Priscilla ever had a substantial conversation with any of Dick’s other students either. She refers to us often, but with a child’s eye, as an undifferentiated pack of adoring acolytes. Here she is describing a visit to one of her dad’s classes as an applicant to Yale College: “The students revered him, it was clear, they wanted to please him, impress him, wow him, but they also had a tender affection for him . . . seeing how they loved him made me feel he had a whole flock of surrogate children at Yale who were doing some of the buffering and bolstering [my sister] Claire and I had always done.” This is a serious blind spot. Priscilla never questions the performed idolatry of that “flock” or seeks to look behind it. That is important because it keeps her from seeing how much her father’s story resonates with the debates swirling around criticism in our time.

Priscilla established her own writerly reputation with an extraordinary 2011 book called The Anti-Romantic Child: A Memoir of Unexpected Joy, which recounts her experience mothering a special-needs child. Her son Benjamin (Benj) was born with hyperlexia, a form of autism, and the book interweaves the tale of discovering and coping with his condition—the stress, the medical and educational trials, the adjusted life expectations that ensued—with reflections on Priscilla’s upbringing, her parents’ unaffectionate marriage and divorce, her divorce, and her decision to leave academia after earning a Ph.D. in English literature and teaching at Vassar. The memoir is dense with quotations from romantic poetry, especially Wordsworth, wielded with acuity and flair. That literature was a focus of her academic work, and it served as a kind of life guide for her before motherhood, expressing a fluid, intuitive, spontaneous relationship to childhood, language, expression, nature and love that her new parenting reality complicated forever. The Anti-Romantic Child is deeply moving. Its descriptions of disappointment as a prod to the imagination are inspiring and courageous, and its portrait of a fiercely persistent mother determined to identify every possible means of reaching her strange, remote child is unforgettable. To anyone who knew the cerebrally insular Dick, her exuberant, irrepressible relatedness to others particularly stands out.

The Critic’s Daughter is a different animal, primarily because Priscilla is far more conflicted about her father than about her son. This book is an attempt to shore up Dick’s reputation—she quotes him as glowingly and incessantly as she did Wordsworth, and says, “I don’t want my father’s light . . . to die away”—while also recounting decades of willfully oblivious, manipulative, and pernicious behavior. “This book is an attempt at exorcism at the same time that it is a plea to be haunted,” she writes, unfazed by the contradiction. She wants to praise her father’s ghost and bury it too.

The memoir portrays Dick as the protagonist of a five-act play in which the author is first his darling, then his pupil, and finally his judge. A fairy-tale opening section (“Act 1—Apparelled in Celestial Light”) mushily romanticizes the professionally successful father of two young girls as sublimely playful and imaginative—Willy Wonka-like. But then the complications begin (“Act 2—The Wounded Giant”), and they pile up with such disturbing quantity and force that they assert themselves as the book’s true spurs. According to Priscilla, both her parents acted abominably when they split up. It was Lynn who asked for a divorce, and Dick then withdrew into despondency and a prolonged writer’s block. Huddling with ten-year-old Priscilla in his office, he said to her: “Sometimes I think I’d kill myself if it weren’t for you girls!” She burst into tears, never forgot his words, and thereafter considered his survival her personal responsibility. Lynn (described throughout as cold, pragmatic and un-nurturing) then pulled her aside herself and said: “I want you to know something about your father. He had affairs during our marriage,” but they were “a relief to me. These women took him off my hands! They gave him what I couldn’t.” Also: “Your father was impotent a lot of the time. You know what that means, right, sweetheart?” A swift end to childhood.

Admittedly, this is mild stuff compared to what passes as family trauma in the age of oversharing, and sunny Priscilla cuts the darkness with many rosy memories about the joy of talking books and writing with her dad, but the cumulative weight of the baleful incidents grows. Every period of her life after the divorce is described as in some way freighted with distractions and disruptions when she set aside significant plans (including postponing graduate work) to prop her father up, nurse him, research his diseases, keep tabs on him, run errands for him, and generally worry about him. He invited and encouraged this solicitude and treated it as normal, even after meeting the woman who would become his new wife. This intense co-dependency caused lasting damage. Priscilla had a breakdown at one point, and describes her psychotherapy as follows:

Dr. T was struck by the fact that I’d never complained or cried or told my father how he scared me, hurt me, disgusted me . . . But even as Dr. T nurtured me in ways my parents hadn’t, he himself needed nurturing. His wife was dying of breast cancer . . . He often fell asleep during our sessions; he’d call me “Patricia” at least fifty percent of the time. I never corrected him and sometimes found myself going along with whatever he said even if I disagreed with it, because I wanted to be a good, easy patient . . . My father had trained me well.

This behavior pattern ended up blighting her love life, she says, leading her to avoid “men who were whole, healthy, and secure,” and prefer “damaged, charismatic, complicated men who reminded me of him”—“mercurial, artistic men plagued by insecurity, addictive tendencies, anger issues, or all three” who expected her to “nurture, bolster [and] save them.” It sure is hard to imagine any smart, sensitive young person of today reading all this and thinking, “I have to run and look this guy up!”

Dick is worth looking up; Priscilla is right about that. At his best he represented the apogee of an adventurous, risky, hard-edged but resolutely undogmatic sort of exploratory criticism he once described in an essay on Susan Sontag as “a form of continuing, engaged, philosophically informed aesthetic thinking.” Like other fine essayists of his time (Trilling, Howe, McCarthy), he took all of society as his subject and embarked on truth-seeking journeys of the self to reach his opinions. Dick had uncommon integrity, treating the machinery of stardom with contempt even though he was a star himself. He loved difficult, challenging modern writing, film and theater and saw himself as a preeminently qualified guide through it—his prickliness being a prime qualification because that was also a defining trait of the modern trailblazers. There is unique, enduring light in all his books—even in his weakest, Faith, Sex, Mystery, a socially clueless, navel-gazing memoir about his youthful conversion to Catholicism that lifted him out of his writer’s block.

The one quality in Dick that is hopelessly dated is his unflappable certainty that he belonged to an aristocracy of mind whose superiority of judgment was self-evident. He was part of the last generation of critics to write for a large, homogeneous, aspirational middle class that lionized its high-culture arbiters and consequently often bloated them with arrogance. These pundits had good reason to believe their authority was secure, because their efforts to shape public opinion were widely welcomed and applauded. It was Dick’s dubious luck to be felled by illness right when the leveled and fractured landscape of our time was taking shape, where everyone is a critic, no one’s authority is ever secure, and the very idea of a general public is obsolete. This Tik-Tok-y world, in which even well-educated people are made to feel that some form of glib superficiality is their only possible path to visibility, would’ve baffled and repulsed him.

It’s curious that Priscilla never says a word about the asteroids of pop culture and the internet that obliterated the climate in which “all-powerful, terrifying beings” like her father once thrived as apex opinionators. Her scholarly expertise is in early criticism and she might have been able to historicize the recent extinction. Her dissertation was on the first generation of English literary critics to acquire sufficient power to affect public opinion in the late 18th/early 19th centuries, causing widespread fear and anxiety. William Cowper, for instance, remarked then that “the frown of a critic freezes my poetical powers.” The class of mandarin connoisseurs Dick proudly belonged to was the successor to these early critics, and the Victorian sages, belle-lettrists and 20th-century scholar-critics who followed them; all built their fear-inducing prestige on the same claim that their work was comparable in value and substance to the literature they considered.

Today the social consensus that sustained that claim, and therefore the pundit-critics’ two-century-old authority, has broken down. Where no center of cultural value holds, no path to prestige or stardom is possible in articulating personal judgments. Even commentators with relatively large readerships invariably feel (in John Donatich’s memorable phrase) like “public ineffectuals.”

Which brings me to the other false notes in Priscilla’s book that clank in the many sections where she speaks more as an agent’s daughter than a critic’s, name-dropping every luminary in the smart set her father moved in and leaning hard on blurb-like tropes of power to affirm his cultural status. Dick was “an enormously powerful figure, a fount of wisdom, a locus of authority.” She knows better than this, as she amply demonstrates elsewhere. She’s also surely aware that some of the finest critics of our age have been making peace with their humbler circumstances and producing first-rate work for smaller audiences who still care (in, say, Four Columns, Ann Kjellberg’s Book Post, or Kill Your Darlings).

Whatever the intellectual losses and obstacles of our time (and not to underplay the new forms of brutality, deception and monopoly control), we can hopefully agree that the openness of our public conversation to a vast array of diverse new voices is in principle a good thing. And so is the obligation institutions of higher learning now feel to take action when narcissistic star faculty flagrantly neglect, abuse, and sexually harass students. Tough love teaching, I suppose, will always have its defenders, particularly as long as class war rages against privileged snowflakes, but to those who would leap to exonerate Dick on this basis I’d offer this reflection. Three decades of teaching have left me keenly and humbly aware that students—even exceptionally talented ones—learn in many different ways, and they deserve teachers flexible enough to respond to that. How many of those who were discouraged or intimidated by prickly Dick over the years, or who turned to different career paths because they were unwilling to stroke him, or did stroke him, might have turned out fine critics after all with another guide? Integrity for this troubled man meant truth—his own—at all costs.

A few years after my dissertation ordeal, Julie and I decided to invite him to our wedding. It was our way of letting bygones be bygones and also providing Stanley Kauffmann and his wife someone to talk to. We’d written our own vows, and during the reception afterwards I stopped by their table. “We really liked your vows,” said Stanley and Laura, beaming with all their warm generosity. Sitting beside them was Dick. “I really liked them too,” he said with that little hedge in his voice we all knew so well, “but they were . . . a little long.”

***

Jonathan Kalb is Professor of Theater at Hunter College, CUNY, and the Resident Dramaturg at Theater for a New Audience. The author of five books on theater, he is a two-time winner of The George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism and has worked for more than three decades as a theater scholar and critic, including as a columnist for New York Press, a regular critic for The Village Voice, and a blogger (his TheaterMatters blog is at www.jonathankalb.com). His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Nation, Salon, Salmagundi, The Threepenny Review, The Brooklyn Rail, and many other publications.