by Anton Cebalo

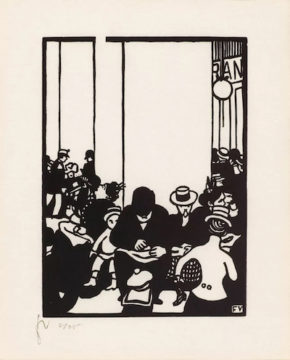

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

This characterization is not mine but taken from Austrian writer Karl Kraus. Kraus believed this environment had to be held responsible for plunging Europe into war. He parodied its excesses in his 1918 play The Last Days of Mankind where he developed his signature montage style. In a time of upheaval, Kraus cut through the noise by repeating its own voice back at it, splicing quotes together into a new interpretation. As he recounted in the play’s preface, “the most improbable deeds reported here actually took place. The most implausible conversations… were spoken verbatim.” Kraus pursued a unique kind of literary realism with the perceptive eye of a documentarian, and in his crosshairs was the newspaper.

Like many writers and artists of the early 20th century—whose perspectives ring so familiar to us today—Kraus sought to dramatize how mass media, particularly the newspaper, was distorting the urban individual’s sense of place. Is it so surprising that writers and artists then, argues critic Lucy Sante, “took such pleasure in shredding it”? After all, the stakes were dire.

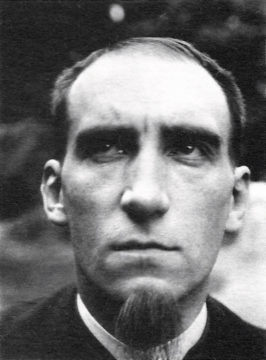

I have been reading Sante’s translation of one such “shredder”: Félix Fénéon. He is an individual who remained largely unknown during his life, but played an outsized role in modernism and early 20th-century literature. Fénéon found himself close to the heart of this media whirlwind I am describing, writing anonymously for the French newspaper Le Matin in 1906. But rather than get caught up in its bluster, he instead opted for an approach that was unique in its candor, simplicity, and intended speed of consumption.

In just a few lines each, Fénéon reported on over a thousand real-life stories in 1906 that sought to show the senselessness of everyday life then. They were printed in snippets as a column, tinged with wit and sometimes even humor. They were written like readymades, as if winking at the reader to say: ‘sadly, this is how things are, take it as you will.’

His stories give us a panorama of unrest and crime in France in 1906—from murders to political corruption to labor agitation and more. Here are a few of them:

Strikers in Ronchamp, Haute-Saône, threw in the river a worker who insisted on continuing his labor.

Delalande’s tender feelings for his maid were such that he killed his wife with a pitchfork. The Rennes assizes sentenced him to death.

Instead of 175,000 francs in the coffers deposited with the tax collector at Sousse, there was nothing.

“If my candidate loses, I will kill myself,” M. Bellavoine of Fresquienne, Seiene-Inférieure, had declared. He killed himself.

The French ditch-diggers of Florac have protested, sometimes with their knives, against the amount of Spanish spoken on their work sites.

The Blonquets stank of drink. A saloonkeeper in Saint-Maur dared refuse them service. They slew him with an indignant dagger.

While thundering for the Republic, a 300-year-old cannon exploded in Chatou, but no one was hurt.

When these stories and many more are read together in a single sitting, it is easy to get overwhelmed by the maladies that plagued France that year. Each snippet is a story unto itself, letting the reader’s mind wander on the details of what took place.

During his life, Fénéon refused to publish all these stories as one book. In fact, he was only revealed to be the author much later in the 1940s. It was finally compiled into an English-translated collection in 2007 by Lucy Sante titled Novels in Three Lines. Its influence in 1906, however, must have been widespread. At the time, Le Matin was one of the big four daily French newspapers with a staff of over 150 journalists. Fénéon would also go on to commission the first French translation of James Joyce’s writing.

One cannot help but relate Fénéon’s style to our short-form way of communicating nowadays, be it a tweet or even a flash fiction story. In a time of print media’s excesses, he “shredded the newspaper.” Given the comparable whirlwind of today’s infosphere, Fénéon, and in his own way Kraus as well, are worth revisiting in how they approached realism sincerely in a time of great upheavel.