by Nils Peterson

At my senior center we have a Shakespeare class led by marvelous young woman, actor, playwright, professional clown. Her main method is to assign us parts and have us read the text out loud. I taught Shakespeare for a bunch of years and did some of this. But this class makes me wish I had done more of having students read out loud. I kept most of the good lines for myself. Selfish. Speaking well-ordered words is one of the great physical pleasures. Yes, physical pleasure. The body responds to good words in the right order (when you say them out loud with appropriate energy) in the way it does to a sip of good wine at evening,

We’ve been doing A Midsummer Night’s Dream and I got the part of Bottom. Here’s what I got a chance to read and rediscover in the reading:

Bottom: When my cue comes, call me, and I will answer. My next is “Most fair Pyramus.” Heigh-ho! Peter Quince? Flute the bellows-mender? Snout the tinker? Starveling? God’s my life, stol’n hence, and left me asleep?

I have had a most rare vision. I have had a dream—past the wit of man to say what dream it was. Man is but an ass if he go about to expound this dream. Methought I was—there is no man can tell what. Methought I was, and methought I had—but man is but a patched fool if he will offer to say what methought I had. The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man’s hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report what my dream was. I will get Peter Quince to write a ballad of this dream. It shall be called “Bottom’s Dream” because it hath no bottom. And I will sing it in the latter end of a play before the duke. Peradventure, to make it the more gracious, I shall sing it at her death.

I had thought to call this piece “The Poetry of Of Incoherence,” but when I thought about it, that title is exactly wrong. Bottom is the most coherent of poets. What is the poet’s job but to find language to explain and share his experience. At this, Bottom is wonderfully successful. His experience is – to be loved by the queen of fairies while wearing an ass’s head. I know enough about wearing an ass’s head in romance to have the publisher of my first book of poems insist that the name of it be The Comedy of Desire. Read more »

We have slid almost imperceptibly and, to be honest, gratefully, into a world that offers to think, plan, and decide on our behalf. Calendars propose our meetings; feeds anticipate our moods; large language models can summarize our desires before we’ve fully articulated them. Agency is the human capacity to initiate, to be the author of one’s actions rather than their stenographer. The age of AI is forcing us to answer a peculiar question: what forms of life still require us to begin something, rather than merely to confirm it? The best answer I’ve been able to come up with is that we preserve agency by carving out zones of what the philosopher

We have slid almost imperceptibly and, to be honest, gratefully, into a world that offers to think, plan, and decide on our behalf. Calendars propose our meetings; feeds anticipate our moods; large language models can summarize our desires before we’ve fully articulated them. Agency is the human capacity to initiate, to be the author of one’s actions rather than their stenographer. The age of AI is forcing us to answer a peculiar question: what forms of life still require us to begin something, rather than merely to confirm it? The best answer I’ve been able to come up with is that we preserve agency by carving out zones of what the philosopher

When promoting her new book in September, Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett stated in an interview as quoted in Politico : “I think the Constitution is alive and well.” She went on – “I don’t know what a constitutional crisis would look like. I think that our country remains committed to the rule of law. I think we have functioning courts.”

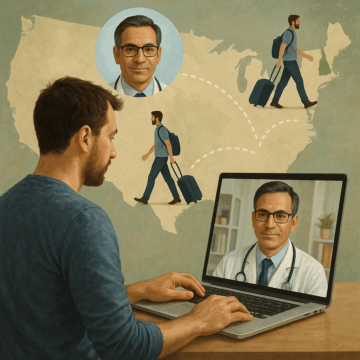

When promoting her new book in September, Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett stated in an interview as quoted in Politico : “I think the Constitution is alive and well.” She went on – “I don’t know what a constitutional crisis would look like. I think that our country remains committed to the rule of law. I think we have functioning courts.” During covid, amid the maelstrom that was American healthcare, a miracle happened. State medical boards suspended their cross-state licensure restrictions.

During covid, amid the maelstrom that was American healthcare, a miracle happened. State medical boards suspended their cross-state licensure restrictions.

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting.

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting. The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random.

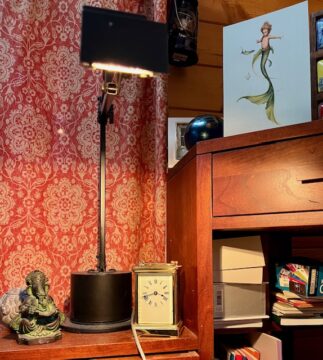

The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random. Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024.

Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024. In a previous essay,

In a previous essay,

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

Isn’t it time we talk about you?