Sughra Raza. Let Me Just Absorb Today.

Sughra Raza. Let Me Just Absorb Today.

Digital photograph, October 2023.

Sughra Raza. Let Me Just Absorb Today.

Sughra Raza. Let Me Just Absorb Today.

Digital photograph, October 2023.

by Chris Horner

Death is not an event in life: we do not live to experience death —Wittgenstein

The anaesthetic from which none come round —Phillip Larkin

What can we do with the thought of death? Nothing can be done about death: you, me, everyone will die. Thinking can’t remove the fact. But the thought of death is another matter. We live with it; we get accustomed to it; we put it out of mind.

Not always of course: that epicurean advice meant to comfort us, that ‘where death is, I am not, and where I am death is not’, has its limits, particularly when we wake in the night. So does the admonition that since we don’t grieve for the aeons in the past when we did not exist, we should not mind not existing in the future. For that is what we fear: no future. We are creatures in time, forever projecting ourselves forward, and so the future we might miss weighs with us more than any past we never had. It’s another reason for dismissing the irritating injunction to live every day as if it were one’s last. We can’t do that: we need to know there will be a tomorrow.

Still, we make a pretty good fist of it on a daily basis. It’s as if the knowledge we have can be safely tucked away and disavowed: ‘I know very well how things are…but still…’ But one day, perhaps not too far in the future, we will cease to exist, be erased, vanish forever. For that is what death is, however we dress it with phrases like ‘passing on’. And we – me, you -are only one diagnosis away from that becoming imminent. Closer every day, comes that unimaginable end. Is it like going into a deep dreamless sleep under an anaesthetic and never waking? I hope so. There are lots of bad ways to die but that seems about the best to be wished for. Read more »

by Ed Simon

Demonstrating the utility of a critical practice that’s sometimes obscured more than its venerable history would warrant, my 3 Quarks Daily column will be partially devoted to the practice of traditional close readings of poems, passages, dialogue, and even art. If you’re interested in seeing close readings on particular works of literature or pop culture, please email me at [email protected]

There is no genuinely effective lyric poem unless there is a line which lodges itself in the brain like a bullet. Often – though not always – these lines are the first in a poem, the better to abruptly propel the reader into the lyric. William Wordsworth’s “I wandered lonely as a cloud,” Walt Whitman’s “I celebrate myself, and sing myself,” or Langston Hughes’ “I’ve known rivers.” For example, John Donne and Emily Dickinson are sterling architects of not just the memorable turn-of-phrase, but the radiant introductory line as well. Think “Batter my heart, three-person’d God” or “I heard a Fly buzz – when I died.”

There is no genuinely effective lyric poem unless there is a line which lodges itself in the brain like a bullet. Often – though not always – these lines are the first in a poem, the better to abruptly propel the reader into the lyric. William Wordsworth’s “I wandered lonely as a cloud,” Walt Whitman’s “I celebrate myself, and sing myself,” or Langston Hughes’ “I’ve known rivers.” For example, John Donne and Emily Dickinson are sterling architects of not just the memorable turn-of-phrase, but the radiant introductory line as well. Think “Batter my heart, three-person’d God” or “I heard a Fly buzz – when I died.”

While memorizing poems in their entirety was a common pedagogical exercise at all levels of education until around a century ago, today works remain pressed in the commonplace-book of-the-mind because of a deftly memorable line, a phrase which announces itself like the hook of a pop song. With some irony, contemporary poetry is sometimes maligned by more conservative critics as having a deficit of iconic lines, where the language itself submerges into an undifferentiated mush of abstract nouns and erratically enjambed lines, experimental precociousness and pretentious obscurantism.

Presumably every period of literary history is deluged with bad poetry so that there is a bias towards that which survives, giving a shining glean to previous centuries which they may not entirely deserve. After all, not every poet in the English Renaissance was the equivalent of Shakespeare; most were as if Giles Fletcher or Barnaby Googe. Still, many readers would perhaps find it difficult to name a poetic turn-of-phrase as memorable as those written by Wordsworth, Whitman, or Hughes, not to mention Donne and Dickinson. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Claire Chambers

I have already written columns for 3 Quarks Daily about starting Hindi language-learning early in the Covid-19 pandemic, continuing to intermediate level as things opened up, and then learning Urdu alongside Hindi once Covid became less of a problem.

However, as is suggested by the post-2020 timestamp of my linguistic odyssey, I am internet ki bachi, a child of the internet. At least at the beginning, I was confined to my house using apps and working with online language tutors during successive lockdowns. As a consequence, I started to become passable in reading, listening, speaking, and writing on my keyboard with the help of a plug-in – but I could not write by hand.

In the final instalment of my previous trilogy, the blog post concerning Urdu, I discussed my hesitancy about handwriting. Finding myself reasonably proficient in constructing emails and short documents on the computer, learning Urdu calligraphy seemed unnecessarily burdensome on my mental capacity. There’s no familial need for me to produce handwritten notes, so I thought this competence wasn’t worth cultivating.

However, Leanne Ogasawara in particular encouraged me to think again. Read more »

by Thomas Wilk and Steven Gimbel

Last month’s open mic night at New College of Florida revealed more than just the comedic ineptitude of its administrators; it exposed the underbelly of a culture clash at the heart of the academic institution. Amidst the cultural war that has engulfed New College, following a takeover by figures appointed by Governor Ron DeSantis, the event was meant to be a light-hearted affair. Instead, it turned into a public spectacle with calls for a dean’s ouster and New College claiming a victory over cancel culture.

Hosted as part of a comedy course, the night featured a routine by Dean of Students David Rancourt that included jokes about a 7-year old boy exposing himself to a girl at the bus stop, violation by a drill sergeant’s baton, and a forced choice between death and “bunga bunga.” The jokes elicited a mix of reactions from the audience. Even New College President Richard Corcoran, who followed Rancourt’s performance, noted the abundance of gay jokes in the set. Corcoran jokingly called Rancourt his “former” dean of students, but, after his homophobic routine, some in the community wish that it wasn’t a joke.

In response to outrage from students and the media, the university gave a statement to The Sarasota Herald-Tribune: “Cancel culture is over at New College. Comedy is a work of art, one that is reliant on our society’s tenets of free speech and free expression. New College supports its students, faculty and staff’s right to participate in artistic endeavors like a comedy performance, or any other civil exercising of free speech and free expression.”

The College is making a common mistake about the ethics of humor. We’d know because we wrote the book on it. The mistake is to think that just because an act is intended to be humorous it must be beyond the scope of moral judgment. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

In a previous post, I began to articulate a conception of gastronomic pleasure loosely based on Aristotle’s view that pleasure is the natural culmination of unimpeded activity. I make use of such an ancient theory because it strikes me as true that when we exercise fundamental human capacities, and that activity proceeds without impediments or obstacles, we experience pleasure. When we don’t get pleasure from activities that engage basic human capacities, it’s because we’re not very good at them or some obstacle to completion was put in our way.

In a previous post, I began to articulate a conception of gastronomic pleasure loosely based on Aristotle’s view that pleasure is the natural culmination of unimpeded activity. I make use of such an ancient theory because it strikes me as true that when we exercise fundamental human capacities, and that activity proceeds without impediments or obstacles, we experience pleasure. When we don’t get pleasure from activities that engage basic human capacities, it’s because we’re not very good at them or some obstacle to completion was put in our way.

Eating, and its component activity tasting, is one such exercise of basic capacities that naturally aims at pleasure when the food is good, the company is right, and one’s sensory mechanisms are functioning properly. Tasting involves the basic skill of pattern recognition. When we eat, we build memory images of what various foods taste like and whether we like them or not. When the flavor/texture patterns in the food we are eating match, without impediment, the memory image of that food (which include hedonic responses), we experience pleasure.

One virtue of this conception of taste is that it accommodates a central feature of our enjoyment of food—familiarity is an important value. We are naturally reticent about taking something into our bodies that might be unpleasant or dangerous. Thus, we experience enjoyment when a present stimulus conforms to the familiar hedonic patterns of past experience. But of course, that memory image of what food should taste like is constantly being updated. We learn to taste new foods if only to avoid boredom since our sensory mechanisms are designed to experience repeated stimuli less intensely. Read more »

by Richard Farr

At first, the countless violations of the law by our new rulers still caused a degree of disquiet. But among the incomprehensible features of those months, my father later recalled, was the fact that soon life went on as if such crimes were the most natural thing in the world. —Joachim Fest, Not I – Berlin, early 1930s

[Y]ou have clearly proved, that ignorance, idleness, and vice, are the proper ingredients for qualifying a legislator; that laws are best explained, interpreted, and applied, by those whose interest and abilities lie in perverting, confounding, and eluding them. I observe among you some lines of an institution, which, in its original, might have been tolerable, but these half erased, and the rest wholly blurred and blotted by corruptions. —Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels, Book II, Chapter VI

The hero of a David Lodge novel says that you don’t know, when you make love for the last time, that you are making love for the last time. Voting is like that. —Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny

Sometimes it’s hard to stay on top of things. While trying to rank-order Nuclear War Over Taiwan, Deforestation in the Amazon, Child Slavery Linked to my own Spending Habits, The Latest Data from the Thwaites Glacier, and What’s Being Done Right Now to the Uighurs the Rohingya the Palestinians the Hazara the Yazidis the Kurds and the Tigrayans, I keep being distracted by trivia, like How Irritated I am to Have Received Yet Another Cloyingly Chummy Fund-Raising Email from the Biden-Harris Campaign.

Sometimes you have to put Now aside and get the cool perspective of ancient sources. So this week I dug around in my shelves and dusted off a book from a distant era. Written by Al Gore, and entitled The Assault on Reason, it’s an eyewitness account of the decline of more or less everything back when the American throne was occupied by the Kennebunkport Dauphin, George II.

Preoccupied with our current traumas, how quickly we forget! Gore is not a neutral observer, but his account is stolidly factual. And the fact is, George II’s reign at the great White Palace in Washington was astonishingly awful. Vandalizing, reckless, arrogant and ignorant; cruel and authoritarian; chaotic and incompetent beyond all previous measure; contemptuous of the law, of democracy, of transparency, of innocent life, of any “decent respect to the opinions of mankind.” In sum, what strikes the modern reader most forcibly perhaps is that the era, half lost in the mists of history, was so strikingly Trumpian. Read more »

—Narragansett Bay —1960, first time out

We part from pier

slow as disengaging lovers

one landlocked, the other a

floater who won’t be kept at bay

The diminishing dock slides back,

its bollards and planks deploy

to some other place not here

—to a distancing otherworld

The tether breaks

as stern-first we pass the

channel buoy

Quarter back, the OD says.

Quarter back, aye sir,

and we slip away

Steer two one zero, half ahead.

Two one zero, half ahead, aye sir

and we slow-slide down

the gleaming bay

The sun’s so bright it indicates

a tern on the roof of a big estate

a half mile away atop its

long lawn hill off the starboard bow

which slopes down clear

through the wind-wove air

to a point where jades meet blues

……… —which passes now as we part the sea while

making way

Further south the sea’s first chops

begin to unsettle our sheltered

adolescent cruise

Near the harbor mouth all decks

rise then make their first

supplicating bows to whatever

god it is who intervenes

to call-off wrecks

…… —we’re juggled gently first in

Neptune’s law as

pitches rolls & heaves

meet yaws

Grey diesel billows from our raked stacks

Halyards snap against the mast’s steel

Gulls abundantly rise & reel

over the white chaos of our wake’s track

Sunlight splinters

into rippled trillions

upon each breaker’s

sequined breast

before it folds

in a white rush, falling

to the soul percussion

of our bow-wave’s

shush

…………. shush

……………………

by Jim Culleny

November, 2009

by Mike Bendzela

We never travel, mainly because working a farm is a career, even a small one like ours, and also because my spouse’s Type 1 diabetes is better managed in a sedentary, predictable existence. I realized in marriage that I would never become “worldly” and didn’t care. I would have to learn whatever I could about the world on this “postage stamp of soil” (1), in William Faulkner’s memorable phrase. This existence has certainly turned us into “foodies” (scare quotes indicating how much I detest the term), even bad-ass foodies in our case, foodies such as our grandparents were. No, strike that–our great grandparents. How many people can say they grow their own stew?

During my twenties and thirties, when we first embarked on this course of Do It Yourself food production, I aspired to be “Green,” “Sustainable,” and “Self-sufficient”–even “Organic”! These are lofty ideals that died directly during their attempted implementation. All these decades later, I’ve settled for home food production and preservation that is cheap, fun, delicious, and humane. Much of it now depends on one big green secret ingredient of farming that I shall reveal at the end. Read more »

by Andrea Scrima

In November 2023, in an essay for the German national newspaper die taz, I wrote that Germany’s Jews were once again afraid for their lives. It was—and is—a shameful state of affairs, considering that the country has invested heavily in coming to terms with its fascist past and has made anti-antisemitism and the unconditional support of Israel part of its “Staatsräson,” or national interest—or, as others have come to define it, the reason for the country’s very existence. The Jews I’m referring to here, however, were not reacting to a widely deplored lack of empathy following the brutal attacks of October 7. In an open letter initiated by award-winning American journalist Ben Mauk and others, more than 100 Jewish writers, journalists, scientists, and artists living in Germany described a political climate where any form of compassion with Palestinian civilians was (and continues to be) equated with support for Hamas and criminalized. Assaults on the democratic right to dissent in peaceful demonstrations; cancellations of publications, fellowships, professorships, and awards; police brutality against the country’s immigrant population, liberal-minded Jews, and other protesting citizens—the effects have been widely documented, but what matters most now is now: the fact that the German press is still, four months later, nearly monovocal in its support of Israel and that over 28,000 civilians, two-thirds of them women and children, have died. Read more »

In November 2023, in an essay for the German national newspaper die taz, I wrote that Germany’s Jews were once again afraid for their lives. It was—and is—a shameful state of affairs, considering that the country has invested heavily in coming to terms with its fascist past and has made anti-antisemitism and the unconditional support of Israel part of its “Staatsräson,” or national interest—or, as others have come to define it, the reason for the country’s very existence. The Jews I’m referring to here, however, were not reacting to a widely deplored lack of empathy following the brutal attacks of October 7. In an open letter initiated by award-winning American journalist Ben Mauk and others, more than 100 Jewish writers, journalists, scientists, and artists living in Germany described a political climate where any form of compassion with Palestinian civilians was (and continues to be) equated with support for Hamas and criminalized. Assaults on the democratic right to dissent in peaceful demonstrations; cancellations of publications, fellowships, professorships, and awards; police brutality against the country’s immigrant population, liberal-minded Jews, and other protesting citizens—the effects have been widely documented, but what matters most now is now: the fact that the German press is still, four months later, nearly monovocal in its support of Israel and that over 28,000 civilians, two-thirds of them women and children, have died. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Mark Harvey

In fiction, there is one story that never gets old: the good man or good woman who is imprisoned or abused, but through strength of character and the force of justice retakes their rightful place in the world. It can be the story of a woman violated by a man or degraded by her envious sisters, a giant of a man lashed down by Lilliputians, a patriot wrongly accused of a crime he didn’t commit or an entire town poisoned by the effluence of a shameless company.

What we love about these stories is the painful sense of injustice followed by a courageous walk to redemption. The dirtier the crime against our hero, the more delicious his or her comeback.

America is deep in the midst of this story. What we love about this country—its possibility to reinvent itself, its original aspiring words about freedom and equality, its grand universities, its thousands of life-changing inventions, its artists and scientists—is in the midst of being degraded and defiled by a bunch of craven, shrill, fake patriots. They’re called MAGATS.

Like many Americans, I tried hard to understand their complaints about the world after Donald Trump got elected in 2016. I read books and articles about how America’s rural states were ignored, about how the flyover states were being left behind, and about how the coastal elites were conspiring to create socialism under a deep state. I’m a bit of an empath so I really tried to walk in the MAGAT moccasins.

I took consideration of the fact that it’s really hard, if not impossible, to lead the old American life of raising a family on one income. I took consideration of the increasing disparities of income between the bottom quintile and the top one percent. Some of the complaints are legitimate, but MAGAT politicians show little interest in alleviating those things and mostly bring forth legislation that makes things worse. Read more »

— on receiving his first hand-written letter in London

by Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938)

Create your own place in the world of love

New time new morning new evening

Listen to the divine within you

Like a hawk searching for live prey

Learn the language of a rose — Inshallah —

For its silence veils Nature’s secret

Shun glazed pottery made in the West

Mold your own cup using India’s clay

Harvest my ghazals like grapes

Ferment them to make sacred wine

Renounce the material

Be like me — a Sufi

***

Transcreated from the original Urdu by Rafiq Kathwari.

by David J. Lobina

by David J. Lobina

Well, first post of the year, and a new-year-resolution unkept. Unsurprising, really.

In my last entry of 2023, I drew attention to the various series of posts I have written at 3 Quarks Daily since 2021, many of which did not proceed in order, creating a bit of confusion along the way. Indeed, the last post of the year was supposed to be the final section of a two-parter, but instead I wrote about how I intended to organise my writing better in 2024. What’s more, I promised I would start 2024 with the anticipated second part of my take on why Machine Learning (ML) does not model or exhibit human intelligence, and yet in my first post of 2024 I published a piece on the psychological study of inner speech (or the interior monologue, as is known in literature), a fascinating topic in its own right, though I am not sure it got much traction, but it really has little to do with ML.

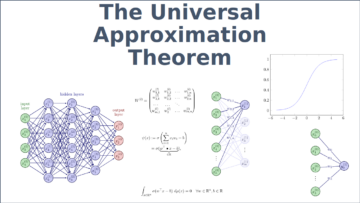

In my last substantial post of 2023, then, I set up an approach to discuss the supposedly human-like abilities of contemporary Artificial Intelligence (AI [sic]™, as I like to put it), and I now intend to follow up on it and complete the series. It is an approach I have employed when discussing AI before, and to good effect: first I provide a proper characterisation of a specific property of human cognition – in the past, I concentrated on natural language, given all the buzz around large language models; this time around was the turn of thought and thinking abilities – and then I show how AI – actually, ML models – don’t learn or exhibit mastery of such a property of cognition, in any shape or form. Read more »

by Carol A Westbrook

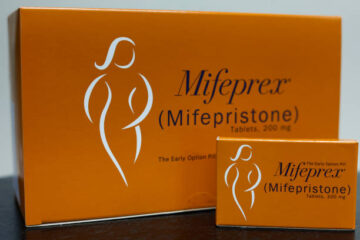

The Supreme Court is poised to make another landmark decision this year, when it determines if it will uphold a Texas Federal court’s ruling that invalidates the FDA’s (U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s) updated labeling of the abortion pill mifepristone (pronounced mi-ˈfe-pri’-stōn) , brand name Mifeprex (Fig 1). Not only will this ruling have a significant impact on abortions in the US, it will also determine whether the Supreme Court (Fig 2) has the power to modify or nullify an FDA ruling. But before we delve any further into this debate, let’s review the action of this drug on the biology of the female reproductive system.

In the early part of a woman’s monthly cycle, her levels of the hormone progesterone rise, and this causes the lining of the uterus to thicken and increases its blood supply, converting it into a state that can support a fetus. After unprotected sex, sperm are deposited in the vagina, and they begin to travel up the fallopian tubes; at the same time, an egg is released from the ovary and travels down the fallopian tube. (Fig 3) When sperm and egg unite, conception occurs. Interestingly, the date of conception does not mark the start of the pregnancy; pregnancy is actually counted from the beginning of a woman’s monthly cycle, two weeks prior to conception. The total length of a pregnancy is usually 40 weeks, or 9 months. Read more »

by Barry Goldman

Reading about corporate greed and depredation over the past f ew years, I keep getting stuck on the same question: Don’t these people have grandchildren? How can corporate decision-makers spend their days actively working to destroy the environment, pollute the water, kill off the animals, melt the glaciers, and incinerate the biosphere? Even if what they care about the most is making more money no matter how much money they already have, don’t they care at all about the world they’re leaving for their kids?

ew years, I keep getting stuck on the same question: Don’t these people have grandchildren? How can corporate decision-makers spend their days actively working to destroy the environment, pollute the water, kill off the animals, melt the glaciers, and incinerate the biosphere? Even if what they care about the most is making more money no matter how much money they already have, don’t they care at all about the world they’re leaving for their kids?

I’ve arrived at a theory. But first I need to back up a few steps.

Readers of 3QD may be familiar with the brain fungus that causes “zombie ants” to leave the safety of the forest floor and climb up the stalks of plants to die. Or the parasite that causes mice to lose their fear of cats. In both cases, the parasite has evolved to hijack the brain of the host and cause it to behave in ways that are suicidal to the host but beneficial to the parasite. The behaviors the parasite causes are often exquisitely complex and particular. It seems impossible that something as primitive as a fungus could be the explanation. But evolution has come up with lots of similar strategies. She is very clever. She doesn’t have a sense of fair play or sportsmanship. If a behavior increases the chances of getting the genes of one generation reproduced in the next, it succeeds. Nothing else matters. And she has lots and lots of time to experiment.

So that’s the first idea we need – the fungus that hijacks the brain of one species to improve the reproductive success of another.

Then we need the idea of cultural evolution. Human beings don’t have to wait for genetic evolution. We have evolved the ability to get information from one generation to the next without having to wait for it first to be encoded in the DNA. We don’t have to start from scratch with each generation, and we don’t have to proceed by trial and error. We have culture, language, and traditional practices. Read more »