by Ed Simon

In Renaissance Europe, a Wunderkammer was literally a “Wonder Cabinet,” that is a collection of fascinating objects, be they rare gems and minerals, resplendent feathers, ancient artifacts, exquisite fossils. Forerunners to the modern museum, a Wunderkammer didn’t claim comprehensiveness, but it rather served to suggest the multiplicity of our existence on this earth, the nature of possibility. Wunderkammers developed alongside that literary form which Michelle de Montaigne called “essays,” literally an “attempt.” Essays, like Wunderkammers, at their most potent are also not comprehensive; rather their purposes is to experiment, to riff, to play. In that spirt, half of my columns at 3QuarksDaily will be dedicated to what I call a “Word Cabinet,” a room dedicated to literature, neither as theory nor even as reading, but to do what both wonder cabinets and essays do, and that is to hopefully provide intimations of possibility. All essays will take the form of “On X and Literature,” where the algebraic cipher indicates some broad, general subject (fire and labyrinths, trees and infinity, etc.). As always, feel free to suggest topics.

* * *

Behind the gleaming, modernist, smooth sandstone façade of Edinburgh’s National Museum of Scotland, a temple to all things Hibernian from the Covenanters to the Jacobite Rebellion, the Highland Clearances to James Watt’s steam-engine, there is a small thirteenth-century walrus tusk ivory carving of a Medieval Nordic soldier. Discovered in a simple stone ossuary buried in a sand dune on the foggy, rain-lashed Bay of Uig on the Outer Hebridean Isle of Lewis in 1831, the little sculpture is just a bit over an inch tall, yet it’s easy to make out the distinctive Scandinavian designs on his pointed helmet, his comical bulging eyes, and his teeth over the top of the shield that he clutches and bites. His is clearly a pose of frenzied, martial wrath. A berserker – the feared caste of Viking warriors who in an enraged fugue state (possibly aided by hallucinogens) terrorized people from Novgorod to Newfoundland, including the Scotts who lived on Lewis where this small figurine would be entombed for six centuries, alongside ninety two other pieces. Not just berserkers, but a mitered bishop of the recently converted Norseman; a tired looking queen with her eyes wide, resting her face upon her balm; a bearded, wise old king.

The berserker isn’t just a tiny statue of a Norse combatant, he’s a warder; what is more commonly known as a rook. This tiny berserker was a chess piece, who even nine centuries ago had the responsibility of charting that distinctive L-shaped course across checkered boards. From India into Persia, than the Arabic world into Europe, chess had already been played for half-a-millennia by the time whatever Norse craftsman took chisel and scorper to a walrus tusk. The rules would be recognizable to contemporary players, though the sterling craftsmanship of the Isle of Lewis chessman – with enough pieces to constitute three complete sets – is rather different than the boring black-and-white pieces used by players today, whether the prodigies competing against paying tourists in view of Washington Square Park’s triumphal arch or the celebrated 1972 match in Reykjavik between Fischer and Spassky. Read more »

No matter where you go, Aristotle believes, the rich will be few and the poor many. Yet, to be an oligarch means more than to simply be part of the few, it means to govern as rich. Oligarchs claim political power precisely because of their wealth.

No matter where you go, Aristotle believes, the rich will be few and the poor many. Yet, to be an oligarch means more than to simply be part of the few, it means to govern as rich. Oligarchs claim political power precisely because of their wealth.

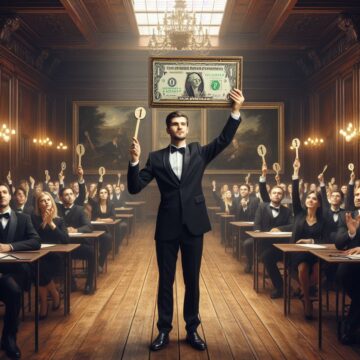

An abstract paradox discussed by Yale economist Martin Shubik has a logical skeleton that can, perhaps surprisingly, be shrouded in human flesh in various ways. First Shubik’s seductive theoretical game: We imagine an auctioneer with plans to auction off a dollar bill subject to a rule that bidders must adhere to. As would be the case in any standard auction, the dollar goes to the highest bidder, but in this case the second highest bidder must pay his or her last bid as well. That is, the auction is not a zero-sum game. Assuming the minimum bid is a nickel, the bidder who offers 5 cents can profit 95 cents if the no other bidder steps forward.

An abstract paradox discussed by Yale economist Martin Shubik has a logical skeleton that can, perhaps surprisingly, be shrouded in human flesh in various ways. First Shubik’s seductive theoretical game: We imagine an auctioneer with plans to auction off a dollar bill subject to a rule that bidders must adhere to. As would be the case in any standard auction, the dollar goes to the highest bidder, but in this case the second highest bidder must pay his or her last bid as well. That is, the auction is not a zero-sum game. Assuming the minimum bid is a nickel, the bidder who offers 5 cents can profit 95 cents if the no other bidder steps forward.

Vitamins and self-help are part of the same optimistic American psychology that makes some of us believe we can actually learn the guitar in a month and de-clutter homes that resemble 19th-century general stores. I’m not sure I’ve ever helped my poor old self with any of the books and recordings out there promising to turn me into a joyful multi-billionaire and miraculously develop the sex appeal to land a Margot Robbie. But I have read an embarrassing number of books in that category with embarrassingly little to show for it. And I’ve definitely wasted plenty of money on vitamins and supplements that promise the same thing: revolutionary improvement in health, outlook, and clarity of thought.

Vitamins and self-help are part of the same optimistic American psychology that makes some of us believe we can actually learn the guitar in a month and de-clutter homes that resemble 19th-century general stores. I’m not sure I’ve ever helped my poor old self with any of the books and recordings out there promising to turn me into a joyful multi-billionaire and miraculously develop the sex appeal to land a Margot Robbie. But I have read an embarrassing number of books in that category with embarrassingly little to show for it. And I’ve definitely wasted plenty of money on vitamins and supplements that promise the same thing: revolutionary improvement in health, outlook, and clarity of thought. Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-portrait on a Young Douglas Fir, May 3, 2024.

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-portrait on a Young Douglas Fir, May 3, 2024.

There is a meme on the internet that you probably know, the one that goes, “Men will do x instead of going to therapy.” Here are some examples I’ve just found on Twitter: “Men will memorize every spot on earth instead of going to therapy,” “men would rather work 100 hours a week instead of going to therapy,” and “men would literally go to Mars instead of going to therapy.” The meme can also be used ironically to call into question the effectiveness of therapy (“Men will literally solve their problems instead of going to therapy”), but its main use is to mock men for their hobbies, which are seen as coping mechanisms taking the place of therapy (“men will literally join 10 improv teams instead of going to therapy”). The implicit assumption in this formula is that the best way for men to solve whatever existential problems they may have is to go to therapy. I don’t particularly like this meme, and I don’t think therapy is necessarily the best way for a man to solve his problems (although it may be in some cases), but what do I know? I’m setting myself up for this response: “men will write a 2,500-word essay about why you shouldn’t go to therapy instead of going to therapy.” Fair enough. I should specify that I don’t have an issue with therapy itself; instead, I have an issue with a phenomenon I find pervasive in contemporary American culture, which is the assumption that therapy is a sort of magic cure for any ills one may have.

There is a meme on the internet that you probably know, the one that goes, “Men will do x instead of going to therapy.” Here are some examples I’ve just found on Twitter: “Men will memorize every spot on earth instead of going to therapy,” “men would rather work 100 hours a week instead of going to therapy,” and “men would literally go to Mars instead of going to therapy.” The meme can also be used ironically to call into question the effectiveness of therapy (“Men will literally solve their problems instead of going to therapy”), but its main use is to mock men for their hobbies, which are seen as coping mechanisms taking the place of therapy (“men will literally join 10 improv teams instead of going to therapy”). The implicit assumption in this formula is that the best way for men to solve whatever existential problems they may have is to go to therapy. I don’t particularly like this meme, and I don’t think therapy is necessarily the best way for a man to solve his problems (although it may be in some cases), but what do I know? I’m setting myself up for this response: “men will write a 2,500-word essay about why you shouldn’t go to therapy instead of going to therapy.” Fair enough. I should specify that I don’t have an issue with therapy itself; instead, I have an issue with a phenomenon I find pervasive in contemporary American culture, which is the assumption that therapy is a sort of magic cure for any ills one may have.