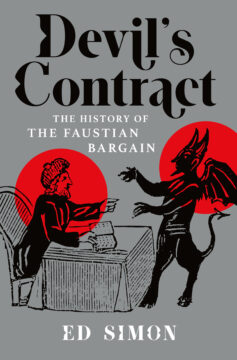

by Ed Simon

Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

Though there are stories about people trading their souls with the devil in exchange for power and knowledge before, it was the English playwright Christopher Marlowe’s 1592 play that firmly entrenched that variety of character in the literary imagination. Incidentally there was a real Johann Faust in the sixteenth century, a German wizard of whom little certain is known, but the similarly dissolute figure of Marlowe was who granted that mysterious figure a variety of immortality. Drawing inspiration from anonymous pamphlets about Faust, Marlowe crafted one of the most chilling tales about how the insatiable thirst for power can lead to damnation when we’re willing to trade our very soul. Notorious at the time, both for the author’s reputation for heresy and sodomy as well as for claims that the script itself was capable of conjuring demons, it was said that Satan himself was in attendance at the premier to evaluate how accurately he’d been depicted. “Hell hath no limits, nor is circumscrib’d,” said the play’s infamous demon Mephistopheles, “where we are is hell,/And where hell is, there must we ever be.” A despairing vision born in Marlowe’s own life, the second most celebrated Elizabethan playwright after Shakespeare who was rightly valorized for the genius of his “mighty line,” ultimately stabbed to death in a tavern fight at the age of 29.

Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Marlowe may have been the one to make the diabolical contract a mainstay of European literature, but it was the nineteenth century German poet and polymath Johann Goethe who elevated the story into the canon of eternal works. A genius who dabbled in everything from botany to anatomy, Goethe is nonetheless most celebrated for his brilliant writings responsible for the inauguration of the passionate and emotional literary movement of Romanticism. His Faust, written in two voluminous parts respectively published in 1790 and 1808, was intended to be a “closet drama,” a type of verse play meant to be read rather than performed. Drawing from the same wellspring of German myth as Marlowe, Goethe nonetheless reinvents the details and purpose of the Faust legend. Fleshing out a love interest for the wizard, Goethe also more importantly reorients the focus of the devilish contract into a wildly expansive philosophical vision, having Faust sell his soul not for power or even knowledge, but rather a very Romantic zeal for unadulterated human experience. Most arrestingly, the Faust of Goethe’s poem finds a salvation denied the magician in Marlowe’s play, though the questions raised about human freedom and depravity along the way remain disturbing, this sense that “Man errs as long as he strives.” Read more »

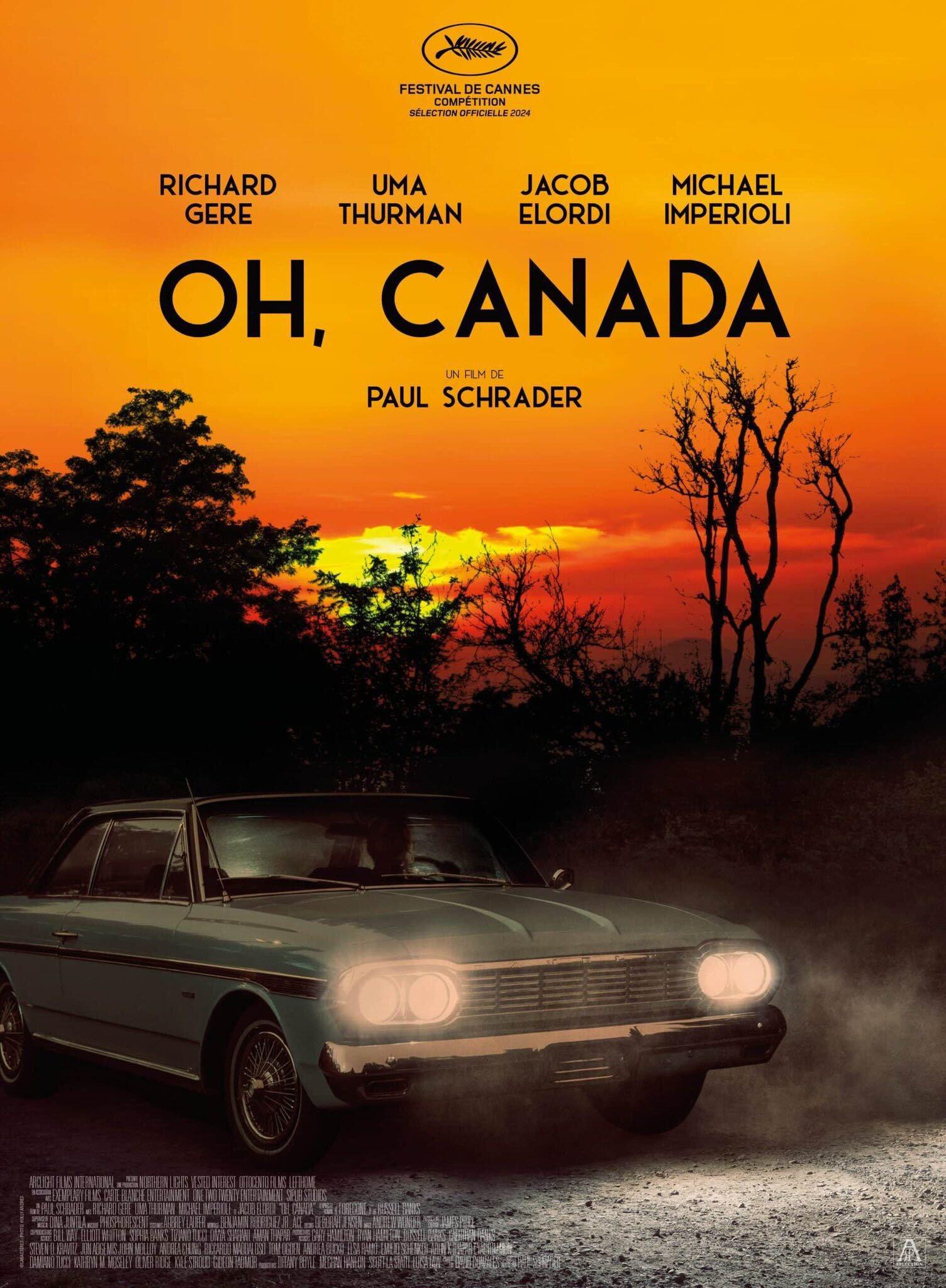

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks.

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks. The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels

The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.

In the 21st century, only two risks matter – climate change and advanced AI. It is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture and get lost in the maelstrom of “news” hitting our screens. There is a plethora of low-level events constantly vying for our attention. As a risk consultant and

In the 21st century, only two risks matter – climate change and advanced AI. It is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture and get lost in the maelstrom of “news” hitting our screens. There is a plethora of low-level events constantly vying for our attention. As a risk consultant and