by Ben Orlin

There is something reassuring about teaching math. On the eve of a pivotal election, as my colleagues in U.S. history grapple with their subject’s urgent and terrible relevance, I can console myself that math is rarely urgent, and (as we tend to teach it) almost never relevant.

Or so it would seem. But math has a guilty secret: its longstanding role in American statecraft.

I’m not referring to math’s technocratic applications, or the pious calls for better STEM education. Rather, math has long inspired our country’s leaders for precisely the same reason that it befuddles our students: its willingness to wrangle with abstraction.

Math is the science of unifying laws. As such, it has served as a model for our messy republic’s perpetual efforts to live up to the “United” in its name.

I scarcely exaggerate when I say that we are the people of the equals sign.

Thomas Jefferson was an avid mathematician. He described calculus as “a delicious luxury,” and trigonometry as “most valuable to every man,” adding, “there is scarcely a day in which he will not resort to it.”

(Sidebar: I spent years teaching trig, and never once heard this sentiment echoed.)

In 1776, when Jefferson penned his famous equation—that all men are created equal—he was not trying to set the U.S. apart. Quite the opposite: the Declaration’s goal, he later wrote, was “to place before mankind the common sense of the subject,” so as to persuade other nations of our cause. Read more »

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on.

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on. A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

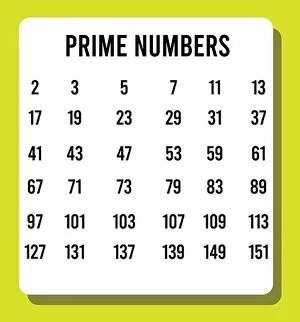

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.