New York City at twilight from the top of the New Museum in July, 2016.

New York City at twilight from the top of the New Museum in July, 2016.

by Nickolas Calabrese

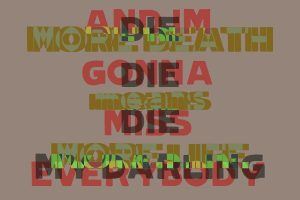

1. “…And I, who timidly hate life, fascinatedly fear death.” Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet.

1. “…And I, who timidly hate life, fascinatedly fear death.” Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet.

2. I didn’t ask to be born, yet I’ve been condemned to death. Early on in Plato’s Phaedra, Socrates declares that it’s the job of the philosopher to prepare for death. Addressing Simmias and Cebes he states, “I am afraid that other people do not realize that the one aim of those who practice philosophy in the proper manner is to practice for dying and death.” There is something vulgarly sunny in the way he suggests it, but it also rings clearly true. What philosophers talk about when they talk about ‘the good life’ is a life not regretted when it comes time to exit it. Theirs is the pursuit of truth and understanding, and our own mortality could not be a more present topic to pursue.

3. Quite a few artists are engaged in a similar investigation. Although theirs is not as pure as the philosophers’, the good ones have a strong tendency to make work that both eviscerates vanity and frames mortality. By its very nature, the subject becomes the object. The countless examples of musicians, artists, poets, etc., examining the finitude of their own lives constitutes a vast list. Those who have spent time producing work in this vein are legion: from Bob Dylan to Future, from John Donne to Amiri Baraka, from Cady Noland to Andy Warhol. It comes as no surprise that one’s own death is an attractive topic. After all it’s something that every person ever has either done or will do in their lives. Death is more common than emotions. Not all people are capable of, say, love, but everyone must die. But what artists try to do with their work is antithetical to what Socrates was defining: artists are trying to cheat death. I’ll say more about this further down. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

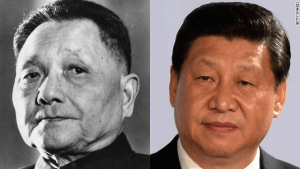

This is the 40th anniversary of the onset of economic ‘reform and opening-up’ (gaige kaifang) in China under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, which eventually led to a dramatic transformation of its economy and global status. It is, however, remarkable that China’s current supreme leader, Xi Jinping, marked the anniversary in a speech in the Great Hall of People in Beijing mainly emphasizing the Party’s pervasive control. It is also remarkable that in recent years this leadership seems to have forsaken Deng’s earlier advice of tao guang yang hui (“keep a low profile”). In the flush of Chinese nationalist glory, Xi explicitly stated in the 19th Party Congress that China has now entered a “new era”, when its model “offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”. Many people both in rich and poor countries seem to be already awe-struck by this model.

This is the 40th anniversary of the onset of economic ‘reform and opening-up’ (gaige kaifang) in China under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, which eventually led to a dramatic transformation of its economy and global status. It is, however, remarkable that China’s current supreme leader, Xi Jinping, marked the anniversary in a speech in the Great Hall of People in Beijing mainly emphasizing the Party’s pervasive control. It is also remarkable that in recent years this leadership seems to have forsaken Deng’s earlier advice of tao guang yang hui (“keep a low profile”). In the flush of Chinese nationalist glory, Xi explicitly stated in the 19th Party Congress that China has now entered a “new era”, when its model “offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”. Many people both in rich and poor countries seem to be already awe-struck by this model.

What are the special characteristics of the Chinese development model? Briefly, it’s a model of essentially capitalist development under authoritarian leadership and purposive governance, with a vertical production structure where basic capital goods are produced in monopoly state-owned enterprises and the much-larger rest of the economy is under private ownership, with a state-guided nationalist industrial policy and finance, with subsidized access to land and credit for state-favored business and repression of labor rights, massive investments in infrastructure funded by a very high national savings rate (particularly on account of large undistributed profits of companies), with rural industrialization in a decentralized framework of jurisdictional competition, and openness to foreign trade and acquisition and learning of foreign technology. It has produced a rapid pace of economic growth over the last three decades and lifted hundreds of millions of people above the poverty line—undoubtedly a spectacular historic feat for any developing country. The recent slowing of the growth rate does not tarnish the long-term shining performance so far.

I have discussed some of these features of Chinese development, particularly in a comparative assessment with Indian development, in my book Awakening Giants, Feet of Clay (Princeton, 2013)—incidentally, I should mention here that when a Chinese translation of this book came out in Beijing, the translator thought it fit or prudential to take out, without my permission, some of the passages in the book that criticized Chinese policy, while those critical of Indian policy remained.

I believe the Chinese governance system is a crucial part of the China development model, and in this article I shall concentrate on its special features, both positive and negative, which tend to be overlooked in the simplistic discussion on authoritarianism vs. democracy that tends to dominate the usual observations on the system. Authoritarianism is neither necessary nor sufficient for some of those special features. In many ways these features undergirding the Chinese polity and economy are quite distinctive, and their roots go long back in history. I shall focus here on the aspects of governance that affect economic development and less on their clearly repressive police-state aspects and gross abuse of basic human rights. Read more »

by Thomas O’Dwyer

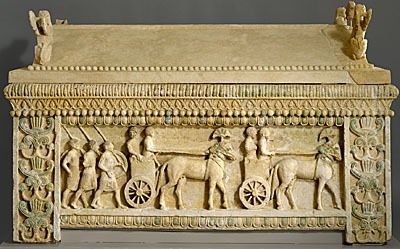

French President Emmanuel Macron has set a very large cat among the pigeons of global antiquities trading and curating. The cat – catalogue – is a report he commissioned in March 2018 and it’s named The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics. It identifies tens of thousands of cultural artifacts looted from Africa in French colonial days that could be repatriated. France’s national syndicate of antique dealers has already howled in protest at the report. In a letter to the culture minister, the Syndicat National des Antiquaires wrote: “The risks of extensions to other geographical areas and periods of history do not seem to have been anticipated.” In a separate statement, the syndicate expressed concern that the proposed repatriations would cover objects from the Americas, Asia, the Mediterranean and European countries.

A debate on Western theft from foreign cultures has been around since the nineteenth century. Only now is it gathering real momentum. It is a controversy which rumbles on in specialist magazines and art sections of various media. It erupts at times into open public rows over the most notorious cases – the theft of the Greek Parthenon Marbles by Britain’s Lord Eglin, for instance. There have been vocal demands from Greece, Egypt, Italy, Thailand and China for the return of treasures stolen by colonial marauders. Moral arguments abound over the sale of art pieces that Hitler’s Nazis plundered from European Jews. Such treasures now are often restored to surviving Jewish family members and their descendants. The moral case is that when buyers pay for art objects in good faith, it does not erase the original crime that makes such transactions possible. It is now being argued that this could apply to the millions of stolen artifacts laid out in the dusty cabinets of the world’s great museums. Read more »

by Jeroen Bouterse

“Am I ever going to use this later?” As a math teacher, I seem to be getting this question about once a month (which is actually less frequently than I would have predicted). It is asked with varying degrees of openness to the idea that a satisfying reply is even conceivable, but almost invariably by students who are probably justified in believing that their tertiary education or future career is going to involve few linear equations indeed.

Rather than trying to conjure up some practical situation in which one might need to solve a fractional equation, I usually suggest that math may be worthwhile even if it turns out you can safely forget the techniques you learned in school. Isn’t this puzzle fun, doesn’t it make for good mental exercise, don’t you feel yourself getting a little bit smarter? Implicitly, I am banking on the idea that math improves your thinking. But what does that mean?

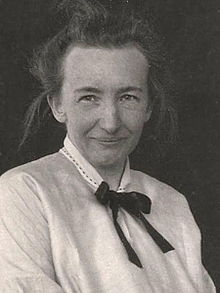

Recently, I stumbled upon a pamphlet from the 1920s that turned out to be both a feast of recognition and a source of further questions. Its author was Tatiana Ehrenfest-Afanassjewa. A Russian mathematician and physicist, Ehrenfest-Afanassjewa spent much of her time teaching mathematics and developing a program of mathematical pedagogy. Having worked in St Petersburg, she moved to the Netherlands in the 1910s when her husband, Paul Ehrenfest, became a professor of physics at Leiden University. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

I wrote the first draft of this post on my typewriter. Like much of my other writing, this piece began as handwritten notes and drafts typed on a nice little portable typewriter, which is a little younger than I am and which I expect to use for the rest of my life.

I wrote the first draft of this post on my typewriter. Like much of my other writing, this piece began as handwritten notes and drafts typed on a nice little portable typewriter, which is a little younger than I am and which I expect to use for the rest of my life.

I first thought about using a typewriter because I wanted fewer distractions when I write. One of the beauties of the typewriter is that it does just one thing. You can’t check your email or anything else; you can’t multitask. You can’t follow any of the myriad paths that the Internet opens up. You can write whatever you want to, but all you can do is write.

Another reason I chose to do some of my work on a typewriter is that the computer has become associated in my mind with various types of paid online work—office jobs that were ultimately tedious, and more recently, my current editing work. These days when I face a piece of text on the computer and have to interact with it (rather than read it), my default attitude is finicky, and I always have an eye to the ways that others will evaluate my work. This makes it harder to move out of editor mode and into writing mode when I’m working on the computer. I thought a typewriter might provide a more friendly environment for writing, especially in the early stages, when ideas are often at their most nebulous and easily scattered, and when I’m most easily discouraged or overwhelmed. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

The traveler comes to a divide. In front of him lies a forest. Behind him lies a deep ravine. He is sure about what he has seen but he isn’t sure what lies ahead. The mostly barren shreds of expectations or the glorious trappings of lands unknown, both are up for grabs in the great casino of life.

The traveler comes to a divide. In front of him lies a forest. Behind him lies a deep ravine. He is sure about what he has seen but he isn’t sure what lies ahead. The mostly barren shreds of expectations or the glorious trappings of lands unknown, both are up for grabs in the great casino of life.

First came the numbers, then the symbols encoding the symbols, then symbols encoding the symbols. A festive smattering of metamaniacal creations from the thicket of conjectures populating the hive mind of creative consciousness. Even Kurt Gödel could not grasp the final import of the generations of ideas his self-consuming monster creation would spawn in the future. It would plough a deep, indestructible furrow through biology and computation. Before and after that it would lay men’s ambitions of conquering knowledge to final rest, like a giant thorn that splits open dreams along their wide central artery.

Code. Growing mountains of self-replicating code. Scattered like gems in the weird and wonderful passage of spacetime, stupefying itself with its endless bifurcations. Engrossed in their celebratory outbursts of draconian superiority, humans hardly noticed it. Bits and bytes wending and winding their way through increasingly Byzantine corridors of power, promise and pleasure. Riding on the backs of great expectations, bellowing their heart out without pondering the implications. What do they expect when they are confronted, finally, with the picture-perfect contours of their creations, when the stagehands have finally taken care of the props and the game is finally on? Shantih, shantih, shantih, I say. Read more »

by Adele A Wilby

Although we know bias and racism exists in most societies, when put into coherent terms in the form of research the impact is stark and exposes just how much a part of life racism is for so many people. Booth and Mohdin’s (The Guardian 2018) article ‘Revealed: the stark evidence of everyday bias in Britain’ setting out the findings of a poll on the levels of negative experience, more often associated with racism, by Black, Asian and minority and ethnic groups in the United Kingdom(UK) does just that. Thus, for example, from amongst its many findings the survey revealed that 43% of those from a minority background had been overlooked for work promotion in the last five years in comparison with only 18% of white people who reported the same experience. Likewise, 38% of people from ethnic minorities said they had been wrongly suspected of shop lifting in the last five years, in comparison with 14% of white people. Significantly, 53% of people from a minority background believed they had been treated differently because of their hair, clothes and appearance, in comparison with 29% of white people. In the work-place also 57% of minorities said they felt they had to work harder to succeed in Britain because of their ethnicity, and 40% said they earned less.

Although we know bias and racism exists in most societies, when put into coherent terms in the form of research the impact is stark and exposes just how much a part of life racism is for so many people. Booth and Mohdin’s (The Guardian 2018) article ‘Revealed: the stark evidence of everyday bias in Britain’ setting out the findings of a poll on the levels of negative experience, more often associated with racism, by Black, Asian and minority and ethnic groups in the United Kingdom(UK) does just that. Thus, for example, from amongst its many findings the survey revealed that 43% of those from a minority background had been overlooked for work promotion in the last five years in comparison with only 18% of white people who reported the same experience. Likewise, 38% of people from ethnic minorities said they had been wrongly suspected of shop lifting in the last five years, in comparison with 14% of white people. Significantly, 53% of people from a minority background believed they had been treated differently because of their hair, clothes and appearance, in comparison with 29% of white people. In the work-place also 57% of minorities said they felt they had to work harder to succeed in Britain because of their ethnicity, and 40% said they earned less.

That racism, and indeed anti-Semitism, should be relegated to the dustbin of history is an aspiration shared by many. Of course, it is doubtful that there has ever been a society where racism has not been present. Nevertheless, that is not an excuse for it to become an acceptable phenomenon; it is a scourge on humanity, and has been the source of barbarity and brutality, cruelty and humiliation amongst fellow human beings. Its perpetual presence also serves to remind us of just how little we have learned from its devastating and harmful impact on peoples and societies throughout history. Thus, the recent research and reports of racism in the UK evoked reflection, and reminded me of my personal experience of racism in the United Kingdom, and how I realised the full weight of the phenomenon after the death of my husband. Read more »

THE VALE OF SAINTS

I drove up the Himalayan foothills

to Baba’s shrine

with my friend Masood

in a tired white Gypsy

with dodgy brakes,

urged on by my 94-year-old

mother at Hebrew Home

The Bronx

who said her father,

a wealthy ring-shawl merchant

patronized by the Maharajah,

had married three times

hoping to produce an heir,

but his wives proved barren.

Perhaps it was him,

Mother said.

Yet, he rode his Tonga

to the foothills, then trekked

to the thatched-roof shrine

where he tied a thread

to carved wooden roses,

prayed for a son.

Faith in Sufi mysticism

defined Islam in Kashmir,

commanding awe & respect

never shock & suspicion. Read more »

by Gabrielle C. Durham

In the immortal words of Prince Rogers Nelson’s party gem from 1982:

In the immortal words of Prince Rogers Nelson’s party gem from 1982:

“But life is just a party, and parties weren’t meant to last . . .

“So tonight I’m gonna party like it’s 1999.”

So much fun stuff happened in 1999: rampant concern about Y2K; the movie “The Matrix” came out; Bill Clinton’s ongoing inability to keep his dick in his pants and subsequent impeachment and acquittal; former pro wrestler Jesse Ventura became governor of Minnesota; U.S. military college The Citadel graduated its first female cadet; the Elian Gonzalez controversy raged in the States; and Cher’s single “Believe” was released.

But do you remember what you said? Do you remember when something made you laugh, not LOL? It was not actually all that long ago, TBH. Back in 1999, reading a text typically meant applying a highlighter, most likely in neon yellow, to the testable information in a book or handout that the teacher assigned. It has a very different meaning from today’s pithier text message. In a score of years, English has changed. Duh, language is always changing; that’s how it stays alive. But if we think about it at all, we think of language change as being in evolutionary terms – something that takes generations, but it actually happens much more quickly. Read more »

by Joshua Wilbur

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.” —Annie Dillard

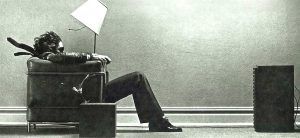

According to a July 2018 report from Nielsen, American adults now spend more than 11 hours a day on average consuming some form of media. The study considered time spent on television, radio, apps on smartphones, apps on tablets, internet on a computer, game consoles, and other devices. The study excluded print formats, such as books, magazines, and newspapers.

Eleven hours per day is a lot of time. Even if we add print formats to the mix—with the implicit judgement that “book hours” are superior to those dedicated to Netflix or Instagram—the fact remains that the majority of our waking lives is spent in engagement with the creations of other people. More than ever before, we are socially-hungry, story-obsessed, entertainment-seeking creatures.

It’s easy enough to decry this state of affairs. Postmodernists on the Left have long cast a critical glance at consumer culture, commodity fetishism, and the struggle between greedy hoarders of capital and passive wage-earners, who, like the singing Prole woman in Orwell’s 1984, are free to amuse themselves to death. In the 1960s, Guy Debord characterized the modern West as a “Society of the Spectacle” in a book of the same name. According to Debord, “All that was once directly lived has become mere representation.” We prefer action shows to real adventure, rom-coms to actual romance, hi-def images to genuine experiences. Will Self, who just months ago wrote an essay called “The Printed Word in Peril” for Harper’s Magazine, described his impressions of Debord’s treatise in a 2013 article for the Guardian: “Rereading The Society of the Spectacle, I was struck yet again […] by Debord’s astonishing prescience – for what other text from the late 1960s so accurately describes the shit we’re still in?”

And yet, for all the well-placed critique, I can’t help but feel that Debord’s picture of people as ideology-drugged spectators reflects our reality in the worst possible light and, in any case, bemoaning it doesn’t get one very far. Read more »

View from my 12th floor hotel room in rainy London in September, 2017.

by Carol A Westbrook

On the first day of creation, God said. “Let there be light,” according to the Bible. In most major religions, God creates day and night, the sun, or light itself on the first day. To the ancients, the sun was God Himself–the Egyptians had Ra, and the Aztecs, Huītzilōpōchtli.There is something divine about light. Even a non-religious person feels a sense of something special when in bright sunlight.

first day. To the ancients, the sun was God Himself–the Egyptians had Ra, and the Aztecs, Huītzilōpōchtli.There is something divine about light. Even a non-religious person feels a sense of something special when in bright sunlight.

Sunlight! We crave it. We open the drapes, we spend time in the sun, we gaze at the sunset, we build stone  monuments to track it. In the dark days of winter we brighten our homes with candles and holiday lights. Winter religious holidays like Christmas and Chanukah emphasize lights and candles to brighten the darkness, while other holidays come during spring, when the days get longer. Many of us feel the need to travel south in

monuments to track it. In the dark days of winter we brighten our homes with candles and holiday lights. Winter religious holidays like Christmas and Chanukah emphasize lights and candles to brighten the darkness, while other holidays come during spring, when the days get longer. Many of us feel the need to travel south in  the dead of winter, to get a few days of bright light and longer days.

the dead of winter, to get a few days of bright light and longer days.

We don’t need to invoke religion to explain our craving for light, we can look to biology. Light–specifically daylight–is a human need, almost as critical as food, air and water. We need the periodicity of daylight to control our bodily processes, in particular those which occur in a diurnal cycle, such as sleeping, waking, meals, drowsy times, body temperature variations, and fertility.

Hormones control this periodicity. These include cortisol, which controls blood sugar and metabolism, and melatonin, a sleep regulator. Read more »

by Christopher Bacas

“Eets beeg place. Millennium Theater. Brighton Beach. You see it. We start seven. Very good band. Leader has gigs coming up. I tell him you coming.”

“Eets beeg place. Millennium Theater. Brighton Beach. You see it. We start seven. Very good band. Leader has gigs coming up. I tell him you coming.”

Ivan gave me specs and I agreed to make it. Lack of guaranteed money, opportunity, entertainment, enlightenment or even a ride home won’t stop a true band kid.

Brighton Beach Station follows Sheepshead Bay. Turning west toward Coney Island, the train grinds into a corner, wheels shrieking. In front: an ocean bends light behind towering beachfront buildings. Beneath the tracks: awnings, Cyrillic signage, overflowing produce bins, foot traffic crisscrossing a wide street.

I arrived early, on a rush hour train. Across the platform, stylish, perfectly coiffed women, teenage to babushka, waited to go to Manhattan. Heading down, many feet vibrated the iron steps, filigreed bars on a 3D xylophone. Soulful Russian ballads and techno crackled from outdoor speakers mounted above cell phone shops and grocers. The Millennium’s unlit marquee appeared high on the left. Below it, a café spread onto the sidewalk. Read more »

by Max Sirak

“Once in while you get shown the light / In the strangest of places if you look at it right.”

The Grateful Dead sing that. It’s a line from Scarlet Begonias that goes through my mind in moments of pleasant surprise. And, as this essay is all about an instance of encountering wonder in an unlikely place, it seems a fitting place to start.

Forgetting how incredible it is to be alive and how good we have it is easy. We swim surrounded in a sea of marvels that previous generations couldn’t have imagined and might’ve called magic. Yet, because this is our everyday and we’re used to living this way, we hardly afford this truth a second thought.

Our near constant confrontation with news to the contrary also works to warp the wonder from our world view. Authoritarian regimes with Populist flares proffer. Climate change and our dependency on toxic energy destroys our planet. Humanitarian crises span our globe. And these are just the first three counterpoints that came to my mind.

I don’t mean to diminish the threats we face. Our current plights are real and important. But, so too is staying afloat. Read more »

by Holly A. Case

There is a nice neighborhood in Istanbul called Kadıköy, which means “village of the kadı,” or “judge.” One might as well call it Kediköy, however: “village of the cat.” There are a lot of stray cats there, as there are throughout the city. Once I saw a poster with a photo of a cat that said “Lost” at the bottom, then a phone number (rather like seeing a sign on the beach with a picture of a shell reading “Lost,” then a phone number). The sign was taped to a utility box on the street. On top of the box was a stray cat, lounging. It looked a lot like the one in the photo.

A few years ago, I met a retired architect who came down to the promenade along the reinforced shoreline every morning to feed the stray cats. “If there is a heaven and hell, which I don’t believe there is, but if there is, I will go to heaven on their prayers,” he told me.

In a different part of the city, my friend Kerim—a tailor—begins his two-hour commute to work at 6 a.m. Six days a week he pets the stray dogs on one side of the highway, then crosses to the other side to catch the bus where he meets a second pack of strays and pets them. Recently he constructed a luxury home for a stray cat who had taken up residence at the bus stop. It’s a cardboard box wrapped in plastic (to keep it dry), with a styrofoam roof (for insulation), a bubble-wrap subfloor (also for insulation), cardboard flooring, and an interior wall-to-wall rag (for extra comfort). He proudly showed me a photo of it with the occupant just visible inside. Read more »

In all cases, the goal is to move past literal life into the imagination

to render the almost—to express the mysterious ambiguity that is. . .

……………………………………………….. —Nicholas Dawidoff, writer

yesterday

I walked our yard

with a grandson

who toddled beside

in a state

almost

of disequilibrium

but he tended

his balance

and stayed upright

and the walk

we walked was

almost

something which would come again

when he’d walk with

his grandson —if his days

were almost

like mine

almost as lucky

restless

reckless

full

fettered

free

almost

happy as a calm

shifty sea

full and vacant as the hole

at the center of a wheel

around which

if it were not hollow

its rim would never spin

and there’d be nothing,

including me

but nada is nothing

we can imagine

or almost

be

Jim Culleny

5/22/17

by Emrys Westacott

Like millions of other people in the US, I often begin the day by listening to ‘Morning Edition,’ the early morning news program on National Public Radio. Sometimes, though, I get so disgusted by the rubbish spewed by the politicians being interviewed, or so infuriated by the flimsiness of the questions put to them, that I just can’t stand it and have to take myself out of earshot. Friday was a case in point.

Like millions of other people in the US, I often begin the day by listening to ‘Morning Edition,’ the early morning news program on National Public Radio. Sometimes, though, I get so disgusted by the rubbish spewed by the politicians being interviewed, or so infuriated by the flimsiness of the questions put to them, that I just can’t stand it and have to take myself out of earshot. Friday was a case in point.

The topic, of course, was the partial shutdown of the federal government. Congressman Gary Palmer, a Republican from Alabama, came on to be interviewed. Here was the first question

“Both sides have to give in any kind of compromise deal… Where should the Republicans and the president be willing to compromise?”

Right there was where I’d had enough. It is simply nonsense that in every negotiation both sides have to compromise, moving toward some sort of shared middle ground. This is not the received wisdom when it comes to dealing with hostage takers. And that is exactly the situation the House of Representatives is currently in. Read more »