by Dwight Furrow

The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As I noted last month, agency in the wine community is dispersed with many independent actors having some influence on wine quality. This dispersed community is held together by conventions and traditions that foster the reproduction of wine styles and maintain quality standards. Most major wine styles are embedded in traditions that go back hundreds of years and are still vibrant today. Although the genetic instability of grapes and their sensitivity to minor changes in weather, soil and topography are agents of change, most of these changes are minor variations within a context of stability. We create new varietals, discover new wine regions, and develop new technologies and methods but these produce minor deviations from a core concept that sometimes seems immune to radical change. There are, after all, only so many ways to ferment grape juice. Red and white still wine, sparkling wine, and fortified wine have been around for centuries and are still the main wine styles on offer. Every wine we drink is a modification of those major themes.

The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As I noted last month, agency in the wine community is dispersed with many independent actors having some influence on wine quality. This dispersed community is held together by conventions and traditions that foster the reproduction of wine styles and maintain quality standards. Most major wine styles are embedded in traditions that go back hundreds of years and are still vibrant today. Although the genetic instability of grapes and their sensitivity to minor changes in weather, soil and topography are agents of change, most of these changes are minor variations within a context of stability. We create new varietals, discover new wine regions, and develop new technologies and methods but these produce minor deviations from a core concept that sometimes seems immune to radical change. There are, after all, only so many ways to ferment grape juice. Red and white still wine, sparkling wine, and fortified wine have been around for centuries and are still the main wine styles on offer. Every wine we drink is a modification of those major themes.

Nevertheless, sometimes wine styles change, often massively. In a community so bound by tradition how does that change take place? One example of a massive change in taste took place in the U.S. in the decades following WWII, where in the course of about twenty years American wine consumers changed their preference from sweet wine to dry. How did such a revolution in taste occur in such a relatively short period of time? Read more »

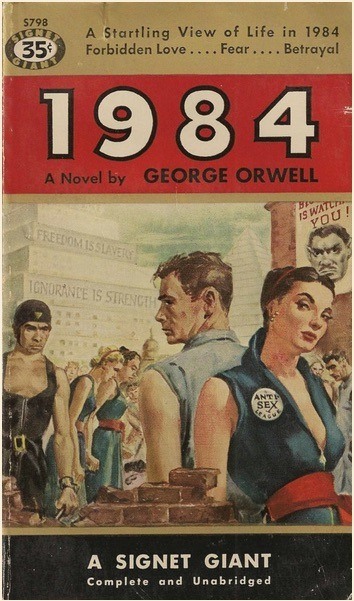

A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with

A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with  In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”