by Dwight Furrow

Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past.

Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past.

This general improvement in wine quality is to be welcomed but I would argue that for wine aesthetics a more important development is the unprecedented diversity in our wine choices. What wine writer Jon on Bonné, recently referred to as “weird wine”—natural wine, orange wine, wine in cans, wine from unfamiliar locations—is an important part of the wine conversation. Wine is now made in every state in the U.S. and most of those states have their own indigenous wine cultures with distinctive varietals and unique terroirs. Throughout the world, emerging new wine regions from Great Britain to China promise to add to the stock of diverse tasting experiences. Wine grapes are increasingly grown in extreme environments—from high in the Andes, to the deserts of the Golan Heights, to the chill lake sides of Canada. Projects such as Vox Vineyards in Kansas City, Bodegas Torres in Spain, and Bonny Doon in Santa Cruz, California are rediscovering lost or ignored varietals while the University of Minnesota develops new varietals that can survive Northern winters. If you’re willing to navigate our spotty distribution system, most of this diversity is widely available. Although the best wines from the storied vineyards of France are now available only to the super wealthy, new generations of wine drinkers are growing tired of the hamster wheel of Cabernet/Chardonnay/Merlot and are seeking something more adventurous.

This focus on variation has not always been an intrinsic part of wine culture. As I described in my column last month, in the early 1990’s the growing wine culture in the U.S. was dominated by trends that would tend to increase homogeneity. Excessive ripeness, a reductionist approach to wine science, overly narrow critical standards, and most importantly rapid growth in the wine industry were poised to transform wine into a standardized commodity like orange juice and milk, serving a function but without much aesthetic appeal.

So what happened? How did we avoid that monotonous landscape of homogeneous juice? Read more »

r a train and someone passed through begging for change. I’ve lived in New York City long enough that I don’t just start taking my wallet out and going through it in crowded public spaces, but beyond that, I don’t have change. I normally don’t carry cash. If I have cash on me its for one of two reasons, either someone has paid me back for something in cash (which in these days of Venmo is increasingly unlikely) or I have a hair or nail appointment where they like their tips in cash. So even if I have cash, it’s bigger bills and certainly no coins. And I’m sure I’m not unusual. I pay for things with credit cards. I pay other people using Apple Pay or Venmo. I mentioned this thought to someone who told me that they had seen someone begging in New York with details of their Venmo account. On the one hand, there seems to be a certain chutzpah to that, after all, if you have a bank account to receive the money in and some kind of smart phone to access it, is your situation as dire as you’re making out? On the other hand, it’s pretty smart. Of course, there are serious privacy issues involved in giving money to a random stranger through an app like Venmo, it’s not private, so I probably wouldn’t do that either, but it’s an interesting idea, if it could be made more anonymous and secure. Apparently, at least in China,

r a train and someone passed through begging for change. I’ve lived in New York City long enough that I don’t just start taking my wallet out and going through it in crowded public spaces, but beyond that, I don’t have change. I normally don’t carry cash. If I have cash on me its for one of two reasons, either someone has paid me back for something in cash (which in these days of Venmo is increasingly unlikely) or I have a hair or nail appointment where they like their tips in cash. So even if I have cash, it’s bigger bills and certainly no coins. And I’m sure I’m not unusual. I pay for things with credit cards. I pay other people using Apple Pay or Venmo. I mentioned this thought to someone who told me that they had seen someone begging in New York with details of their Venmo account. On the one hand, there seems to be a certain chutzpah to that, after all, if you have a bank account to receive the money in and some kind of smart phone to access it, is your situation as dire as you’re making out? On the other hand, it’s pretty smart. Of course, there are serious privacy issues involved in giving money to a random stranger through an app like Venmo, it’s not private, so I probably wouldn’t do that either, but it’s an interesting idea, if it could be made more anonymous and secure. Apparently, at least in China,

It has been a little over a week since the redacted Mueller Report was released, and so many words have been spilled that there could be a drought by summer if the umbrage reservoirs are not refilled. Can we just retire the word “closure”?

It has been a little over a week since the redacted Mueller Report was released, and so many words have been spilled that there could be a drought by summer if the umbrage reservoirs are not refilled. Can we just retire the word “closure”?

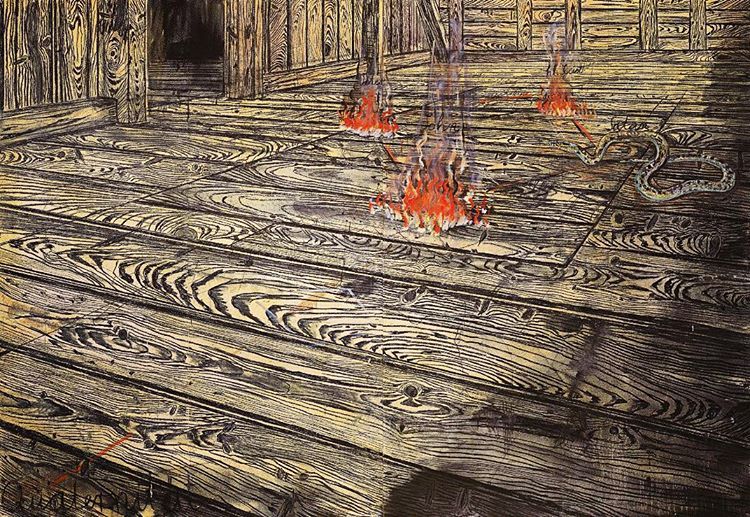

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

Last time

Last time It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1].

It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1]. A brief scan across global politics generates concerns as to what is actually going on in the politics of many states. Authoritarian regimes have always been with us, and will probably be with us for some time to come. Of greater concern is the emergence of political leaders in liberal democracies who espouse a politics which resonates with the past: a politics of nationalism, and nativism, and the inward-looking thinking that is associated with those ideologies. This trend, in what I would call a ‘regressive politics’, is in opposition to the process of globalisation.

A brief scan across global politics generates concerns as to what is actually going on in the politics of many states. Authoritarian regimes have always been with us, and will probably be with us for some time to come. Of greater concern is the emergence of political leaders in liberal democracies who espouse a politics which resonates with the past: a politics of nationalism, and nativism, and the inward-looking thinking that is associated with those ideologies. This trend, in what I would call a ‘regressive politics’, is in opposition to the process of globalisation.