by Robert Fay

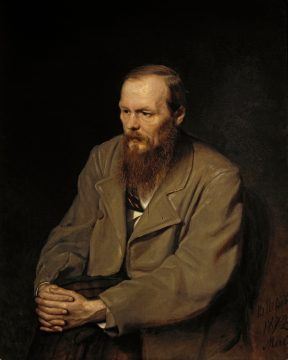

The great critic George Steiner in his book Tolstoy or Dostoevsky? (1959) believed the achievements of Russian literature in the 19th century stand as one of “three principal moments of triumph in the history of western literature, the other two being the Athenian dramatists and Plato and the age of Shakespeare.” Not particularly bad for a largely peasant-filled country whose entire literary tradition to that point was arguably in the form of just one man’s oeuvre: Alexander Pushkin. “His works,” Steiner notes, “constituted in themselves a body of tradition.”

But if the Russians didn’t have the bedrock cultural traditions of the their European neighbors—ancient Greek and Roman Civilizations, along with the unifying force of the Roman Catholic Church—they certainly had God, and God in Russia meant one thing: the Russian Orthodox Church.

In the 19th Century, the European intellectual and artistic environment was animated by the Enlightenment, whose denouement was surely the decapitation of France’s ancien régime in 1789, and with it, much of the legitimacy of “state, church and people” being understood as a unified, divinely-sanctioned manner of organizing human society and culture.

But by not being definitively western, either in geography or in the totality of its cultural inheritance, Russia had much in common with that one-time bastard of Europe, the United States of America, which in the 19th Century was still very much grappling with God as is evidenced by the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville, among others. Read more »

logician of modern times, at Einstein’s urging, brought his two magnificent proofs to Princeton. There he would remain for almost forty years, never mentoring a graduate student, rarely lecturing, adding only one substantial but incomplete proof to the cannon of math.

logician of modern times, at Einstein’s urging, brought his two magnificent proofs to Princeton. There he would remain for almost forty years, never mentoring a graduate student, rarely lecturing, adding only one substantial but incomplete proof to the cannon of math.

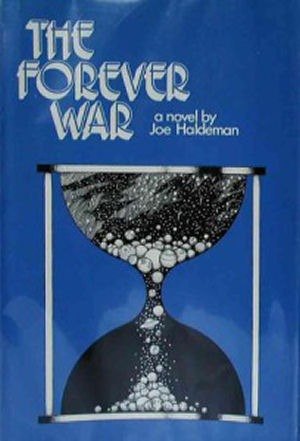

In 1974, noted science fiction author Joe Haldeman published a novel called The Forever War, which won several awards and spawned sequels, a comic version, and even a board game. The Forever War tells the story of William Mandella, a young physics student drafted into a war that humans are waging against an alien race called the Taurans. The Taurans are thousands of light years away, and traveling there and back at light speed leads Mandella and other soldiers to experience time differently. During two years of battle, decades pass by on Earth. Consequently, the world Mandella returns to each time is increasingly different and foreign to him. He eventually finds his home planet’s culture unrecognizable; even English has changed to the point that he can no longer understand it.

In 1974, noted science fiction author Joe Haldeman published a novel called The Forever War, which won several awards and spawned sequels, a comic version, and even a board game. The Forever War tells the story of William Mandella, a young physics student drafted into a war that humans are waging against an alien race called the Taurans. The Taurans are thousands of light years away, and traveling there and back at light speed leads Mandella and other soldiers to experience time differently. During two years of battle, decades pass by on Earth. Consequently, the world Mandella returns to each time is increasingly different and foreign to him. He eventually finds his home planet’s culture unrecognizable; even English has changed to the point that he can no longer understand it.

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.  Having before you an iced mango

Having before you an iced mango