by Robert Fay

The great critic George Steiner in his book Tolstoy or Dostoevsky? (1959) believed the achievements of Russian literature in the 19th century stand as one of “three principal moments of triumph in the history of western literature, the other two being the Athenian dramatists and Plato and the age of Shakespeare.” Not particularly bad for a largely peasant-filled country whose entire literary tradition to that point was arguably in the form of just one man’s oeuvre: Alexander Pushkin. “His works,” Steiner notes, “constituted in themselves a body of tradition.”

But if the Russians didn’t have the bedrock cultural traditions of the their European neighbors—ancient Greek and Roman Civilizations, along with the unifying force of the Roman Catholic Church—they certainly had God, and God in Russia meant one thing: the Russian Orthodox Church.

In the 19th Century, the European intellectual and artistic environment was animated by the Enlightenment, whose denouement was surely the decapitation of France’s ancien régime in 1789, and with it, much of the legitimacy of “state, church and people” being understood as a unified, divinely-sanctioned manner of organizing human society and culture.

But by not being definitively western, either in geography or in the totality of its cultural inheritance, Russia had much in common with that one-time bastard of Europe, the United States of America, which in the 19th Century was still very much grappling with God as is evidenced by the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville, among others.

*

Today there is great political and social tumult in many western liberal democracies and the stakes are high. The European Parliamentary elections are taking place and it’s expected the results will reflect that tension, particularly in the form of support for far-right populist parties. But today’s societal friction pales in comparison to the fissures and clashing ideals present in mid-to-late 19th Century Russia, Steiner notes, ticking off the list:

“..an affrighted despotism; a Church preyed upon by apocalyptic despotism; an immensely gifted but uprooted intelligentsia seeking salvation either abroad or in the tenebrous mass of the peasantry…a Europe they both loved and despised; the raging of debates of Slavophiles and Westernizers, Populists and utilitarians; reactionaries and nihilists, atheists and believers…”

This cultural turbulence is captured brilliantly by Dostoevsky in Demons (1871), which features a nearly overwhelming cast of characters and subplots worthy of Dickens—plus with a bit of dramatic humor and folly reminiscent of Shakespeare Midsummer’s Night Dream—all in the service of exploring the stew of ideas, including whether Russianness is intrinsically tied to the Church.

There is a particularly famous scene where Ivan Shatov, the son of a former serf, who is once again a believer after years of exploring radical ideologies, engages in a high-stakes clash-of-ideas with the novel’s central character Nikolai Stavrogin, the charismatic atheist looked on as the inevitable revolutionary leader. He is part Steve Bannon, Jerry Rubin and Rasputin, who once believed in Russia and Christ.

“Do you remember your expression,” Shatov says. “‘An atheist cannot be Russian, an atheist immediately ceases to be Russian’—remember that?”

Shatov continues. “I’ll remind you of more. ‘He who is not Orthodox cannot be Russian.’”

Today this long-buried belief has reemerged in the propaganda of the Putin regime, which has cozied up to the Russian Orthodox Church, in an attempt to define a new Russian patriotism to replace the vacuum left by communism. But it’s not working. In a 2015 study, the proportion of Russians believing religion does more good than harm to society, which was as high as 61% in 1990, is an anemic 36% these days.

And with the exception of the Law and Justice Party in Poland, evangelical Christians in the U.S. and Ultra-Orthodox Jews is Israel, few segments of western society are now explicitly trying to find harmonies between civil law and sacred scripture (the real energy on the political right today is with populist parties like Alternative for Germany, Trumpism in the U.S., and National Rally in France, parties/movements that don’t explicitly build their platforms around religious values).

*

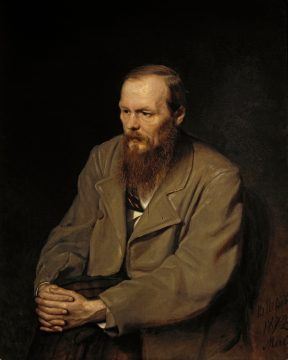

Joseph Frank in his definitive English biography of Dostoevsky, Dostoevsky: A Writer and his Time (2010)—an abridgement of his massive five-volume series—writes that Dostoevsky couldn’t conceive of Russia without the Orthodox church. Frank writes Dostoevsky believed the tragedy of Stavrogin was in the form a moral-religious one. “It is the search for an absolute faith that has been surrendered to the blandishments of the European Enlightenment and cannot yet be recaptured despite the torturing need for a ‘new truth.’”

“New truths,” are badly needed today, but instead, we only get old lies, recycled and represented as new options. The far-right populism of Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen may feel fresh to some, but it’s old, very old street pol tactics; and at its most benign, it’s rather boring stuff, intellectually vacant and built on rants and tropes. But if it gets supercharged, if it gets a boost, there is always the danger it can hook up with far more serious forces, whether ideological, religious or military—and then there is suddenly a real force behind the speeches. In other words, Italy’s deputy prime minister and Lega Nord party head, Matteo Salvini, might be a simple loudmouth or he might be much more. Let’s not find out.

In Demons faux intellectual Stepan Trofimovich goes on the kind of self-justifying political rant that has an echo of both the ISIS murderer, the Oregon white nationalist and the Chinese communist cadre of the 1960s: “As soon as there’s a tiny bit of family or love, there’s a desire for property. We’ll extinguish desire: we’ll get drinking, gossip, denunciation going; we’ll get unheard-of depravity going; we’ll stifle every genius in infancy. Everything reduced to a common denominator, complete equality.”

This is the creed of the fanatic. And If people have to die to make an idea a social reality, so be it.

Dostoevsky understood in 1871 what was coming. He knew the old order was doomed, and the Russian Empire would be toppled by radicals who used violence as a tool. One might say he predicted the Bolshevik Revolution of 1916 in Demons, where he writes, “Shatov insists to start a rebellion in Russia one must inevitably begin with atheism.”

Today the prediction might be, that to upend the liberal democracies, you must start by putting forth bullies, nationalists and racists as leaders, and start the name calling and depravity as soon as possible, because that will surely stifle debate, thoughtfulness and basic civic charity—which are always impediments to the agitator.

Stepan Trofimovich, of course, got the authoritarian revolution he wanted. It came in the 20th Century, in many forms and in many places, and it lives once more in the hearts of men and women who want power and who believe ideological or doctrinal purity will finally bring “order” to our chaotic, messy world.

*

There is a lovely old book on Dostoevsky that I fear is largely forgotten and likely out-of-print in English. It’s titled Dostoevsky (1923) and it’s a meditation on the Russian master by the French novelist Andre Gide, who is an astute observer of both European and Russian literature. Near the end of the book, he asks a simple question. A question that is just as applicable today considering the lies, brutalities and corruption centered, not on Lenin and the Bolsheviks as it was in Gide’s time, but on the Putin regime in St. Petersburg. “What would Dostoevsky think of Russia today and of her people? It is a painful speculation…Did he apprehend? Was he able to foresee her ghastly torments?”

Robert Fay’s essays, reviews and stories have appeared in The Atlantic, The Millions, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly Review, among others. He is co-creator of the Feeling Bookish Podcast. Follow him on Twitter @RobertFay1.