by Ashutosh Jogalekar

The Doomsday Scenario, also known as the Copernican Principle, refers to a framework for thinking about the death of humanity. One can read all about it in a recent book by science writer William Poundstone. The principle was popularized mainly by the philosopher John Leslie and the physicist J. Richard Gott in the 1990s; since then variants of it have have been cropping up with increasing frequency, a frequency which seems to be roughly proportional to how much people worry about the world and its future.

The Doomsday Scenario, also known as the Copernican Principle, refers to a framework for thinking about the death of humanity. One can read all about it in a recent book by science writer William Poundstone. The principle was popularized mainly by the philosopher John Leslie and the physicist J. Richard Gott in the 1990s; since then variants of it have have been cropping up with increasing frequency, a frequency which seems to be roughly proportional to how much people worry about the world and its future.

The Copernican Principle simply states that the probability of us existing at a unique time in history is small because we are nothing special. We therefore must exist roughly close to half the period of our existence. Using Bayesian statistics and the known growth of population, Gott and others then calculated lower bounds for humanity’s future existence. Referring to the lower bound, their conclusion is that there is a 95% chance that humanity will go extinct in 9120 years.

The Doomsday Argument has sparked a lively debate on the fate of humanity and on different mechanisms by which the end will finally come. As far as I can tell, the argument is little more than inspired numerology and has little to do with any rigorous mathematics. But the psychological aspects of the argument are far more interesting than the mathematical ones; the arguments are interesting because they tell us that many people are thinking about the end of mankind, and that they are doing this because they are fundamentally pessimistic. This should be clear by how many people are now talking about how some combination of nuclear war, climate change and AI will doom us in the near future. I reject such grim prognostications because they are mostly compelled by psychological impressions rather than by any semblance of certainty. Read more »

![Henri Matisse created many paintings titled 'The Conversation'. This, from 2012, is of the artist with his wife, Amélie. [Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia].](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Matisse_Conversation-360x292.jpg)

Books about how to write are so frequently described as life-changing and essential (usually by publishers, but sometimes by reviewers) that I was initially unmoved by enthusiastic reviews of Clear and Simple as the Truth: Writing Classic Prose, by Francis-Noël Thomas and Mark Turner. However, the praise seemed to focus on the fact that the book had changed the reviewers’ attitudes toward what writing is and how it works, and that interested me. I decided to get a copy, and I’m glad I did. The book describes and illustrates a particular style of writing but also, and perhaps more importantly, it really did give me a different framework for thinking about what style is and, yes, what writing is.

Books about how to write are so frequently described as life-changing and essential (usually by publishers, but sometimes by reviewers) that I was initially unmoved by enthusiastic reviews of Clear and Simple as the Truth: Writing Classic Prose, by Francis-Noël Thomas and Mark Turner. However, the praise seemed to focus on the fact that the book had changed the reviewers’ attitudes toward what writing is and how it works, and that interested me. I decided to get a copy, and I’m glad I did. The book describes and illustrates a particular style of writing but also, and perhaps more importantly, it really did give me a different framework for thinking about what style is and, yes, what writing is.  Did completing your taxes seem a Herculean task? Did cleaning your adolescent bedroom compare to mucking the Augean stables? Are you more jovial or saturnine by nature? Do you or anyone you know suffer from narcissism? Did you see the movie Titanic? Have you ever been hypnotized? Do you want to go on an odyssey? These questions are all so tantalizing, no?

Did completing your taxes seem a Herculean task? Did cleaning your adolescent bedroom compare to mucking the Augean stables? Are you more jovial or saturnine by nature? Do you or anyone you know suffer from narcissism? Did you see the movie Titanic? Have you ever been hypnotized? Do you want to go on an odyssey? These questions are all so tantalizing, no? The relation between what is natural and what is morally good is a topic that has concerned philosophers from ancient times to the present. Those who view the part of a human being that belongs to the material world as sordid, unclean, and irrational have understood morality to require the suppression or the taming of nature; the angel in us must control the beast. This outlook is endorsed by Plato and is commonly found in Christian theology. Hobbes’ social contract theory, which presents moral life and political order as the way we escape the miseries of the state of nature, also takes morality and nature to be in certain respects opposed. Many others, though, have looked to nature for some sort of moral guidance. The Stoics viewed the implacable order observed in the heavens as a model for a serene human life. Defenders of rigid social hierarchies pointed to the successful arrangements in a bee hive. Critics of homosexuality argue that it is “unnatural,” while advocates of gay rights deny this. Appeals to what one finds in nature have bolstered social Darwinism, the subordination of women, arguments for and against slavery, egalitarianism, and the idea of universal human rights.

The relation between what is natural and what is morally good is a topic that has concerned philosophers from ancient times to the present. Those who view the part of a human being that belongs to the material world as sordid, unclean, and irrational have understood morality to require the suppression or the taming of nature; the angel in us must control the beast. This outlook is endorsed by Plato and is commonly found in Christian theology. Hobbes’ social contract theory, which presents moral life and political order as the way we escape the miseries of the state of nature, also takes morality and nature to be in certain respects opposed. Many others, though, have looked to nature for some sort of moral guidance. The Stoics viewed the implacable order observed in the heavens as a model for a serene human life. Defenders of rigid social hierarchies pointed to the successful arrangements in a bee hive. Critics of homosexuality argue that it is “unnatural,” while advocates of gay rights deny this. Appeals to what one finds in nature have bolstered social Darwinism, the subordination of women, arguments for and against slavery, egalitarianism, and the idea of universal human rights.

The authority of scientific experts is in decline. This is unfortunate since experts – by definition – are those with the best understanding of how the world works, what is likely to happen next, and how we can change that for the best. Human civilisation depends upon an intellectual division of labour for our continued prosperity, and also to head off existential problems like epidemics and climate change. The fewer people believe scientists’ pronouncements, the more danger we are all in.

The authority of scientific experts is in decline. This is unfortunate since experts – by definition – are those with the best understanding of how the world works, what is likely to happen next, and how we can change that for the best. Human civilisation depends upon an intellectual division of labour for our continued prosperity, and also to head off existential problems like epidemics and climate change. The fewer people believe scientists’ pronouncements, the more danger we are all in.

Growing up, a lighter branded you as suspect to any Baptist worth his King James Version. Because really, other than smoking and setting houses on fire to incinerate the family within just for kicks, what did you need a lighter for anyway? If you wanted to light something righteous like a candle or the water heater, you reached for the box of safety matches next to the paprika in the spice cabinet. They had SAFETY written on the box in case you felt tempted to go astray. Lighters should have had Iniquity Equipment inscribed on them as far as we were concerned.

Growing up, a lighter branded you as suspect to any Baptist worth his King James Version. Because really, other than smoking and setting houses on fire to incinerate the family within just for kicks, what did you need a lighter for anyway? If you wanted to light something righteous like a candle or the water heater, you reached for the box of safety matches next to the paprika in the spice cabinet. They had SAFETY written on the box in case you felt tempted to go astray. Lighters should have had Iniquity Equipment inscribed on them as far as we were concerned.

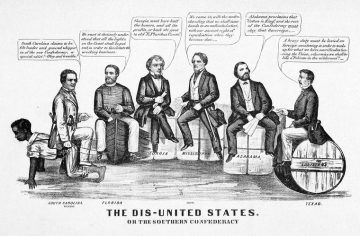

By the time Sherman’s armies had scorched and bow-tied their way to the sea, by the time Halleck had followed Grant’s orders to “eat out Virginia clean and clear as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender with them,” and by the time Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was finished squeezing every drop of life out of the Confederacy, there had to be those who wondered what possible logic would lead intelligent men like Jefferson Davis to make such a catastrophic choice.

By the time Sherman’s armies had scorched and bow-tied their way to the sea, by the time Halleck had followed Grant’s orders to “eat out Virginia clean and clear as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender with them,” and by the time Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was finished squeezing every drop of life out of the Confederacy, there had to be those who wondered what possible logic would lead intelligent men like Jefferson Davis to make such a catastrophic choice.

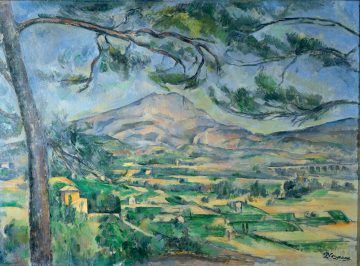

Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.

Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.