by Thomas Manuel

Born in France in the mid-14th century, Christine de Pizan wrote possibly the first work of women’s history that was by a woman for women. She remains one of the era’s most fascinating writers but considerably less well-known than other writes of her time like travelling scholar and professional complainer, Ibn Battuta, or Christian fan fiction writer extraordinaire, Dante Alighieri. Her father was a kind of royal astrologer to the King of France and growing up at the court, she probably received an excellent education. But, in her own words, she only really experienced the “sweet taste of learning” when her husband died. Widowed in her twenties and with children to raise, Christine de Pizan began a remarkable literary career which gave us among other works, Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (‘The Book of the City of Ladies’).

City of Ladies is a reaction against the rampant misogyny that so deeply permeated Christine’s time. In the book, she laments that every book by a male writer that she opens has some sexist generalization about women. Amidst all of this, the specific instigating factor was an extremely popular romance that had been published called La Roman de Rose (‘The Story of the Rose’). This romance was an epic poem of two parts. The first part predates the second by about half a century and is all about chivalrous love. The second (and much larger) part, written by a different author, takes a much more cynical view of love, essentially labeling all women as cruel seducers. (Clearly, the universe is crying out for a 600 page History of the Incels.) Christine publicly lambasted the book and wrote City of Ladies as a counterweight, becoming in the words of Simone de Beauvoir, the first woman to “take up her pen in defence of her sex.”

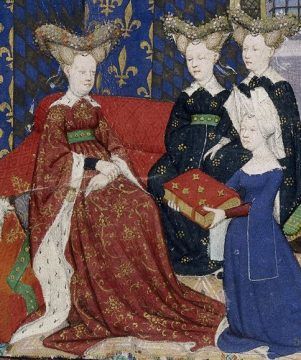

In the book, Christine is visited by three figures – Lady Reason, Lady Rectitude and Lady Justice who ask her to build a city just for women. Led by the three Ladies, Christine builds a city, inviting famous women to live there. From Eve (whose story is the ground zero of misogyny in the Christian tradition) to the ass-kicking Amazons, from contemporaries like Maria, the Duchess of Auvergne, to historical icons like Sappho or mythological beings like Medusa, Christine tells their stories, elaborating on their various virtues. And so the city, filled with poets and queens, saints and warriors, becomes a living monument to the place of women in history.

This wide-ranging piece of scholarship is an even greater achievement because Christine had so little in the way of precedent. (And she says as much in the book.) There had been other works that sought to catalogue women through history but they were written male authors and it showed. Boccaccio’s Famous Women mostly contained infamous women and Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women had the author literally claiming that God forced him to write the book as punishment. These books do nothing for the cause of women. Christine, on the other hand, was building an argument as surely as she was building a city.

Her arguments are overtly religious – after all, her title is a reference to Thomas Aquinas’ City of God. Using the language of theology, Christine argues that misogyny is a form of heresy, an attack on man’s noble and vital equal in front of God. Much of Christine’s reasoning and opinions are not really “feminist”, coming from a time before the ideas of the movement were ever formed. As Rosalind Brown Grant says in Christine De Pizan And The Moral Defence Of Women, “Those who have offered an assessment of her defence of women have tended to adopt one of two contrasting positions: whilst some have praised Christine for challenging the dominant misogynist ideology of her age, even lauding her ability to anticipate key tenets of post-structuralist feminist theory, others have castigated her for failing to advocate reform of the social order or to demand equal rights for women. Yet these wildly divergent assessments of Christine’s work can be faulted on common grounds: both ignore her original cultural context and judge her by criteria which are fundamentally anachronistic. Positive or negative, such judgments tell us more about what modern feminists might wish Christine to have achieved, as opposed to what she herself sought to achieve in her campaign to champion the cause of women.”

The City of Ladies is Christine de Pizan being a public intellectual and, quoting John Dewey said, publics don’t exist, they are created. Through this book, Christine was speaking to ordinary women (how ordinary is debatable) and creating a history for them (and herself). The lessons from the women in the book are meant to be accessible and applicable in her readers’ lives. Christine’s city of role models and inspirations was a polemic constructed to combat the widespread misogynist view of womanhood spread by so many male writers and intellectuals of the time. Of course, 600 years later, it is hard to say times have changed. As historian Sharon Jensen wrote in Reading Women’s Worlds from Christine de Pizan to Doris Lessing, “At the turn of the fifteenth century, Christine de Pizan already has a room of her own, and she has found that a room is not enough. She offers women an entire city—it’s an audacious act. Her fifteenth-century daring still shocks twenty-first century readers.”