by Joseph Shieber

There’s an interesting reaction that I sometimes get from my colleagues in the natural sciences when I describe what I do. When I talk about epistemology – the study of knowledge – I often hear a version of the following response.

“Well, in the sciences we don’t really deal with knowledge at all. At best, we have a high degree of confidence in a claim, but we’d never say that we know it.”

In the faculty dining room, there’s seldom time seriously to discuss philosophy with faculty from other disciplines. Also, if I tried it, I might find myself sitting alone in the very near future. So I thought I’d take this opportunity to respond to my (imaginary) colleague.

To do so, I want to start by considering an argument of Saul Kripke’s. Kripke achieved fame early as a philosophical prodigy. He enjoyed widespread acclaim within the philosophical community first for his work in modal logic and later for his work in metaphysics, philosophy of language, and the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Kripke’s reputation also stemmed from his virtuoso lectures. He was able to lecture without notes on complex topics, the complete paragraphs tumbling out of his mouth, seemingly effortlessly. He was equally known as someone reluctant to put his ideas to paper, so for years many of the arguments attributed to him circulated in samizdat versions taken from notes from his lectures.

In the years in which many of Saul Kripke’s arguments circulated by word of mouth or in third-party notes of lectures, one of the most famous is what we can call the “Paradox of Knowledge’ argument. Read more »

I was perhaps ten years old when I had unending cups of Eatmore’s fresh handmade mango ice cream while sitting on the lawns of Services Club Sialkot. It was one of the brightest days of my life, with my parents all to myself, undistracted by the demands of their daily doings, and the crystal cups of ice cream brought to us. We sat on reclining garden chairs on the perfectly manicured lawn, bordered by fragrant

I was perhaps ten years old when I had unending cups of Eatmore’s fresh handmade mango ice cream while sitting on the lawns of Services Club Sialkot. It was one of the brightest days of my life, with my parents all to myself, undistracted by the demands of their daily doings, and the crystal cups of ice cream brought to us. We sat on reclining garden chairs on the perfectly manicured lawn, bordered by fragrant

If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry?

If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry?

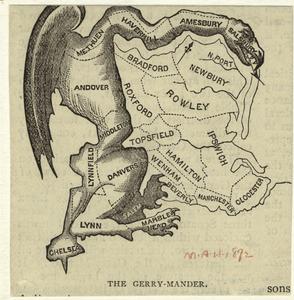

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.

Several co-workers, all of whom have Ph.D.s. An old friend who’s a physicist. Scads of family members of both blue and white collar variety. Numerous neighbors. And of course the well dressed, kindly old women who occasionally show up at my door uninvited, pamphlets in hand.

Several co-workers, all of whom have Ph.D.s. An old friend who’s a physicist. Scads of family members of both blue and white collar variety. Numerous neighbors. And of course the well dressed, kindly old women who occasionally show up at my door uninvited, pamphlets in hand.