by Liam Heneghan

The Art Institute of Chicago is unremarkable in this one respect: like every world class art museum its galleries teem with works representing indefatigable artistic industry besieged by the entropic desolation that all the works of humankind are heir to.

Our lot is to amass and assemble; the universe responds, dispassionately, with decay and dispersion. Millennia of creative effort crumble away. Walk through any decent sized art museum and behold the craquelure of old oils, the loss of patina in the watercolors, the splintering of carved wood, dents in metalwork, and the extremities snapped off old stonework. Can there be a pleasure in art that is completely unhinged from the intimations of loss ? The sense of loss that decay evokes may intensify pleasure if you incline to morbidity.

*

One late afternoon in the middle of March, I dropped by the Art Institute of Chicago on my way home from work. A late season snow was falling. As I scurried across Michigan Avenue from my train toward the museum, I was covered in a thin and fluffy white rind. A clump of slush fell from my hat and onto my notebook as I stood in the entrance hall.

My plan was to walk a fairly straight line from the Michigan Avenue entrance though the galleries and egress the building through the modern wing. That route favors. If one does not deviate into, say, the prints and drawings gallery, or into the Japanese alcoves, works of considerable antiquity are on display: Chinese, Korean, Himalayan, Byzantine, Roman, Greek.

Methodologically, my plan had been to catalog the injuries to every object I encountered along my way.

Such is the density of works along my short route, and such is the immensity of assault on the objects along my antiquarian trail (for example, a single gilt copper alloyed bust can be tarnished in patterns variegated, and dinged up besides), that the task overwhelmed me almost immediately. I was, besides, cold and wet and gently steaming.

The security personnel, though not intrusive, were strenuously watchful of me about my task. A student of attrition behaves erratically, I suppose.

In the end, I favored a qualitative “gestalt” approach to evaluating decay rather than the strictly quantitative cataloging that I had intended.

*

Every cultural object that remains (relatively) intact is intact in an uncomplicated way; every damaged object seems damaged along unique lines. Yet the debilitation of art is not completely capricious. One notices quickly the robustness of basaltic sculptures, that schists hold up, and that aging andesite becomes pockmarked. One notices the points of vulnerability of the sculpted human body—hands, arms, noses, genitals, especially genitals, are susceptible.

The gods and their faithful acolytes are not spared time’s corrosive wand.

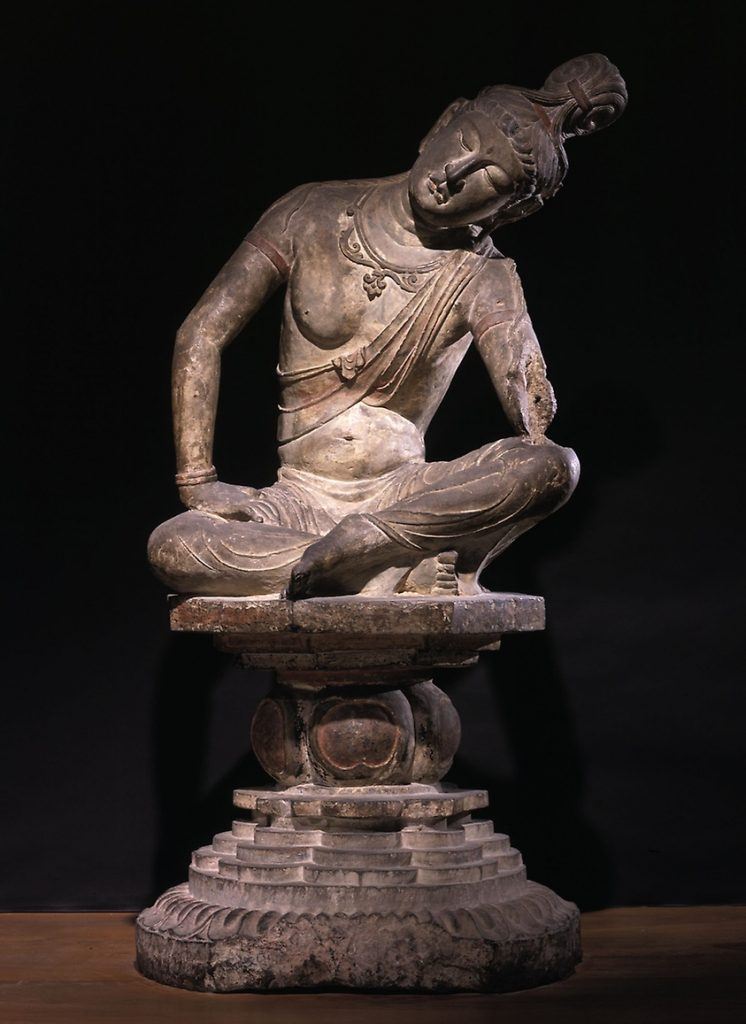

The formidable limestone Buddha that you encounter passing into the Chauncey McCormick Gallery and that dates to the early 8th Century is marred in divers ways. Both arms are damaged, one broken cleanly, the other has frayed as if the limb was simply withering away. One of his ears is as cauliflowered as that of an end-career boxer. Two representations of Buddhist monks from the 5th Century appear serene despite being handless. A remarkable seated Chinese Bodhisattva from the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618–907) has one hand at rest on his thigh; his torso inclines to the left as though he aimed to balance himself by resting his forearm on his other thigh. That forearm is gone; for the time being, at least, he appears to be holding himself up in a strainful and improbably manner. No doubt at some distant point in the future he will simply topple asunder.

I continued marching along—now in the Alsdorf Gallery—which bristles with tremendous broken things. There you will see that the Indian gods have fared no better. An Eight-Armed Dancing Ganesha from the 17th or 18th century, carved from wood, is missing one tusk (perhaps by design); two of that god’s hands are long gone. A 12th century sandstone goddess from the Cambodian Angkor period has lost her head, both arms, both legs from the knees down. A representation of the Goddess Hariti Seated Holding a Child, dating from the Indian Pala period, (10th/11th century) and constituted from black stone is breastless. Her face: featureless.

My task becomes almost unbearable as I continue past wrecked Javanese statues—many of them constituted from andesite and thus often feature-poor, and pocked marked—and on into the Mary and Michael Jaharis Gallery of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine art. I survey the damage: starting with a truly remarkable portrait of Julius Caesar, and passed in sequence, a Statue of Sophocles (2nd Century), the Head of an African Man (1st or 2nd Century), a Portrait Head of Man (27 BC/AD 14), a Statue of a Young Boy (1st Century), a Portrait of a Woman (AD100/25), the Head of a Man (Perhaps a Barbarian) (AD 100/125), and a Portrait Head of Emperor Hadrian (AD 130/238). All are comprised of marbles, and with the pleasing exception of Sophocles, all had lost their noses.

By this stage of my macabre journey, I was making for the door, barely taking in the smashed ceramics, the shards cataloged and sportily displayed, and averting my eyes from some funerary relics so worn as to be virtually faceless.

I sped though the enormous hall of the new modern wing, and was spat out into the gently swirling snow. Back now in the maw of Chicago—the city of Big Shoulders, City in a Garden, The Windy City, The Second City, Murder City—a city that for a century and a half has tried to marshal the forces of repair to halt its attrition.

I hopped on the Red Line—crowded and winter-aromatic—heading north.

Liam Heneghan’s briskly selling new book is Beasts at Bedtime: Revealing the Environmental Wisdom in Children’s Literature (University of Chicago Press, 2018) available here or here. He is currently writing on art restoration. He tweets @DublinSoil