by Chris Horner

The question of how to program AI to behave morally has exercised a lot of people, for a long time. Most famous, perhaps, are the three rules for robots that Isaac Asimov introduced in his SF stories: (1) A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm; (2) A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law; (3) A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law. These have been discussed, amended, extended and criticised at great length ever since Asimov published them in 1942, and with the current interest in ‘intelligent AI’ it seems they will be subject for debate for some time to come. But I think the difficulties of coming up with effective rules of this kind are more interesting for what they tell us about the difficulties of any rule or duty based morality for humans than they are for the question of ‘AI morality’.

Duty based – the jargon term is ‘deontological’ – morality seem to run into problems as soon as we imagine them being applied. Duties can easily seem to clash or lead to unwelcome outcomes – one might think that lying would be justified if it meant protecting an innocent person from a violent person set on harming them, for instance. So which duties should take precedence in the infinite number of future situations in which they might be applied? Answering a question like that involves more than coming up with a sequence of rules, as there seems to be something one needs to add to any would-be moral agent for them to really exercise an adequate moral judgment. Considering the problems around this is more than a philosophical parlour game as it should lead us into more realistic ways of thinking about what it takes to act well in the real world. What we are looking for, I think, is an approach that takes into account the need for genuinely autonomous moral thinking, but also connects the moral agent to the the complicated social world in which we live. Read more »

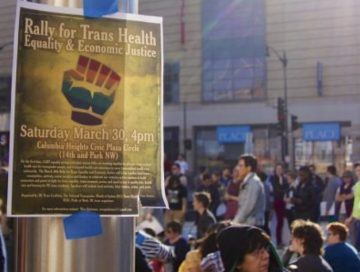

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now?

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now? Einstein had called nationalism ‘an infantile disease, the measles of mankind’. Many contemporary cosmopolitan liberals are similarly skeptical, contemptuous or dismissive, as its current epidemic rages all around the world particularly in the form of right-wing extremist or populist movements. While I understand the liberal attitude, I think it’ll be irresponsible of us to let the illiberals meanwhile hijack the idea of nationalism for their nefarious purpose. Nationalism is too passionate and historically explosive an issue to be left to their tender mercies. It is important to fight the virulent forms of the disease with an appropriate antidote and try to vaccinate as many as possible particularly in the younger generations.

Einstein had called nationalism ‘an infantile disease, the measles of mankind’. Many contemporary cosmopolitan liberals are similarly skeptical, contemptuous or dismissive, as its current epidemic rages all around the world particularly in the form of right-wing extremist or populist movements. While I understand the liberal attitude, I think it’ll be irresponsible of us to let the illiberals meanwhile hijack the idea of nationalism for their nefarious purpose. Nationalism is too passionate and historically explosive an issue to be left to their tender mercies. It is important to fight the virulent forms of the disease with an appropriate antidote and try to vaccinate as many as possible particularly in the younger generations.

The roof of Notre-Dame de Paris, lost in the fire of April 15, 2019, was nicknamed The Forest because it used to be one. It contained the wood of around 1300 oaks, which would have covered more than 52 acres. They were felled from 1160 to 1170, when they were likely several hundred years old. It has been estimated that there is no similar stand of oak trees anywhere on the planet today.

The roof of Notre-Dame de Paris, lost in the fire of April 15, 2019, was nicknamed The Forest because it used to be one. It contained the wood of around 1300 oaks, which would have covered more than 52 acres. They were felled from 1160 to 1170, when they were likely several hundred years old. It has been estimated that there is no similar stand of oak trees anywhere on the planet today.

This essay is about technology, probably. I waffle on the theme only because I think blaming existential panic on cell phones is stale, but I’m pretty sure it’s accurate! Let me make my case. I’ve opened Mario Kart Mobile Tour on my phone three times since starting to write this and I’m not yet on my third paragraph. And I’ve already raced all the races and gotten enough stars to pass each cup. And I still keep opening the app. This week it’s Mario Kart, but before that it was Love Island The Game and before that it was Tamagotchi (and Solitaire and Candy Crush and and and). I don’t have a Twitter and I rarely open Instagram so presumably the games are just the most enticing apps I have, but it’s still gross how long I spend with my shoulders tightened, neck tensed, and thumbs exercising. I feel like a loser. And I justify all the time, pretending like I’m having such deep thoughts in the background as I throw red turtle shells. I try to map life onto the racing track; I look for metaphors as I complete a lap and am satisfied with exercising the poetic side of my brain for the day.

This essay is about technology, probably. I waffle on the theme only because I think blaming existential panic on cell phones is stale, but I’m pretty sure it’s accurate! Let me make my case. I’ve opened Mario Kart Mobile Tour on my phone three times since starting to write this and I’m not yet on my third paragraph. And I’ve already raced all the races and gotten enough stars to pass each cup. And I still keep opening the app. This week it’s Mario Kart, but before that it was Love Island The Game and before that it was Tamagotchi (and Solitaire and Candy Crush and and and). I don’t have a Twitter and I rarely open Instagram so presumably the games are just the most enticing apps I have, but it’s still gross how long I spend with my shoulders tightened, neck tensed, and thumbs exercising. I feel like a loser. And I justify all the time, pretending like I’m having such deep thoughts in the background as I throw red turtle shells. I try to map life onto the racing track; I look for metaphors as I complete a lap and am satisfied with exercising the poetic side of my brain for the day.

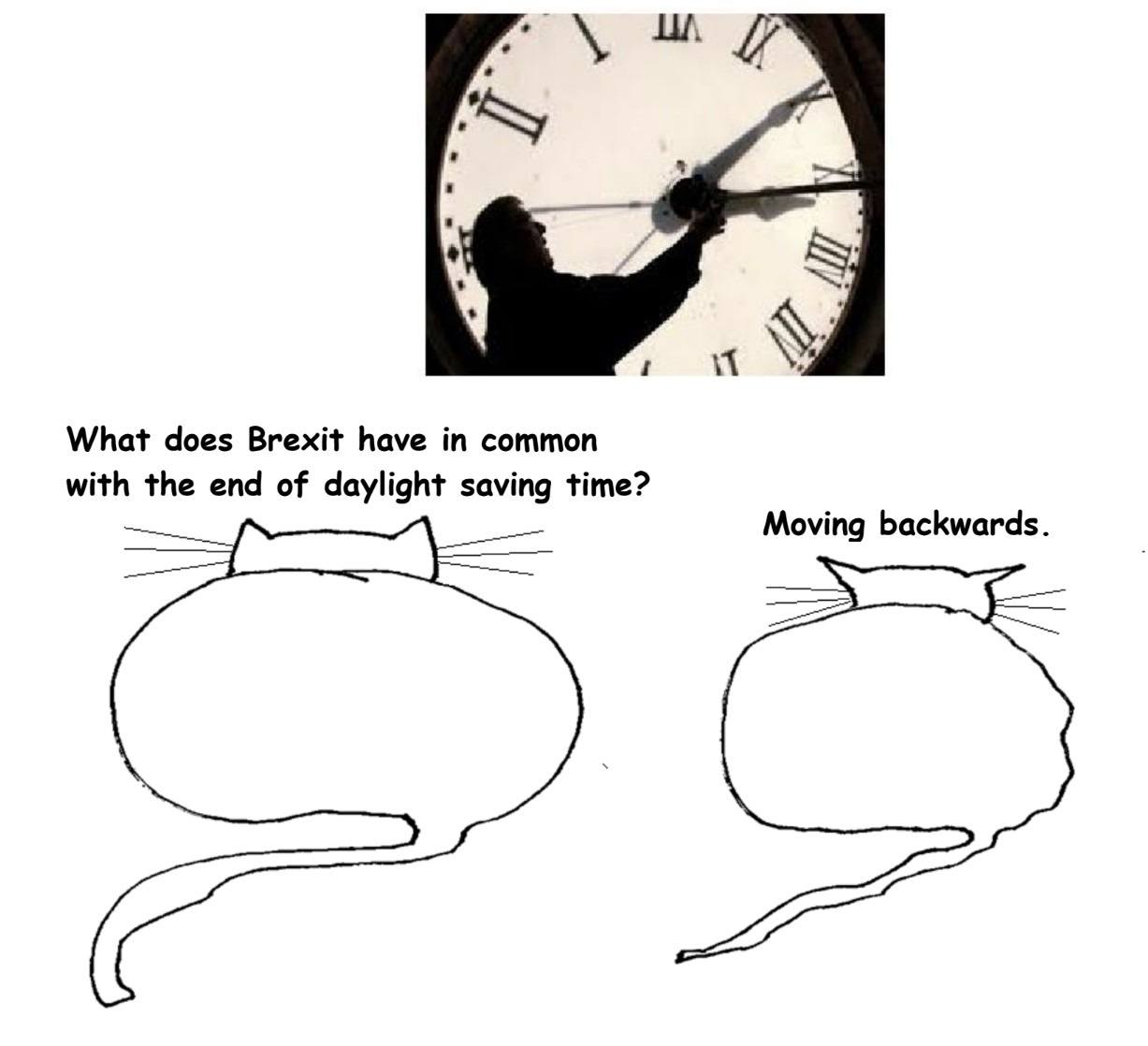

Fantasy politics starts from the expectation that wishes should come true, that the best outcome imaginable is not just possible but overwhelmingly likely. Brexit is classic fantasy politics, premised on the delightful optimism that if the UK were only freed of its shackles it would easily be able to negotiate the best deals imaginable.

Fantasy politics starts from the expectation that wishes should come true, that the best outcome imaginable is not just possible but overwhelmingly likely. Brexit is classic fantasy politics, premised on the delightful optimism that if the UK were only freed of its shackles it would easily be able to negotiate the best deals imaginable.