by Priya Malhotra

Virtue wasn’t always gentle.

In ancient Rome, virtus was a word of force and visibility. It came from the Latin word vir, meaning “man,” and encompassed ideals of military bravery, civic leadership, and public excellence. A virtuous man was someone who acted decisively in the public sphere—whether in war, politics, or the courts. Virtus was not about goodness in the moral sense. It was about fulfilling one’s public role with courage and competence. The term belonged to action, and it was earned through what one did, not what one avoided.

But like many powerful words, virtus changed as it traveled. As Latin gave way to the languages of medieval Europe, and Christianity replaced classical philosophy as the dominant moral framework, the term began to morph. Virtus became vertu, and then “virtue.” Its meaning narrowed, softened, and interiorized. Instead of valor, it came to suggest moral purity, humility, and patience. Instead of a call to public greatness, it became a standard of private behavior—especially for women.

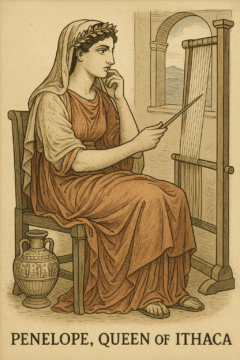

By the late Middle Ages, “virtue” in women had become nearly synonymous with chastity. It was a euphemism for sexual propriety, and a woman’s moral worth was often judged not by her integrity or courage, but by whether she had preserved her virginity, and later, her marital fidelity. Her virtue was not something she earned through action, but something she was expected to carry—like a fragile inheritance, one that could be irreparably lost. The woman who guarded her virtue was good; the one who “lost” it, no matter the context, was fallen.

The consequences of this shift weren’t merely symbolic. They shaped how women were viewed, valued, and remembered. A woman’s virtue could determine her marriage prospects, her reputation, and her legal status. It was both an irrevocable statement of her morality and a form of social capital. And over time, traits such as restraint, silence, and obedience became associated with female virtue.

This didn’t mean women completely lacked agency or complexity. They made difficult moral decisions constantly—often in conditions of constraint. But there was scant moral language to describe and give credit to those decisions or actions. Only when a woman’s strength came in the form of patience or sacrifice, was it sanctified. However, when it came in the form of autonomy or ambition, it was seen as far from praiseworthy.

You can see this dynamic clearly in the story of Penelope, queen of Ithaca in Homer’s Odyssey. Read more »

It is now close to 20 years since I completed my Ph.D. in English, and, truth be told, I’m still not exactly sure what I accomplished in doing so. There was, of course, the mundane concern about what I was thinking in spending so many of what ought to have been my most productive years preparing to work in a field not exactly busting at the seams with jobs (this was true back then, and the situation has, as we know, become even worse). But I’ve never been good with practical concerns; being addicted to uselessness, I like my problems to be more epistemic. I am still plagued with a question: Could I say that what I had written in my thesis was, in any particular sense, “true?” Had I not, in fact, made it all up, and if pressed to prove that I hadn’t, what evidence could I bring in my favour? Was what I saw actually “in” the text I was studying?

It is now close to 20 years since I completed my Ph.D. in English, and, truth be told, I’m still not exactly sure what I accomplished in doing so. There was, of course, the mundane concern about what I was thinking in spending so many of what ought to have been my most productive years preparing to work in a field not exactly busting at the seams with jobs (this was true back then, and the situation has, as we know, become even worse). But I’ve never been good with practical concerns; being addicted to uselessness, I like my problems to be more epistemic. I am still plagued with a question: Could I say that what I had written in my thesis was, in any particular sense, “true?” Had I not, in fact, made it all up, and if pressed to prove that I hadn’t, what evidence could I bring in my favour? Was what I saw actually “in” the text I was studying?

Sughra Raza. Colorscape, Celestun, Mexico. March 2025.

Sughra Raza. Colorscape, Celestun, Mexico. March 2025.

Lana Del Rey exists in a meticulously crafted world of her own. It’s a world apart. I purchased an invite to drop-by this summer, so that I might glimpse its finer details. Along with the crowd at the Anfield stadium in Liverpool, I was standing at its perimeter, gazing inwards, wondering. The atmosphere seemed rarified, there were even lily pads on the custom-built pond.

Lana Del Rey exists in a meticulously crafted world of her own. It’s a world apart. I purchased an invite to drop-by this summer, so that I might glimpse its finer details. Along with the crowd at the Anfield stadium in Liverpool, I was standing at its perimeter, gazing inwards, wondering. The atmosphere seemed rarified, there were even lily pads on the custom-built pond.

Today’s modest topic is the future of the West. Will it end in a bang, whimper or maybe just sort of muddle through in some zombie stagger? Whatever happens, a quarter of the way through the American Century, the standard of liberal democracy we hoisted as global inevitability twenty years ago hangs by the scruff of the neck and its enemies are eager to boot it straight into irrelevance.

Today’s modest topic is the future of the West. Will it end in a bang, whimper or maybe just sort of muddle through in some zombie stagger? Whatever happens, a quarter of the way through the American Century, the standard of liberal democracy we hoisted as global inevitability twenty years ago hangs by the scruff of the neck and its enemies are eager to boot it straight into irrelevance.