by Liam Heneghan

No one warned me that after my children finally left home when I secured the doors at night I would, in effect, be locking them out.

People deal with the mild trauma of being an “empty nester” in different ways, I suppose. Some handle it with quiet grace, some move cocktail hour to the early afternoon, some repurpose the bedrooms into a karaoke lounge, a discotheque and so on. I took the quieter route and reread all their childhood books—from nursery rhymes to the Hunger Games series and other novels for young adults.

I was first struck by the prevalence of animals themes in these books. For example, in Eric Kincaid’s superb collection of Nursery Rhymes (1990)—a favourite of our two boys—over forty percent of rhymes concern animals. However, a word search of a book I subsequently wrote on the topic of nature in children’s books called Beasts at Bedtime (2018) showed that I might just as well have called it “Trees at Bedtime.” In addition to the innumerable references to “beasts”, there are almost 200 references to trees in the book.

Trees are represented in these stories in all their remarkable forms: magical trees in fairy tales to trees like JK Rowling’s compellingly violent Whomping Willow at Hogwarts.

It is clear that many writers of children’s stories—especially the so-called classic writers—did not accidentally stumble onto such themes. Beatrix Potter, JRR Tolkien, Ursula LeGuin and many others, had a keen eye for nature, and often had an acute awareness of its devastation. The destruction of trees was a point of moderate obsession for Tolkien who famously wrote, “I take the part of trees as against all their enemies.”

What, I wonder, should we make of this veritable forest of arboreal allusions in children’s stories?

*

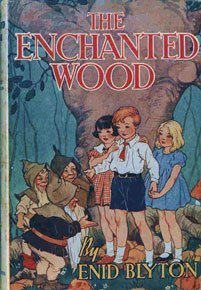

The very first tree I fell in love with was a fictional one. The Faraway Tree, in Enid Blyton’s The Enchanted Wood (1939) is a magical tree. It is discovered by three children—Jo, Bessie, and Fanny— who left grimy town-life and moved with their family to the country. The Faraway Tree represents the fabulous production of nature. Similar to the little nut tree of nursery rhyme fame, which produced a silver nutmeg, and a golden pear the Faraway grew acorns, chestnuts, and fruit of all sorts.

The Faraway Tree is a vision of delight and oddity—the tree was home to pixies!—it is besides, enticingly dangerous. As does Jack’s Magic Beanstalk, the Faraway tree connects our everyday world with strange lands above. The world above the Faraway tree is an appealing world for sure, but you never know what you will discover when you reach the top. At times, that world can be slightly monstrous (a recent reissue of the book has modulated the violence and it now errs on the side of polite caution).

*

Though the almost century-long debate on the merits of Enid Blyton’s literary production continues, without a doubt the Faraway Tree illustrates a familiar pattern in how storytellers describe a child’s relationship with trees. Trees are delightful and slightly ominous is equal measure.

In stories, individual trees can be appealing. For example, Shel Silverstein 1964 book about the morbidly generous Giving Tree remains a great favourite. Trees also fascinate in their collective presence in thickets, hedgerows, copses, woodlands, and forests. If your child is in need of soft comforts it is off to Winnie-the-Pooh’s Hundred-Acre Wood they should go. If it is healing that they need, then let them enter Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911) where the tendrils of the many rose-trees run in a “hazy tangle from tree to tree.”

For all their appeal both individually and en masse, humans, at times, find trees terrifying. What lurks aloft, behind, or occasionally even in them? In Tolkien’s Fellowship of the Ring (1954), for example, “Old Man Willow,” is a treelike creature inhabited by a sentient and malign soul.

So, if mild terror is your child’s cup of tea, they should indeed set off with Frodo Baggins through the Old Forest or perhaps get them a collection of Grimm Fairy Tales.

These fictional encounters with trees assure a child that though they too will head out the door on adventures, and will get into mischief, they can overcome obstacles and return, like Peter Rabbit, to the hearth.

*

Reading The Enchanted Wood as a child propelled me out the door to find my own Faraway Tree. Behind our house in Dublin was a field surrounded by some fine trees. My favourite was one we called the “B-B-L-O” (for reasons that none of the kids—now all grown—seem to recall). When I was twelve years old, the field was sold to a developer and all the trees came down. The children protested; no one listened. The destruction of trees—in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, for example—prepares children in fictional form for the potential losses of very real trees. Mildred Taylor Song of the Trees (1975) show how trees may be saved.

*

Those of us who have sent our fledglings out into the world call ourselves “empty nesters” as if we had raised them in trees. In fact, at the very top of our little house there is a very small loft that our two boys thought of as a tree house. Even if you don’t raise your children in a tree-crown, by reading to them you are at the very least raising them alongside trees. From fictional trees, they will learn of beauty, adventure, danger, and endurance before ever crossing the threshold.

Liam Heneghan is the author of Beasts at Bedtime: Revealing the Environmental Wisdom in Children’s Literature (University of Chicago Press, 2018) available here. A version of this essay was read on BBC Radio 4 (Open book).