by Samia Altaf

“This girl will never be able to find a husband,” declared Baiji, big mother, my maternal grandmother, soon after she took her first look at me.

“Hai hai,” she almost beat her chest, “look at her, just look.” She points at me holding herself back as if from a contaminant, appealing to the women — assorted aunts and cousins milling around, who hid their faces in their chadors and shook their heads — “her nose is too big, her eyes too small, she is bald.”

“And worst of all, hai hai,” — here Baiji’s voice drops ominously and a trembling hand goes to cover her mouth at the horror of it — “her color! It is not… not…not fair. It is… quite dark.”

She looks pityingly at my mother standing beside her in all her Kashmiri “fairness” and youthful glory — my mother of the fairest, luminous, skin that she took intact and unlined to her grave seven decades later — and puts a loving hand on her head. “My poor daughter… what a fate for you, hai hai. Well, at least these genes have not come from your side of the family.” (One of the aunts present at the occasion swears Baiji said germs and not genes.)

Baiji might as well have added, while on the roll, that the girl is also toothless and incontinent for I was all of a year old.

It is well known family lore that I, my mother’s third child, was a terrible disappointment to her. To start with, I was a girl, not a boy, clearly a lesser being in my grandmother’s male-biased house. To top that, I was “not fair”– a label of doom for girls in Pakistani society where the level of “fairness” determines her worth in the marriage market. All other things being equal, “not fair” is low. These two words buzzed around me like a swarm of bees circling my head wherever I went in the household of fair-skinned, light-eyed Kashmiri women and men. I had inherited my dear father’s dark — “wheatish,” when they were being charitable — genes, which can be tolerated in a male but, are absolutely unforgivable in a female. Saddled already with an active three-year old and an infant — both boys and both so “fair” — my mother was in no mood to deal with this bundle that did not come up to the family’s standard of beauty. If the boys, who did not need them much anyway, could manage to acquire those genes why couldn’t I?

Baby sister, proud inheritor of the fair genes, says mom started to cry when you were born. I don’t know about that — I like to think sis was just taking a catty- sibling swipe at me — but I do know that mom allowed a distant childless cousin on my father’s (un-fair) side to take me far away forcing my gentle and kind father to chase after on his Vespa scooter as she trundled off with me in her lap in a government transport bus enroute to Gujranwala bound for her village beyond. Fortunately for me the bus broke down on Grand Trunk road near Sambrial, just outside Sialkot, and my brave father rescued and brought the “unfair” me back, fat nose, dark complexion, and buzzing bees, all intact.

When she realized she could not get rid of me or ignore my presence as she had done during my childhood when I happily ran around climbing trees and flying kites and now that I was on the cusp of adolescence with the marriage market looming on the horizon, my mother was forced to take notice. She confronted “the problem” — as grave as a death sentence — and, with her characteristic can-do attitude, rolled up her sleeves, spat in her palms, and set out to find a solution.

By that time I had understood, as children usually do, that I did not quite come up to snuff. I also remember feeling terribly guilty for having failed my beautiful mother. Which is why, as a squatty ten-year old — still not fair but now also fat with the same round nose though no longer bald and redeemed somewhat by luxuriant, thick, black, waist-length hair — I participated in my mother’s whacky schemes to fix me for the future marriage market with the maniacal zeal typical of her. I went along, knowing deep in my heart that that she was in for a disappointment. Sure enough, my fat nose and dark complexion remained remarkably resistant to my mother’s mad though heroic ministrations.

She tried many things starting with starvation. I was to go without desserts, especially ice cream. One dry toast instead of the usual two at breakfast — and that too without butter or jam, an unbearable deprivation when everyone else had delicious homemade plum jam on buttered toasts — to “weaken the pigment making cells.” My mother came from three generations of doctors — her grandfather graduated from the King Edward Medical College in the late- nineteenth century, an uncle in the next generation, and two sisters in the following one — and presumed she knew all there was to know about human cells and their doings.

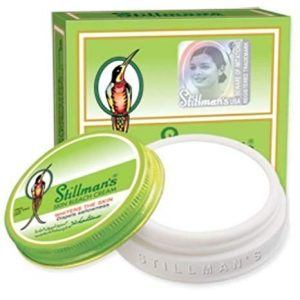

She tried home-made remedies — face masks of various herbs and unguents, mostly vile and foul smelling, the main ingredients being rotten eggs and sour yogurt — all to be applied during the hot and muggy afternoons of a Punjabi summer in a time of no air conditioning. When these did not work she would look around frantically for a miracle cure. One time she found an advertisement in “Women’s Day,” a magazine she subscribed to, for Stillman’s Bleach Cream — the sure cure for this worst of all afflictions. But where would she find Stillman’s Bleach Cream in sleepy old Sialkot so soon after the partition when everything was so chaotic? All Sialkot had was a vast cantonment and sports goods factories. It did not even have a sewer system (still doesn’t, though it supplies soccer balls for the World Cup). It did have, in early sixties, the most enchanting general store — Cheap Jack, the love of my unfair life — that sold lollipops and my beloved Illustrated Classics, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Ivanhoe, Green Mansions, the Lady in White, Treasure Island, and piles and piles of Tom and Jerry comics, all of which I consumed voraciously along with the lollipops. But no Stillman’s Bleach Cream.

Not one to be deterred, mom wrote to my aunt, her sister Gulshan, who at the time was doing a post-graduate diploma in pathology at Hammersmith Hospital in London. Of course Gulshan would arrange for the cream for she understood its critical importance having been in more or less the same situation herself. She was thirty years old and still unmarried wasn’t she? The women shook their heads again making sympathetic noises and ignoring the fact that Gulshan was Professor of Pathology at the only all-female medical college in the country and had won a Commonwealth Scholarship to study in UK. My aunt still had a year of studies to complete but since time was of the essence a colleague of hers on his way back was deputed to the task. Sure enough, half-a- dozen jars arrived two weeks later — as much time as it took for the ship to sail from Southampton through the Suez Canal and up the Arabian sea to arrive in Karachi from where they travelled by train to Lahore and then by GTS (Government Transport Service) bus to dopey Sialkot and into my mothers eager hands. Instantly she fell to the task in front of her.

The thick, greasy paste was applied diligently through endless muggy afternoons and hot and humid nights. But no miracle occurred — the women shook their heads and Baiji continued to hai, hai. Once, little brother, seeing me in distress, offered to share his buttered toast under the table and applied the cream to his face in solidarity. I felt a lot better though all he got was a resounding smack on the side of his head for wasting the precious commodity that had come all the way from England.

Along with the gooey thick Stillman’s cream on my face, I was to have a clothespin holding my nose all night in attempt to make it thinner. “You won’t even know once you are asleep and soon your nose will be perfect,” my mother reassured me. The clothespin was usually found on the floor in the mornings, much to my mother’s annoyance. Big brother, studying engineering at the time and trying to be helpful, offered his fancy stainless steel calipers to be used instead of the clothespin, which thrilled my mother, no end. This marvel of modern technology, also imported from England no less, was bound to hold and work.

I, my mother’s dutiful daughter, participated in this torture, praying for it to work for I too, like the rest of them, wanted her to succeed. I wanted so much for her efforts to produce the results that would make her happy — for her sake, not mine — for my condition did not bother me at all and if my mother had not gone into this frenzy it would not have occurred to me that there was anything wrong with me. I looked out to the world with enthusiasm, found it beautiful, and thought I was too.

Alas, nothing worked. Just as it seemed that I was doomed to being husbandless forever, who else saved me but the patron-saint of young women battling the slings and arrows of the marriage market — Jane Austen.

And that, dear reader is another story.