by Abigail Akavia

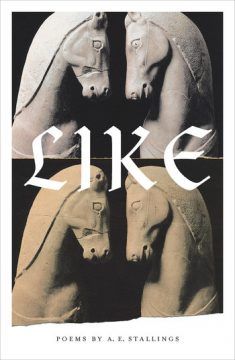

A. E. Stallings’ long poem “Lost and Found” (from her 2018 collection Like) delivers a mesmerizing meditation on loss in its various and myriad forms. I first encountered it read out loud, like a true epic, and I was gripped, astonished at once by the breadth of the journey Stallings invites us on as by the intimacy of its landscapes. A journey from the prosaic, to a Virgilian terrain of shadows and truths, and back again.

The protagonist of this journey is a poet-mother—can we just agree to call her Stallings?—who starts off on her hands and knees, crawling on the floor in search of a lost toy. In her dream that night, she is led by a woman—she later learns it is divine Mnemosyne herself, Memory, Mother of the Muses—on a guided tour through “the valley on the moon / Where everything misplaced on earth accrues, / And here all things are gathered that you lose.” I found it a delightfully feminist act on Stallings’ part, to cast herself as a hero who crosses the threshold between our world and the beyond, in order to come back to the land of bills and paperwork and lunches waiting to be packed for school, armed with wisdom. A journey that reveals and affirms her position in this mundane world as a poet, a “sieve” who lets the moments pass through her, an artist noticing and writing them down.

On this dream moonscape of loss, we follow Stallings from sightings of “orphaned socks” and “dropped pills” to physical spaces we can no longer access, rooms in our grandparents’ houses and “Love’s first apartments.” On we go to discover a barn filled with “the frayed, lost threads / Of conversations, arguments” (yes, I want to shout out, I knew it! They simply had to go somewhere), then to “the letters

We meant to write and didn’t—all the unsaid

Begrudged congratulations to our betters,

Condolences we owed the lately dead,

Love notes unsent—in love, we all are debtors—

Gratitude to teachers who penned in red

Corrections to our ignorant defenses,

Apologies kept close like confidences.

At first, she thinks these pages are lost poems, poems “that perish[ed] at the brink of being,” but her guide reassures her that those are not so many; instead we are confronted with all those other messages that remained unwritten.

This record of writing-debts has an especially arresting effect on me, in a poem full of moments that take my breath away in their precision, beauty and familiarity. It startles me with the permission it suggests, the legitimacy to mourn what should have been written but was not, instead of loathing the procrastination with which the gap between should have and was not is habitually cloaked—that is to say, permission to mourn instead of self-loathe. Compassion twinkles here, almost unobserved. The compassion of writing down without keeping, which is something of an oxymoron—a buddhist outlook on the world that somehow also embodies the Neoteric tension between perpetuity and frivolity—is it perhaps the same compassion the poet has toward herself with all her “losses”? Letting go of all that shall and must remain unwritten, all that is lost, to allow herself to write what is ultimately more urgent: her poetry.

Ten years ago, I spoke at my sister’s funeral. I remember speaking of deadlines. You were always better at it than me, I told her, you got your stuff done on time. I meant to read you this letter before you died, I said, to say farewell while you were still here. I didn’t make it, I told her then, when she was being buried.

It could not have been written in advance.

But every time I miss a deadline, every time a letter of condolences or apology or love remains unwritten in my mind until the period of its appropriate sending expires, a pang of loss tugs at me.

I should probably let that go.

***

Another unexpected appearance of mourning in the everyday, from Stallings’ Like.

The Stain

Remembers

Your embarrassment,

…

When over-served,

You misconstrued

And blurbed your heartsick

On your sleeve,

When everything

Became imbued

With sadness, yet

You couldn’t grieve.

Inalienable

As DNA,

Self-evident

As fingerprints,

It will not out

Although you spray

And presoak in the sink

And rinse:

What they suspect

The stain will know,

The stain records

What you forget.

If you wear it,

It will show;

If you wash it,

It will set.

Worse than stains are those moth-holes that appear in my sweaters. The little hungry butterflies’ life-traces mark the beginning of the end of the garment. It has become infected by your sweat, by crumbs, a toddler’s eager pawing. After all, sweaters are not underwear: you don’t simply toss them in the hamper after one day in contact with your skin. You cannot bunch them with the early morning load you mindlessly shove into the machine, getting a head start on this school-day’s list of chores before you have even turned on the kettle. But the moths, they will come. To guzzle the salt and fat you leave behind. Wool sweaters are now our corsets: you may not eat or move too briskly while you wear them. Your vitality will spoil them with imperfections.

No choice but to abstain from cashmere for life. This time I vow it. It’s not worth the heartache of inevitable disfiguration.

Ah, but have you learned nothing, my child? I hear my moon-mother lovingly admonish. Life is too short to mourn stuff. Yes, it is no doubt easier to wash a garment that has some man-made material weaved into it. But do not leave your sons only this very sound counsel, to choose practical clothes. Teach them also to pick the most silky-soft one to go dancing in. Teach them how to darn the holes. Teach them not to worry about the spills.

Ballet leotards soaked with sweat: underarm sweat, underboob sweat, sweat tracing the shape of my navel; if there are white stains on the leotard you can’t wear it again to class unless you start the pliés with an extra layer on, and by the time you peel that one off you have soaked the leotard again and the white doesn’t show.

That multi-tone purple button-down shirt I bought when I was sixteen years old, and wore till it tore more than sixteen years later, dutifully it served me even as it was demoted from “top five coolest things in my closet” to “convenient for breastfeeding but never to leave the house in.”

My armor, my corsets, skins I have shed.

How long will I remember you?

How long will I remember what I wore to my sister’s funeral? How long till the memory of the striped black-and-very-pale-pink boat-neck top fades? And the brick-red boots of hers that were a size too big and which I nonetheless wore for a year afterwards, until it no longer made sense, and I finally bequeathed them to a friend of hers whom they actually fit—will they remain unforgotten longer? How long till I cannot conjure the texture of the leather, the long strand that wrapped around my calve twice to secure each boot in place like a greave? Till I can no longer feel their weight on my feet (too small to fill them properly), nor recall the way they brightened up my outfits but pulled down on my bones. I willed myself to trudge on, though every time I took a step in the world it was too heavy.