by Emrys Westacott

“In unity is strength!” This is one of the foundational maxims repeated by progressive forces everywhere. As history has often demonstrated, though, unity is easier to affirm than to achieve. And the consequences of failing to achieve it can be dire.

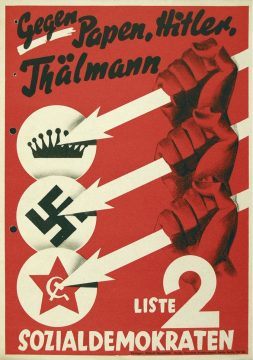

Germany 1932

The direst of all dire examples of progressive disunity helping to bring about a horrendous outcome was that which allowed Hitler to attain power in Germany in 1933. Here are the results of the November 1932 general election:

Nazi Party 33.1%

Social Democrat Party 20.4%

Communist Party 16.9%

Catholic Centre Party 12.4%

German National People’s Party 8.3%

Bavarian People’s party 3%

The Social Democrats and Communists combined received more votes than Hitler’s Nazis. But in the early 1930s, even though the threat posed by the Nazis was becoming increasingly dangerous and apparent, those opposed to them could not form a united front. The Social Democrat leadership viewed communists and fascists as essentially the same, and they chose to support the right-wing Hindenburg government as a “lesser evil” to (and as a bulwark against) Hitler. The communists labelled the Social Democrats “social fascists” and also rejected the idea of collaboration against the Nazis. In January 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor. Less than eight weeks later, Germany was a dictatorship. Many of those who couldn’t work together to oppose Hitler would soon find themselves suffering and dying together in Nazi concentration camps. Twelve years later, more than seventy million people lay dead, victims of World War II, and much of Europe lay in ruins.

Florida 200

A more recent example of disunity opening the way to disastrous consequences was the US presidential election in 2000. Democrat Al Gore won the popular vote, receiving over half a million more votes nationwide than Republican George W. Bush. But Bush eventually secured victory in the electoral college when the US Supreme Court halted a recount ordered by the Florida Supreme Court, leaving Bush the winner in Florida by 537 votes and hence also in the Electoral College.

Ralph Nader ran that year as the Green Party candidate for president, and in Florida received 97,488 votes. Had Gore received just one percent more of those votes than Bush, he would have become president. Many have blamed Nader for being a “spoiler” who helped Bush get elected. Nader and his defenders typically make two arguments:

- Gore and Bush were as bad as each other. Nader described them as Tweedledum and Tweedledee. Against those who argued that Gore was the lesser of two evils, he said: “If they keep settling for the lesser of two evils, at the end of the day there’s still evil.”

- Nader didn’t cause Gore to lose Florida, or the election. There were many other factors that were responsible, from Bill Clinton’s philandering (which tarnished his presidency and, by association, Gore) to Gore’s own weaknesses as a candidate, which resulted in him losing even his home state of Tennessee.

How good are these arguments? Let’s consider them in turn.

Without question, there is plenty for progressives to disagree with and be dissatisfied about when considering the political philosophy and policy record of “centrist” Democrats like Al Gore. Nader’s criticism of the Democratic leadership for failing to seriously oppose the dominant influence over politics wielded by corporate interests is thoroughly justified. But his view that it would make no difference whether Bush or Gore ended up in the White House is absurd.

Try telling that it made no difference to all those adversely affected by the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq ordered by George W. Bush under the influence of Dick Cheney and co. Exactly how many people died as a result of this illegal act of war is disputed, but even the most conservative estimate put it at over 100,000. In all probability it is much higher. In addition, one should also take into account all the people seriously injured, the grief experienced by the family and friends of those killed, and the long-term regional turmoil that the invasion precipitated or exacerbated, including civil war in Syria, and the displacement of millions who were rendered homeless and impoverished. Al Gore may have his faults. But it’s a reasonable assumption that he would not have responded to 9/11 by invading Iraq.

Or, to take just one other legacy of the Bush presidency, consider his Supreme Court nominations: John Roberts and Samuel Alito. Nader laments the influence of money in politics. But Roberts and Alito have consistently opposed campaign finance reform. For instance, they helped to provide the 5-4 majority opinion in the Citizens United case that opened the floodgates to unlimited spending by corporations on elections, a ruling which Nader said “shreds the fabric of our already weakened democracy by allowing corporations to more completely dominate our corrupted electoral process.” It’s reasonable to assume that had Gore been president he would not have nominated such ideologically committed conservatives to the Supreme Court.

While campaigning in 2000, Nader indicated several times that he thought it would be better if Bush became president. And he campaigned accordingly. In the last stages of the campaign, he didn’t focus on states like New York or California where he could hope to increase his vote without risking Bush a victory. Instead, he campaigned furiously in swing states like Florida.

Nader said that a Bush victory would be like “a cold shower for four years that would help the Democratic Party.”[1] But this seems to overlook the rather obvious fact that while the ‘cold shower’ is going on–and it lasted eight years, not four–all sorts of harm, much of it very long-term, was done to causes that Nader has championed throughout his life, including consumer protection; environmentalism; and the need for government regulation to curb corporate power.

What about the second argument cited above? It is, of course, perfectly true that there were many causal factors helping to determine the outcome of the election in Florida. But this is true of any event. My car ends up in a ditch. What was the cause? The icy road? The low quality tires? The vehicle design which makes for poor handling and long stopping distances? The deer that ran unexpectedly into the road? The fact that I was driving fast? The fact that I was driving drunk? Answer: all of the above.

Some of the causes cited are environmental conditions; some are triggering events; some are matters for which I may be held responsible. It’s perfectly true that if the road hadn’t been icy I wouldn’t have skidded into the ditch. But it’s also true that I wouldn’t have crashed if I hadn’t been driving so fast. How would you respond if I said that the accident was caused by the ice, not by my speed. You would surely, and very reasonably, say that I was trying to evade responsibility. I was aware of the environmental conditions and I should have driven accordingly. Similarly, Nader was fully aware of the electoral situation (the environmental conditions). Claiming that he was not responsible for Bush’s victory even though he actively campaigned as if he desired this outcome is analogous to me saying that my speed and my drinking had nothing to do with my crashing.

The election of Trump in 2016

Disunity among progressive forces has also been seen as a crucial factor in bring about the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Although Hilary Clinton received almost three million more votes than Trump nationwide, Trump won in the electoral college. This time Jill Stein was the presidential candidate of the Green Party. Three states in particular were very closely fought and proved decisive.

Pennsylvania: Trump beat Clinton by 44,296. (Green Party: 49,941)

Michigan: Trump beat Clinton by 10,704. (Green Party: 51,463)

Wisconsin: Trump beat Clinton by 22,748. (Green Party: 31,072)

It would be a misrepresentation, I think, to say that Jill Stein was just as responsible for Trump’s victory as Nader was for Bush’s. Of those who voted Green in Pennsylvania, even if none of them switched their allegiance to Trump, over eighty-nine percent would have had to vote for Clinton for her to win the state. Although one would expect Green voters to view Trump with extreme disfavour, it is likely that many of them take Nader’s attitude toward the two main parties and vote Green as a way of registering a protest against politics as usual. Nevertheless, one cannot help wondering what Green voters think when they read of Trump withdrawing from the Paris Agreement on climate change, of his appointing Andrew Wheeler, a former energy lobbyist, as head of the EPA, or of his rolling back over ninety federal environmental regulations. A joint statement by several environmentalist groups issued recently declared that “Donald Trump has been the worst president for our environment in history.[2] So the question remains: Why would someone inclined to vote Green not think it is worth trying to avoid this outcome?

It has also been argued that Bernie Sanders bears some responsibility for Clinton’s defeat. Clinton herself recently complained that Sanders should have stopped campaigning for the Democratic nomination sooner than he did, once it became clear that he couldn’t win, and that although Sanders eventually endorsed her, some of his supporters continued to attack her and to urge people not to vote for her right up to election day.[3]

It is very difficult to determine with any precision or certainty counterfactual claims such as, “If only Sanders had done X, Clinton would have won.” (This caveat about counterfactuals obviously applies also to what was said above about the effect of Jill Stein on the 2016 election.) Individuals vote the way they do for many different reasons. It certainly strikes me as strange that more than ten percent of Democrats who voted for the socialist Sanders in the primaries eventually voted for Trump. But the thinking behind voting behaviour is often opaque. It’s a mistake to assume that every registered Democrat is somewhat liberal, or that every Sanders supporter is somewhat left-wing.[4] It’s also possible that Sanders may have helped energize some Democratic voters and campaigners, thereby helping Clinton.

November 2020

Will a lack of unity among those opposed to Trump lead to him being reelected in 2020? I certainly hope not. At the same time, it’s hard not to grow anxious as the contest to determine the Democratic candidate heats up. On the whole, so far, the candidates have refrained from slinging too much mud at each other. What so often happens, though, is that as those in the lead get closer to the prize, and as those falling behind grow desperate, the mud that’s slung starts being the kind that sticks, giving ammunition to the enemy. The spectacle of disunity itself can also turn voters off.

America in 2020 is not Germany in 1932. But the total subservience of the Republican party to Trump, whose autocratic outlook and naked cynicism are so apparent, has many serious students of political history worried that the US could be about to lurch irreversibly towards author tarianism. Given how high the stakes are, everyone opposed to Trump and what he stands for should obviously make defeating him in November an absolute priority. This should surely outweigh concerns about ideological purity or any desire to register an independent protest.

When a ship is in danger of sinking, it’s all hands to the pumps. This ought to be the attitude of anyone who recognizes the danger posed by Trump and the current Republican party. Any other attitude is irresponsible. “In unity is strength” is one good maxim to keep in mind. So, too, is another piece of traditional wisdom: the enemy of the good is the perfect.

[1] Transcript: Ralph Nader on ‘Meet the Press.’ May 7, 2000.

[2] https://www.ecowatch.com/trump-worst-president-environment-2645034831.html

[3] https://thehill.com/homenews/campaign/480990-clinton-sanders-and-supporters-did-not-do-enough-to-unify-party-in-2016

[4] See Robert Wheel, “Did Bernie Sanders Cost Hilary Clinton the Presidency?” for a lucid discussion of how complicated such questions are.