by Jeroen Bouterse

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.

Mind you, I mean a proper skeptic, a Pyrrhonist or something. What attracts me is not this unsustainable Cartesian angst about maybe living in the Matrix, but the wholesome promise of the ancient skeptics: that if you can live with uncertainty, you unlock this treasury of psychological benefits. Suspension of judgment, not believing to know what you don’t know, supposedly allows you to level up intellectually: to be inquisitive and critical, to open your mind without your brain falling out. The ancient skeptics were smart and prescient about contrasting themselves to the ‘dogmatists’ – who wants to be a dogmatist anymore?

So what’s holding me back? Well, I’m ashamed to say that the first thing that comes to mind are those paradoxes. You know them. Does our skepticism extend to the truth of skepticism, and similar objections. Also, are we supposed to suspend judgment about the truth-value of identity-statements, tautologies or contradictions? And if not, don’t those simple tautologies bleed into more complicated analytical truths, or even into mathematics? I’m not sure. Do I have to have a clear-cut opinion on questions like these before I can, with conviction, call myself a skeptic – all the while maintaining my suspension-of-judgment? That is a difficult balancing act that sounds almost like work.

Even though I humbly admit that I don’t know enough about these issues, I fear that my very insecurity about them demonstrates that I don’t have the mind to be a skeptic. I’m afraid to be a dogmatist about any of these questions, because I’m afraid to be wrong. That’s a condition that can easily escalate into desiring to be right. The skeptic on the other hand, while interested in problems surrounding knowledge, somehow manages to see all of them as somebody else’s problems. Read more »

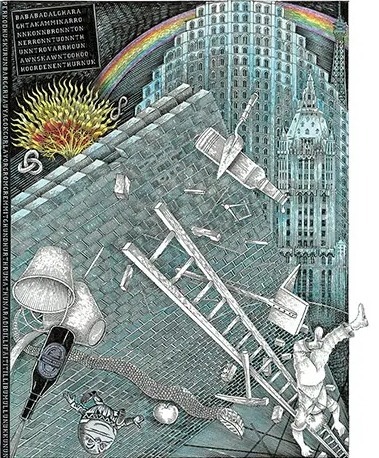

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story.

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story. One of the things that fascinates me about history is the different ways we know historical periods. We know the times we live through in a very deep way, not just the events and how they affect us, but the details of daily life. We know the slang, the jokes, the mid-list books; the forgettable songs and the ephemeral news; what the world smells like and how it tastes and sounds. It’s very hard to know another time period in anything like the detail we know our own: what people wore to work, what they did on Saturday afternoons, what all the machines did and why they were made.

One of the things that fascinates me about history is the different ways we know historical periods. We know the times we live through in a very deep way, not just the events and how they affect us, but the details of daily life. We know the slang, the jokes, the mid-list books; the forgettable songs and the ephemeral news; what the world smells like and how it tastes and sounds. It’s very hard to know another time period in anything like the detail we know our own: what people wore to work, what they did on Saturday afternoons, what all the machines did and why they were made.

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.