by Joan Harvey

At night you’d think

my house abandoned.

Come closer. You

can see and hear

the writing-paper

lines of light

and the voices of

my radio

Jerónimo’s House, Elizabeth Bishop

Don Quixote, and with him, of course, faithful Sancho Panza, inhabit my kitchen; primarily the space between the sink and the kitchen island. I listen to the tale of The Knight of the Sorrowful Face when I do the dishes and clean the counters and, as it is a very long book and I only spend around twenty minutes at a time doing these tasks, these two adventurers have been getting frightfully bashed up in my kitchen for months. While in other times I might have also listened on long car trips, I’m now programmed, when walking into that space, to immediately think of donkeys and basins and chivalry. At the moment I have only 17 hours 27 minutes and 56 seconds in the book left to go, but I suspect it will be even longer before my kitchen is free of knights errant and their faithful squires.

My Pavlovian response brings to mind that mnemomic device, the Memory Palace, in which you mentally put something you want to remember into a room in your house. To be honest I haven’t really tried this method, because I can never remember to use it when I need to remember something.

This is all to say that our houses are home not just to our bodies. Bodies are the condition of architecture, but the way in which our dwellings hold us, keep us warm, give us space and light (or lack thereof), also plays on our minds. Houses haunt us as much as we haunt them. And because during this virus most of us are home, most of the time, our relationship with our homes, with our houses (in French to be at home is to be at the house), comes to the forefront. Whether we’re alone in a tiny studio apartment, or with our three charming daughters and two charming dogs in a large house in the suburbs, or in a queer communal house in a small city, this place where we live and now rarely leave has come to have much more weight. We are aware of the homeless and hope that they are finding shelter as we do. And we might also grow aware that, with our heavy mortgages and loss of income, this shelter we’ve taken for granted is a somewhat precarious thing.

Czeslaw Milosz wrote that “the body always bears…the trace of the bearing, gestures, and posture imposed by the clothes commonly worn.” And in a slightly different way, the geometry of our first houses or apartments must shape our earliest perceptions. We move from our mother’s womb into some kind of shelter. Gradually our eyes make out the ceiling, eventually we crawl on the floors, discovering them tactilely with our whole bodies. Walls keep us from getting lost. And if there are stairs they are gated, until someone forgets. And then we learn to climb on them and fall on them.

Houses, unlike our spaces of work, shelter daydreaming, a state equated at times with sloth and idleness. Meditators must famously focus their minds, bring them back from those castles in the sky, but of course daydreaming has its own value. We dream of small rooms, because it is in small rooms (or corners of large rooms) that we can retreat to the privacy of our own minds. Even if we live in a large house we can still fantasize about a hermit’s hut as a place of privacy, escape, a place just to be, to get down to bare-boned existence, where we are reduced starkly to ourselves. We need a place to retreat, a room of one’s own. It’s difficult to find this in houses where many are crowded together, but when available, Gaston Bachelard reminds us in The Poetics of Space, “the passions simmer and resimmer in solitude: the passionate being prepares his explosions and his exploits in this solitude.”

Because of this desire to be alone with our passions, our solitudes, we read or buy or drool over picture books of cozy cabins and tiny houses (or we did until we found ourselves shut inside). Elizabeth Bishop even had a dream prison cell “about twelve or fifteen feet long by six feet wide.” She describes the door, the bed, even which side of the cell she sees the bed on. And “the walls I have in mind are interestingly stained, peeled, or otherwise disfigured; gray or whitewashed, bluish, yellowish, even green—but I only hope they are of no other color.” Obviously she spent quite a bit of time contemplating her ideal cell.

Most of us have, or have had, dream houses. Wittgenstein decided to design the perfect house for his sister, and he was so exacting that, because he was unhappy with the proportions, he had the ceilings taken out and raised by 30 mm. But, after this very elegant house was finished, his sister chose not to live in it. Bachelard warns us that it is the project of dreaming, not the finished house, that is essential. And of course one person’s dream is not another’s.

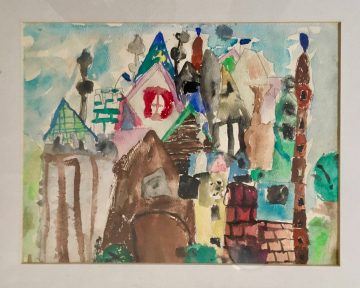

Speaking of sisters, as a child my sister had an assignment to paint a picture of a house she wanted to live in. She wanted to live in a castle and apparently thought towers and turrets the key to being comfortable, not to mention as many different building materials as possible. Her castle also contained plenty of places for privacy. My parents hung her painting up and this castle became my ideal house as well, though what I must have retained most was the lightness of it, and the color, things I’ve embraced in my current home.

Speaking of sisters, as a child my sister had an assignment to paint a picture of a house she wanted to live in. She wanted to live in a castle and apparently thought towers and turrets the key to being comfortable, not to mention as many different building materials as possible. Her castle also contained plenty of places for privacy. My parents hung her painting up and this castle became my ideal house as well, though what I must have retained most was the lightness of it, and the color, things I’ve embraced in my current home.

While the houses where we spent our childhood may haunt our sleeping dreams, I suspect that most of us have no desire to actually move back. But consciously or unconsciously we may reproduce something about our early experience in the places we currently live. My house does not resemble my childhood house, but does have a certain connection—as a child I looked up past the straight line of a bridge to mountains; now from a certain angle I look up past the straight line of a fence to mountains. There were aspen trees where I grew up, and none near my current house, so I planted some. Of course not everyone can or wants to reproduce their childhood. But we may notice how our current material circumstances may preserve elements of our actual childhood houses as well as our childhood dream houses.

For years I lived in a studio in New York, and a book of interiors I like to return to is of photos of people in their apartments in the Chelsea Hotel. “You smell people, passion,” one of the occupants says. “It is evident that artists have lived their problems here.” Vivian Gornick, a passionate New Yorker, writes that she lives sparely, because “stuff’ makes her nervous, while her friend lives in a space overflowing with things. Neither of them, she says, are at home in their apartments, but rather their home is on the street, and in street life. I feel for her, and so many others, now when that vivid exterior life is so diminished. But she also writes about the pleasure she gets at nights from lit windows all around her, “the anonymous ingathering of city dwellers. This swarm of human hives, also hanging anchored in space…” I suspect the nightly applause for health care workers helps counter enforced isolation.

On the other end of the spectrum from the hut, we learn from the play Buyer and Cellar that Barbara Streisand has put an actual row of pretend shops in her basement and has photographed them for a book. I confess to finding this oddly embarrassing; it is not beyond my imagination that someone with the means should wish to indulge herself this way as a means of displaying and enjoying her lovely things, but that she lets the world know of her at once secret and ostentatious vice, I find confusing.

Caves and cave men and earliest human habitations still have a large place in our imagination; it seems we’ve always given a good deal of thought to how we shelter. Alberti, writing in the middle of the fifteenth century, tells us how the grandmother’s room should be: “. . . in need of rest and quiet, [she] should have a bedroom that is warm, sheltered, and well away from the all the din coming from the family or outside; above all, her room should enjoy a little fireplace and other comforts of the body and soul, essential to the infirm.” How many grandmothers, once they are unable to live on their own, might dream of a place like this.

With RVs people become like turtles, taking their homes with them everywhere. I’ve never been drawn to that life—when I’m on the road I want to get away from my home, even a traveling one. But I like visiting houses that are museums, places that carry traces of past intimacy—the Freud Museum comes to mind, rich with carpets and ancient objects, and the couch on which so many secrets were shared. I also think of Dylan Thomas’s writing hut. Though I haven’t seen it, a photo made a great impression on me because crumpled papers had been left on the floor. Of course there are writers we associate with certain houses, Thoreau with his cabin, Heidegger his hut, or these days that we’re shut in, perhaps Emily Dickinson or Emily Brontë. The subject of architecture and literature is too vast to even begin to address here. Bachelard even imagines words as little houses, each with its own attic and cellar and common sense ground floor.

With RVs people become like turtles, taking their homes with them everywhere. I’ve never been drawn to that life—when I’m on the road I want to get away from my home, even a traveling one. But I like visiting houses that are museums, places that carry traces of past intimacy—the Freud Museum comes to mind, rich with carpets and ancient objects, and the couch on which so many secrets were shared. I also think of Dylan Thomas’s writing hut. Though I haven’t seen it, a photo made a great impression on me because crumpled papers had been left on the floor. Of course there are writers we associate with certain houses, Thoreau with his cabin, Heidegger his hut, or these days that we’re shut in, perhaps Emily Dickinson or Emily Brontë. The subject of architecture and literature is too vast to even begin to address here. Bachelard even imagines words as little houses, each with its own attic and cellar and common sense ground floor.

In our consideration of houses, we also fantasize about materials and shapes: hempcrete, bricks made of mushrooms, straw bales, domes. We like the idea of our buildings somehow growing out of the earth or being connected to the idea of the ocean, like those earthships in New Mexico or like Eileen Gray’s vision of house as a shell. Contrarily we may prefer brutalist architecture that lacks all sentimentality. And, even as we’re protected from the elements, we want to bring the outside in, filling up vases with flowers, or hanging photos of wild places, or just staring out the window. At night after inhaling lavender we listen to rain machines or ocean waves.

“There does not exist a real intimacy that is repellent,” Bachelard tells us, immediately bringing to mind the repellent spaces inhabited by a certain prominent orange person, the golden gilded sterile spaces we’ve seen of his home, the icy Christmas displays of his wife. Where is intimacy possible there? On the other hand, Bachelard writes, “Over-picturesqueness in a house can conceal its intimacy.” We also need space for our own distances, for our own psyches to have room before they can interact with others. In this time of quarantine we are forced into intimacy with ourselves. I suspect those protesting with their huge guns for the right to go out are afraid of staying inside and getting to know themselves. Unfortunately, perhaps even in spite of the virus, it is safer for those they live with that they vent their anger outside.

I clean the oven, the first time in years, and lo and behold, it is blue inside, not black as I had thought for the past decade. A friend waxes his furniture. We can do domestic work, remake our objects, put labor back into them, care for them. Keep our houses alive. Or, with this unabated dwelling, create more messes everywhere. I don’t know how parents who have to work at home and look after young children manage. Now that we live in them full time, we all inhabit our houses in different ways. A friend who was used to going to the gym buys weights, sets out a rowing machine in the sun, and is perfectly content. A dance student choreographs her dances in the bathtub and on the couch. I pace through my house, walking back and forth from my study to the kitchen to the sitting room (where no one ever sits except me), walking these paths so much I wonder that the wood floors aren’t grooved from my footsteps. I go into a different room to get away from myself or to sense myself in new ways. Just as different books or different people bring forth varying aspects of ourselves, so different rooms can do the same.

What we miss most now is the rhythm of leaving so that we can return. We think of animals in their burrows or nests, but they too emerge or are kicked out. Shy people are advised to come out of their shells. We like the concept of love nests, but we usually fly the nest when we can. Coming out of the closet, which often requires enormous courage, can allow one to experience fresh light and air and a happier sense of self. We reach out now on Zoom, but find that even there we’re confined in little boxes. But while we’re so contained it’s good to remember that there is also something strange and uncomfortable about wealthy resort towns of empty houses, where monster second or third homes, occupied only a few weeks a year, create a sense of vacancy and ghosts.

Our shelters protect us from the virus (and, where I live, from the packs of young mountain lions newly roaming the streets). So we try, as much as we’re able, to have interior adventures. To allow ourselves the luxury, if we can find a corner, for some daydreaming time. I was planning a marvelous trip for June, but was also anxious about booking the right flights and lodging and the cost. Of course now I’m not going, but when safe travel is available again I suspect I’ll focus more on how lucky I am to be able to move around the globe, and less on worry about the details. Meanwhile I have Quixote for vicarious adventure, and, as the wonderfully wacky George Meredith, whom I’ve had time to discover during lockdown, assures me:

“‘So you acknowledge that birds—things of nature—have their bad time?’

‘They profit ultimately by the deluge and the wreck. Nothing on earth is “tucked up” in perpetuity.’”

(fucked up in perpetuity?)

So we can hope.

(I owe the inspiration for this column to a wonderful Zoom discussion group on The Poetics of Space led by poet Zoe Tuck.)