by Raji Jayaraman

Audio Version

As a young and idealistic 21-year-old, I spent a year in India working with my hero, Jean Drèze. This was the mid-nineties. There were many idols to choose from. Nelson Mandela was universally worshipped. Even Bill Clinton had a following. Cool kids were building altars to Kurt Cobain, who had recently died by suicide. I suppose it says something about my social acumen that my hero was a pyjama-kurta clad Belgian who had renounced worldly possessions and lived in a Delhi slum. I say he “was” my hero not because he no longer is, but because he is no longer Belgian. He is the only European I know who has wanted, and successfully obtained, Indian citizenship. I’m Indian, but I think I can say without any self-loathing that only someone who is utterly committed to the cause would do that. He is often described as an economist activist. The oxymoron speaks for itself.

In order to afford one square meal a day and avoid having to room with Jean in his basti, I got a day job in the World Bank’s Delhi office. Bretton Woods Institutions, for all their post-modern capitalist swagger, have a strangely missionary zeal in their quest to save the world’s poor. Their employees—including my parents who worked for the UN for decades—regularly go “on mission” to developing countries, and they say that with a completely straight face. In the first month I was there, we had our first mission from Washington which, after a debriefing and reception in Delhi, was going to head to “the field”—a turn of phrase that rhymes with “mission” in all but rhyme.

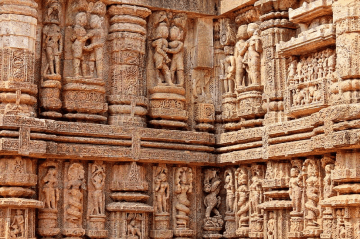

Over the last few decades, numerous Indian states and cities in the field have been re-christened, mostly because the British romped around the planet mispronouncing names and then spelling them accordingly. I’ve spent a long time trying to decide whether their misspellings are a mark of a. carelessness, b. arrogance, or c. disrespect. My best guess is d. all of the above. Take the names of Indian indentured labourers to the Caribbean, for instance. V.S. Naipaul is clearly just an anglicization of Naipal because as his grandfather was being herded off the boat, the guy in the safari suit and sola topee at the bottom of the gang plank repeated, “Nai-Paul” when grandpa said “Naipal”, because….Well, because “Pal” isn’t a name and “Paul” is, and that just made more sense to write down in a name ledger. Correct answer: d. Read more »

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a  In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms.

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms. I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil.

I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil. Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.