by Raji Jayaraman

Audio Version

As a young and idealistic 21-year-old, I spent a year in India working with my hero, Jean Drèze. This was the mid-nineties. There were many idols to choose from. Nelson Mandela was universally worshipped. Even Bill Clinton had a following. Cool kids were building altars to Kurt Cobain, who had recently died by suicide. I suppose it says something about my social acumen that my hero was a pyjama-kurta clad Belgian who had renounced worldly possessions and lived in a Delhi slum. I say he “was” my hero not because he no longer is, but because he is no longer Belgian. He is the only European I know who has wanted, and successfully obtained, Indian citizenship. I’m Indian, but I think I can say without any self-loathing that only someone who is utterly committed to the cause would do that. He is often described as an economist activist. The oxymoron speaks for itself.

In order to afford one square meal a day and avoid having to room with Jean in his basti, I got a day job in the World Bank’s Delhi office. Bretton Woods Institutions, for all their post-modern capitalist swagger, have a strangely missionary zeal in their quest to save the world’s poor. Their employees—including my parents who worked for the UN for decades—regularly go “on mission” to developing countries, and they say that with a completely straight face. In the first month I was there, we had our first mission from Washington which, after a debriefing and reception in Delhi, was going to head to “the field”—a turn of phrase that rhymes with “mission” in all but rhyme.

Over the last few decades, numerous Indian states and cities in the field have been re-christened, mostly because the British romped around the planet mispronouncing names and then spelling them accordingly. I’ve spent a long time trying to decide whether their misspellings are a mark of a. carelessness, b. arrogance, or c. disrespect. My best guess is d. all of the above. Take the names of Indian indentured labourers to the Caribbean, for instance. V.S. Naipaul is clearly just an anglicization of Naipal because as his grandfather was being herded off the boat, the guy in the safari suit and sola topee at the bottom of the gang plank repeated, “Nai-Paul” when grandpa said “Naipal”, because….Well, because “Pal” isn’t a name and “Paul” is, and that just made more sense to write down in a name ledger. Correct answer: d.

Another example. The surname of my best friend in university, also from Trinidad, is Seeterram. Seeterram is probably just careless, maybe a bit arrogant, but it borders on disrespect when you realize that the name should be “Seethā”-“rām”, which is a verbal marriage of the couple from the Ramayana, a Hindu epic whose protagonists are the beautiful, blameless Princess Seetha and the seventh avatar of the God Vishnu, Prince Rām. Again, it may have been deliberate, it probably was inadvertent, but my answer remains d.

In India, some name changes just reflect better Latin spelling of the vernacular pronunciation. For example, Calcutta was not so much renamed as correctly spelled, Kolkata, which is how you say it in Bengali. Others had more to do with tradition than British dysgraphia. Bombay was renamed Mumbai after a local deity, Mumbadevi. Chennai got its new name because, although the East India Company founded the city of Madras, locals had always called it Chennaipattinam.

The state of Orissa is now called Odisha and, as far as I can tell, this is because the letter “r” does not exist in the Oriya language. I don’t speak Oriya myself, so this claim rests exclusively on the fact that the name of the language has also been changed to “Odia”. I rest my case. Many Oriyans…Sorry, Odians, also cannot pronounce the letter “z”. It comes out like a “j”. So, for example, as anyone who has been to North India will attest, “zero” becomes “jero”.

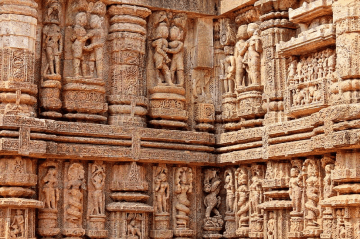

Back to the World Bank’s Delhi office. The mission arrived, comprising several middle-aged, white men. They wore their self-imposed uniforms of half-sleeved white pressed shirts with undershirts peeking over the top, and khaki high-waist pants with pleats and the inexplicable ankle fold. First stop: debriefing from Bank staff “stationed”—sometimes “posted”, never “living”—in Delhi. Next stop: reception with local officials. At this reception, two of them were cornered by an exuberantly charming minister from the state formerly known as Orissa, where the mission was headed shortly. Both Bank officials were economists of some standing, and both were religious: one, Jewish and the other, Mormon. The minister was extolling the virtues of his state, which is truly beautiful but is still, to this day, described without injury or insult by the rest of the country as “backward”.

He started with the golden beaches, and quickly moved on to the temples. “Oh the temples!” he gushed. “So beautiful the ahkitekcheh. So lowely the skulpches.” Here, he paused and sighed wistfully, “The bdests!” He cupped an imaginary pair of coconuts in his hands. “Puhfect! And the poses: from abow and below, standing and splitting. None of your mishnady style.” The Mormon economist’s face flushed. I thought he might faint. But that would have been impolite and, besides, the minister wasn’t quite done yet. “Bhubaneswar”, he added informatively, “is the capital city. When you come, you must pay a visit to the Jew. Beautiful Jew!” I caught my breath and looked anxiously at the second economist. His jaw had dropped and his skin had turned to chalk. It was only when the minister continued, at some length, to praise the mane of the lion and stripes of the jebra that the colour returned to his face.