by Paul Orlando

I’ve been exploring ways that tech innovation could lead to inevitable outcomes. Here’s a continuation of that, specific to the enduring human need for music.

Music has been around as long as there have been people. Longer if you count music made by animals. It’s safe to say that music will be a part of this world as long as there is life. So what happens when new technology encounters an eternal constant for humans?

Demand for something like music is built into what it means to be human. Music related tech development (especially if it is more about improvements rather than step changes) can be somewhat predictable. I use the term inevitable because we’re combining enduring human needs with forces that are largely about laws of physics applied to manufacturing. Supporting business models form.

Early Tech

Let’s look at some of the changes over the 20th century of the music industry. Treat this as a thought experiment on applying second-order thinking.

If you were born in 1900, in the early years of the recording industry, it’s likely that all of the music you heard growing up would be live music. An informal local band, or a more formal chamber orchestra, or singing in the home. You also would have been a child when Enrico Caruso recorded these versions of “Vesti la Giubba,” from the opera Pagliacci (which premiered in 1892).

Enrico Caruso – Vesti la Giubbia, first decade of 1900s

Caruso was one of the first international stars, both because he was a great tenor and also because his career coincided with the development of the early recording industry. His combined “Vesti la Giubba,” recordings are counted as the first million unit record sale in the US. (A bigger deal back then with one-quarter of today’s population and less disposable income.) Read more »

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us.

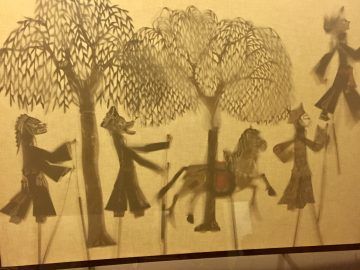

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us. When the Rajah’s barber could no longer keep the secret, he was seen darting by the sparrow in the tamarind, by the flinty owl in the giant oak that was surely a jinn’s abode, by a flock of hill mynahs flying through the buttery light of early spring. What was it that sent him bumbling through the jungle like that? Hours before, he had met the Rajah’s terrible gaze in the mirror when he discovered two sickle-shaped horns under his hair. This secret was as a rock he had swallowed, a rock he needed to expel. He was found panting by the fox of the jungle’s dank center, by a tightly knotted vine clutching a forgotten well. He saw that the well was old and there was bamboo growing in it. He saw it was safe and he screamed his fullest scream into the well: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret and happily soaked it up, but the next day it was cut down by a flute maker who had been in search of just the right bamboo. Soon, all his fine bamboo flutes were sold. Then, all the new flutes of Jaunpur sang out the secret: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret. The hapless barber had poured into it his last song.

When the Rajah’s barber could no longer keep the secret, he was seen darting by the sparrow in the tamarind, by the flinty owl in the giant oak that was surely a jinn’s abode, by a flock of hill mynahs flying through the buttery light of early spring. What was it that sent him bumbling through the jungle like that? Hours before, he had met the Rajah’s terrible gaze in the mirror when he discovered two sickle-shaped horns under his hair. This secret was as a rock he had swallowed, a rock he needed to expel. He was found panting by the fox of the jungle’s dank center, by a tightly knotted vine clutching a forgotten well. He saw that the well was old and there was bamboo growing in it. He saw it was safe and he screamed his fullest scream into the well: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret and happily soaked it up, but the next day it was cut down by a flute maker who had been in search of just the right bamboo. Soon, all his fine bamboo flutes were sold. Then, all the new flutes of Jaunpur sang out the secret: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret. The hapless barber had poured into it his last song.

Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”).

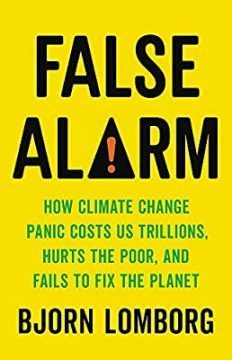

Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”). Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.

Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.

In one sense, the stories of the collection Almost No Memory, originally published in 1997 and reprinted in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis in 2009, can be read as a psychological portrait of a middle-aged woman coming to terms with all the usual things life has to offer after a certain age: the convolutions of domestic discord, shrinking horizons, the sobering insight that very little can change us anymore. The voices are both many and one, converging in a polyphony of percipient anxiety and resignation: we hear “wife one,” an “often raging though now quiet woman” eating dinner alone after talking on the phone to “wife two”; a professor who fantasizes about marrying a cowboy, although she is “so used to the companionship of [her] husband by now that if I were to marry a cowboy I would want to take him with me”; and a woman who “fell in love with a man who had been dead a number of years.” There is also a woman who “comes running out of the house with her face white and her overcoat flapping wildly,” crying “emergency, emergency”; a woman who wishes she had a second chance to learn from her mistakes; and one who has “no choice but to continue to proceed as if I know altogether what I am, though I may also try to guess, from time to time, just what it is that others know that I do not know.” The list continues, from a woman wondering why she can become so vicious with her children to another whose mind wanders to sex at the sight of “anything pounding, anything stroking; anything bolt upright, anything horizontal and gaping” and one who is filled with “ill will toward one I think I should love, ill will toward myself, and discouragement over the work I think I should be doing.”

In one sense, the stories of the collection Almost No Memory, originally published in 1997 and reprinted in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis in 2009, can be read as a psychological portrait of a middle-aged woman coming to terms with all the usual things life has to offer after a certain age: the convolutions of domestic discord, shrinking horizons, the sobering insight that very little can change us anymore. The voices are both many and one, converging in a polyphony of percipient anxiety and resignation: we hear “wife one,” an “often raging though now quiet woman” eating dinner alone after talking on the phone to “wife two”; a professor who fantasizes about marrying a cowboy, although she is “so used to the companionship of [her] husband by now that if I were to marry a cowboy I would want to take him with me”; and a woman who “fell in love with a man who had been dead a number of years.” There is also a woman who “comes running out of the house with her face white and her overcoat flapping wildly,” crying “emergency, emergency”; a woman who wishes she had a second chance to learn from her mistakes; and one who has “no choice but to continue to proceed as if I know altogether what I am, though I may also try to guess, from time to time, just what it is that others know that I do not know.” The list continues, from a woman wondering why she can become so vicious with her children to another whose mind wanders to sex at the sight of “anything pounding, anything stroking; anything bolt upright, anything horizontal and gaping” and one who is filled with “ill will toward one I think I should love, ill will toward myself, and discouragement over the work I think I should be doing.” Undoubtedly many insights and lessons can be drawn and will be drawn for a long time to come from the current worldwide covid19 epidemic; insights, for example, about the responsibility of politicians in the managing of health crises, about the importance of human cooperation both locally and internationally, about the vulnerability of the global economy to disturbances in the regular flow of people and commodities, about the crucial yet contentious role of the various media in the dissemination of information, etc. But here I am interested in focusing briefly on related issues regarding the problematic relationship of science and the general public. Specifically, I want to offer some reflections on why I think science in trying times can be hard to live with.

Undoubtedly many insights and lessons can be drawn and will be drawn for a long time to come from the current worldwide covid19 epidemic; insights, for example, about the responsibility of politicians in the managing of health crises, about the importance of human cooperation both locally and internationally, about the vulnerability of the global economy to disturbances in the regular flow of people and commodities, about the crucial yet contentious role of the various media in the dissemination of information, etc. But here I am interested in focusing briefly on related issues regarding the problematic relationship of science and the general public. Specifically, I want to offer some reflections on why I think science in trying times can be hard to live with.