by Lawrence Blume and Raji Jayaraman

The United States is undergoing a long-overdue reckoning, in the highest echelons of government, with the problem of systemic racism. The new Biden-Harris administration has declared that “The moment has come for our nation to deal with systemic racism…” The wide span of policy remedies it goes on to propose reflects the breadth of the problem. A further challenge is that systemic racism runs deep, operating not only at the level of interpersonal interactions but from the workings of our social systems. It may be sustained by formal structures such laws or rules, in which case an obvious remedy is to reform those structures. But it can equally be sustained by amorphous structures that are harder to combat.

The United States is undergoing a long-overdue reckoning, in the highest echelons of government, with the problem of systemic racism. The new Biden-Harris administration has declared that “The moment has come for our nation to deal with systemic racism…” The wide span of policy remedies it goes on to propose reflects the breadth of the problem. A further challenge is that systemic racism runs deep, operating not only at the level of interpersonal interactions but from the workings of our social systems. It may be sustained by formal structures such laws or rules, in which case an obvious remedy is to reform those structures. But it can equally be sustained by amorphous structures that are harder to combat.

One of the most insidious mechanisms through which systemic racism can be sustained is the vicious circle of self-fulfilling beliefs. Here is the idea. Suppose there are two groups, Blacks and Whites. Blacks hold beliefs about Whites, and Whites hold beliefs about Blacks. They interact with each other, choosing behaviours based on their beliefs. Everybody’s beliefs are validated by the behaviours they see.

We say that these beliefs are “in equilibrium” because each group’s belief enables the other. The representation each group holds about the other is correct because and only because each group holds these representations. When a large number of individuals in a market or some other social structure interact—and this is where the “systemic” part of racism enters—the beliefs turn into a self-fulfilling prophesy. Positive, “pro-social”, behaviours in this context are sustained by positive beliefs, resulting in a virtuous circle. Negative, “anti-social”, behaviours are sustained by negative beliefs, resulting in a vicious circle.

In his brilliant book, An American Dilemma, Gunnar Myrdal saw racial disparities in the United States in precisely this light. “White prejudice and discrimination”, he writes, “keep the Negro low in standards of living, health, education, manners and morals. This, in its turn, gives support to White prejudice. White prejudice and Negro standards thus mutually ‘cause’ each other.” While Myrdal implicated deliberate discrimination in this process, subsequent work by Kenneth Arrow and others has taught us that the vicious circle operating in systems with no deliberate prejudice, can still generate discriminatory outcomes.

How does this happen? Read more »

1.

1.

Look on the back label of most wine bottles and you will find a tasting note that reads like a fruit basket—a list of various fruit aromas along with a few herb and oak-derived aromas that consumers are likely to find with some more or less dedicated sniffing. You will find a more extensive list of aromas if you visit the winery’s website and find the winemaker’s notes or read wine reviews published in wine magazines or online.

Look on the back label of most wine bottles and you will find a tasting note that reads like a fruit basket—a list of various fruit aromas along with a few herb and oak-derived aromas that consumers are likely to find with some more or less dedicated sniffing. You will find a more extensive list of aromas if you visit the winery’s website and find the winemaker’s notes or read wine reviews published in wine magazines or online. In a recent article in

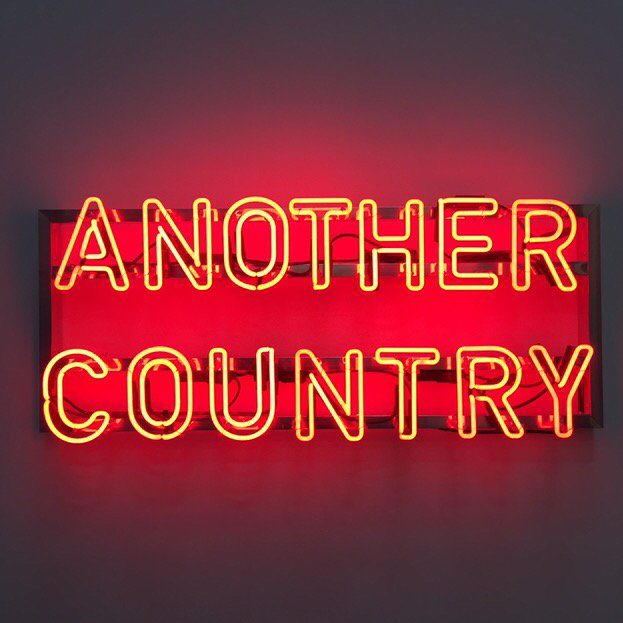

In a recent article in  High in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of northern Colombia, the Kogi people peaceably live and farm. Having isolated themselves in nearly inaccessible mountain hamlets for five hundred years, the Kogi retain the dubious distinction of being the only intact, pre-Columbian civilization in South America. As such, they are also rare representatives of a sustainable farming way of life that persists until the modern era. Yet, more than four decades ago, even they noticed that their highland climate was changing. The trees and grasses that grew around their mountain redoubt, the numbers and kinds of animals they saw, the sizes of lakes and glaciers, the flows of rivers—everything was changing. The Kogi, who refer to themselves as Elder Brother and understand themselves to be custodians of our planet, felt they must warn the world. So in the late 1980s, they sent an emissary to contact the documentary filmmaker, Alan Ereira of the BBC—one of the few people they’d previously met from the outside world. In the resulting film,

High in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of northern Colombia, the Kogi people peaceably live and farm. Having isolated themselves in nearly inaccessible mountain hamlets for five hundred years, the Kogi retain the dubious distinction of being the only intact, pre-Columbian civilization in South America. As such, they are also rare representatives of a sustainable farming way of life that persists until the modern era. Yet, more than four decades ago, even they noticed that their highland climate was changing. The trees and grasses that grew around their mountain redoubt, the numbers and kinds of animals they saw, the sizes of lakes and glaciers, the flows of rivers—everything was changing. The Kogi, who refer to themselves as Elder Brother and understand themselves to be custodians of our planet, felt they must warn the world. So in the late 1980s, they sent an emissary to contact the documentary filmmaker, Alan Ereira of the BBC—one of the few people they’d previously met from the outside world. In the resulting film,

People are basically good.

People are basically good. Here’s an interesting game. You receive 20 dollars, and you and three others can anonymously contribute any portion of this amount to a public pool. The amount of money in this pool is then multiplied by 1.5 and divided equally among all players. Repeat 10 times, then go home with your money. What will happen? How much would you contribute in round one, if you knew nothing about your fellow players?

Here’s an interesting game. You receive 20 dollars, and you and three others can anonymously contribute any portion of this amount to a public pool. The amount of money in this pool is then multiplied by 1.5 and divided equally among all players. Repeat 10 times, then go home with your money. What will happen? How much would you contribute in round one, if you knew nothing about your fellow players?