by Jackson Arn

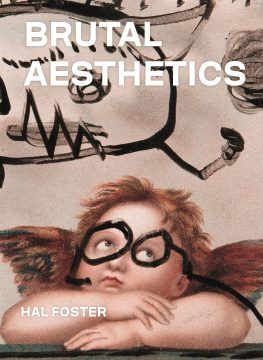

Brutal Aesthetics, the second volume of art criticism by Hal Foster to come out this year, begins at the close of World War Two, when the human race was fine-tuning some clever new ways of killing itself. Nuclear war; totalitarianism; genocide on an industrial scale; the gnawing despair of living with all this—for an era that saw so many unprecedented threats to our species, we’d have to wait until … well, you know.

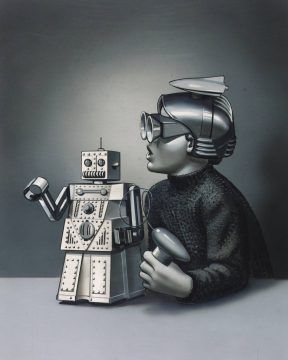

It was during these carefree days that five pioneers—Jean Dubuffet, Georges Bataille, Asger Jorn, Klaus Paolizzi, and Claes Oldenburg—developed an aesthetic of the brutal, the raw, the wild, the half-formed, the Dionysian, and the animalistic. “Positive barbarism,” Foster calls it, though the term has a neatness his subjects scorned. There is a family resemblance between Dubuffet’s bug-eyed “child art” and Jorn’s grinning monsters, Oldenburg’s ray guns and Paolizzi’s robots—and they all look something like the prehistoric cave paintings Bataille admired. For Foster, these resemblances suggest a deeper connection: five postwar westerners who were bold or daft enough to believe they could wriggle away from civilization.

You can’t be a 21st-century art historian and use the B-word without mentioning the Critical Theory Gods, AKA Adorno and Benjamin; that Foster does so is a mark of his book’s ambition. Positive barbarism isn’t the kind Benjamin had in mind when he wrote, “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” Nor is it the barbarism of Adorno’s “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” What emerges from Brutal Aesthetics instead is barbarism as a form of creative destruction. Foster wants his quintet to reject the facile humanism of the West but build, or at least hint at, a new, tougher version, moving past the rubble of civilization without forgetting it entirely. He wants them to “begin again.”

Already the contradictions are piling up: Is it really possible to begin again? And what kinds of barbarians have missions, anyway? Such is the quixotic challenge the barbarians—and Foster—take on: to make a style out of not having one. A few times, we’re reminded that Dubuffet defined art brut as the art “that doesn’t know its name,” an apt summary of the paradox. In order to unlearn his artistic training, Dubuffet sought inspiration in a host of outsiders: the young, the mentally ill, the indigent. When he felt he’d mastered an outsider’s style, it meant that the style had grown too codified, too predictable, too “inside”—in other words, that it was time to move on to something else.

Already the contradictions are piling up: Is it really possible to begin again? And what kinds of barbarians have missions, anyway? Such is the quixotic challenge the barbarians—and Foster—take on: to make a style out of not having one. A few times, we’re reminded that Dubuffet defined art brut as the art “that doesn’t know its name,” an apt summary of the paradox. In order to unlearn his artistic training, Dubuffet sought inspiration in a host of outsiders: the young, the mentally ill, the indigent. When he felt he’d mastered an outsider’s style, it meant that the style had grown too codified, too predictable, too “inside”—in other words, that it was time to move on to something else.

This might sound unpleasantly familiar: an elite European, preying on those too weak to protest, draining them of their life-force, converting it into prestige and generally playing the vampire. That Hal Foster, of all people, should write admiringly of Dubuffet may be regarded as a bit of a swerve, like Bob Dylan going electric or Michael Jordan batting for the White Sox. I still remember frowning over a photocopy of Foster’s essay “The ‘Primitive Unconscious’ of Modern Art” in college, and a strong argument could be (and has been) made that Dubuffet followed the primitivist playbook to the letter: first, celebrate, in a limiting, self-serving way, the artless art of marginalized groups; then, display that art to great acclaim in museums around the world. Dubuffet “did manipulate art brut for his own ends,” Foster allows— but perhaps this isn’t the fatal flaw some have made it out to be: “Rather than invalidate the brut … this ambiguity … might be central to its operation; it is what gives the brut its edge.” Both here and throughout Brutal Aesthetics, positive barbarism is an inconsistent framework—but who’d be foolish enough to expect consistency from barbarians?

Onward they march. By the time we arrive at the final chapter, on Claes Oldenburg’s sculptures, a number of brutal motifs have come into focus. These artists are always making people look like animals, and vice versa (“the creaturely” is Foster’s term for the in-between state)—consider Asger Jorn’s Interplanetary Woman (1953), or the paleolithic “Bird Man,” admired by Bataille. There is also, we can’t help but notice, an awful lot of shit in their artworks, from the thick brown impasto of Dubuffet’s canvases to the hard-soft turd of Oldenburg’s giant toothpaste tube, which Foster insists on linking back to anal eroticism.

But an erotics of art this book is decidedly not. Maybe it’s pointless to criticize an art historian for being too systematic—still, I can’t remember a great humorist being taxonomized as tiringly as Claes Oldenburg is in these pages. Oldenburg’s art, you see, is an ongoing study of “regression to the oral and the anal”—a thesis which taught me a good deal about regression to the oral and the anal but somewhat less about Oldenburg than I would have liked. A good rule of thumb: when reading academic art criticism, beware of sudden upticks in the number of rhetorical questions. When we arrive at the Oldenburg chapter, we get, “Might this monomania of similitude be a recurrence of the psychasthenic dissolution already glimpsed in The Street?” and then (on the same page!), “Might this annihilation/illumination be a magical attempt to trope the ‘creative destruction’ associated with capitalist transformation, or to commandeer the corrosive abstraction at the heart of capitalist exchange?” Yes? No? What? As the first of these tasty morsels suggests, Foster performs his reading under the sign of the Viennese witch doctor—if we’re to trust Brutal Aesthetics, Oldenburg did nothing but read psychoanalysis and convert it into sculpture.

It’s true that Oldenburg knew his Freud; his own writing is filled with psychoanalytic flourishes—e.g., “My art . . . strives for a simultaneous presentation of contraries.” But this isn’t quite the Freud Foster has in mind. His hopes for Oldenburg are a couple skyscrapers higher. He wants Oldenburg’s sculptures to undo oppositions instead of merely presenting them. He wants Oldenburg to liberate the viewer from repression instead of merely milking repression for laughs—and this is where the cracks in his category start to show. Foster makes his positive barbarians more positive than barbaric; he puts up with crudities and contradictions only when they can be rebranded as maneuvers in a noble political struggle. The result is that he takes all the tension, the wit, and (since we’re dealing with vulgar bodily functions) the piss out of modern art.

It’s a sign of Foster’s militancy that he seems ready to surrender as Brutal Aesthetics draws to a close. As he sees it, Oldenburg waged war on “the dark forces of capitalism” and lost:

This is an abrupt way to suggest that the historical conditions that prompted positive barbarism had changed, that brutal aesthetics was no match for the society of spectacle … I had hoped to conclude on a high note with Oldenburg, or at least on a light one given that he is one of the great comic artists, but he is also a realist. His art, his time—our time—does not allow a redemptive last word.

But artists aren’t political crusaders, thank god. They may take sides, but they never quite win, which means they never lose, either. When asked about his early career, Foster admitted, “I drank the apocalyptic Kool-Aid.” Maybe there are a few drops left in his veins? He treats the tyranny of the society of the spectacle as if it were a fait accompli instead of a handful of twenty-something programmers sitting in an open-plan office in Palo Alto. There is, whether Foster admits it or not, as much of a need for brutal aesthetics in the early 21st century, with its shiny surfaces and shambles of infrastructure, as there was in the middle of the 20th. No last word for us—just another snarl, another wreck, another rough beast that cannot be born or die.