by Raji Jayaraman and Peter N Burns*

We both have daughters who are good at math, but opted out of advanced math. In so doing, they effectively closed off entry into math-intensive fields of study at university such as physics, engineering, economics, and computer science. They used to be enthusiastic about math, but as early as grade three this enthusiasm waned, and they weren’t alone. It was a pattern we observed repeatedly in their female friends during those early school years, as boys slowly inched ahead.

We both have daughters who are good at math, but opted out of advanced math. In so doing, they effectively closed off entry into math-intensive fields of study at university such as physics, engineering, economics, and computer science. They used to be enthusiastic about math, but as early as grade three this enthusiasm waned, and they weren’t alone. It was a pattern we observed repeatedly in their female friends during those early school years, as boys slowly inched ahead.

This turns out to be something of a statistical regularity. Girls don’t start school hating math or doing worse at it than boys. Then, somewhere in elementary school, this changes for many girls and in some (though not all) countries, a gender gap in math performance appears. The reasons why girls sometimes begin to dislike or slip behind in math are important, wide-ranging and controversial, with scientists, psychologists, sociologists, and others all weighing in. What often starts as small fissure in test performance in childhood seems to be locked in by the onset of puberty. At this stage kids hit high school where they get to choose their subjects, and the great divergence is set in motion. Girls disproportionately opt out of math-intensive subjects. From there, there’s really no turning back. Girls tend to study subjects, and graduate with degrees in fields, that have lower math requirements. In the U.S., women receive only about a quarter of bachelor’s degrees in physics, engineering and computer science; the pattern persists in graduate school. That there are tragically few women in these professions, is a logical consequence.

What is remarkable about this great divergence is that the size of the initial gender gap in average math performance is itself, pretty unremarkable—typically under a quarter of a standard deviation depending on the country. In fact, in many countries, girls do at least as well as boys on average, and girls are well represented in the top tail of the math performance distribution. In short, girls do well in math by many metrics, both in absolute terms and relative to boys, and yet they opt out of math. Why is that? Read more »

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

The disappointing new film

The disappointing new film  Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us.

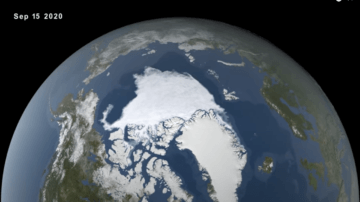

Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us. In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic

In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

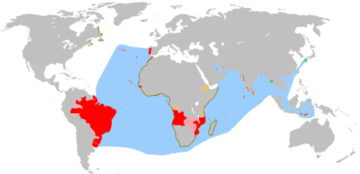

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?” The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.