by Emrys Westacott

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

The fact that sloth was counted by the Catholic church as one of the seven deadly sins back in the 6th century suggests that it is, at the very least, a widespread trait that we all need to vigilantly oppose. Samuel Johnson, writing about the varieties of idleness in The Idler (where else?), considers it perhaps the most common vice of all, more widespread even than pride. “Every man,” he writes, “is, or hopes to be, an Idler.” According to Voltaire, “all men are born with [among other things] ….much taste for idleness.” Consequently, “the farm labourer and the worker need to be kept in a state of necessity in order to work.” And Adam Smith famously observes that “it is in the interest of every man to live as much at his ease as he can” (although “ease” here could perhaps be interpreted to mean comfortably rather than idly).

Some recent scientific research that analyses the way people walk, run, and move around is said to support the notion that an instinct for avoiding unnecessary effort runs deep. It’s presumably the same instinct that causes people to spend two minutes driving around a parking lot looking for a space that will reduce their walk to the store entrance by thirty seconds. To the impatient passenger, this habit can be most annoying. But it has a plausible evolutionary explanation. Finding enough food to survive by means of hunting and gathering can use up many calories, so we are naturally programmed to conserve energy whenever we can. Read more »

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

The disappointing new film

The disappointing new film  Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us.

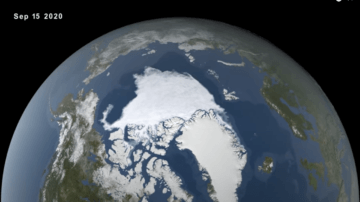

Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us. In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic

In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

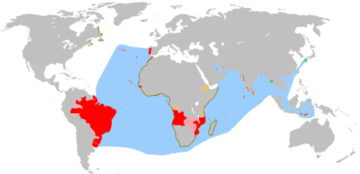

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?” The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (