by Dave Maier

One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

One reason is that when push comes to shove, or even before that, we simply follow traditional philosophical practice by providing arguments to show that we are right and they are wrong, thus construing the differences among our views as constituting differences in belief rather than, for example, the practical differences between different tools or perspectives. It is as if we have internalized the traditional criticisms: that we have abandoned objective truth and the objective world it represents in favor of our own subjective purposes. No, we say, watch us talk among ourselves! We care about truth just as much as you! Phenomenology is false and pragmatism is true, as my fully rigorous and entirely professional argument shows! Assent is required, on pain of irrationality!

Even when we’re not fighting among ourselves in this way, that same metaphilosophical ideal can still cause trouble. For instance, I have chosen to present my particular brand of anti-Cartesianism as a characteristically pragmatist philosophy. Naturally I draw inspiration and/or ideas from philosophers who do not identify as pragmatists (after all, we all reject the Cartesian mirror of nature). But in practice this can lead to some discomfort. If while pushing a pragmatist line I help myself to a Wittgensteinian (or Davidsonian or Nietzschean) insight, the question will naturally arise: what entitles me to enlist these people in my cause? Am I saying Wittgenstein or Davidson was a pragmatist? What should I make of the differences between these very different philosophers? Read more »

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what

—Change. Resilience. Where do we start? I’ve got no idea. What happens after this? Listen! The answer is here!—

—Change. Resilience. Where do we start? I’ve got no idea. What happens after this? Listen! The answer is here!— In 1940, at the height of Hitler’s invasion of Western Europe, Walter Benjamin, from Vichy France wrote, “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight.”

In 1940, at the height of Hitler’s invasion of Western Europe, Walter Benjamin, from Vichy France wrote, “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight.”

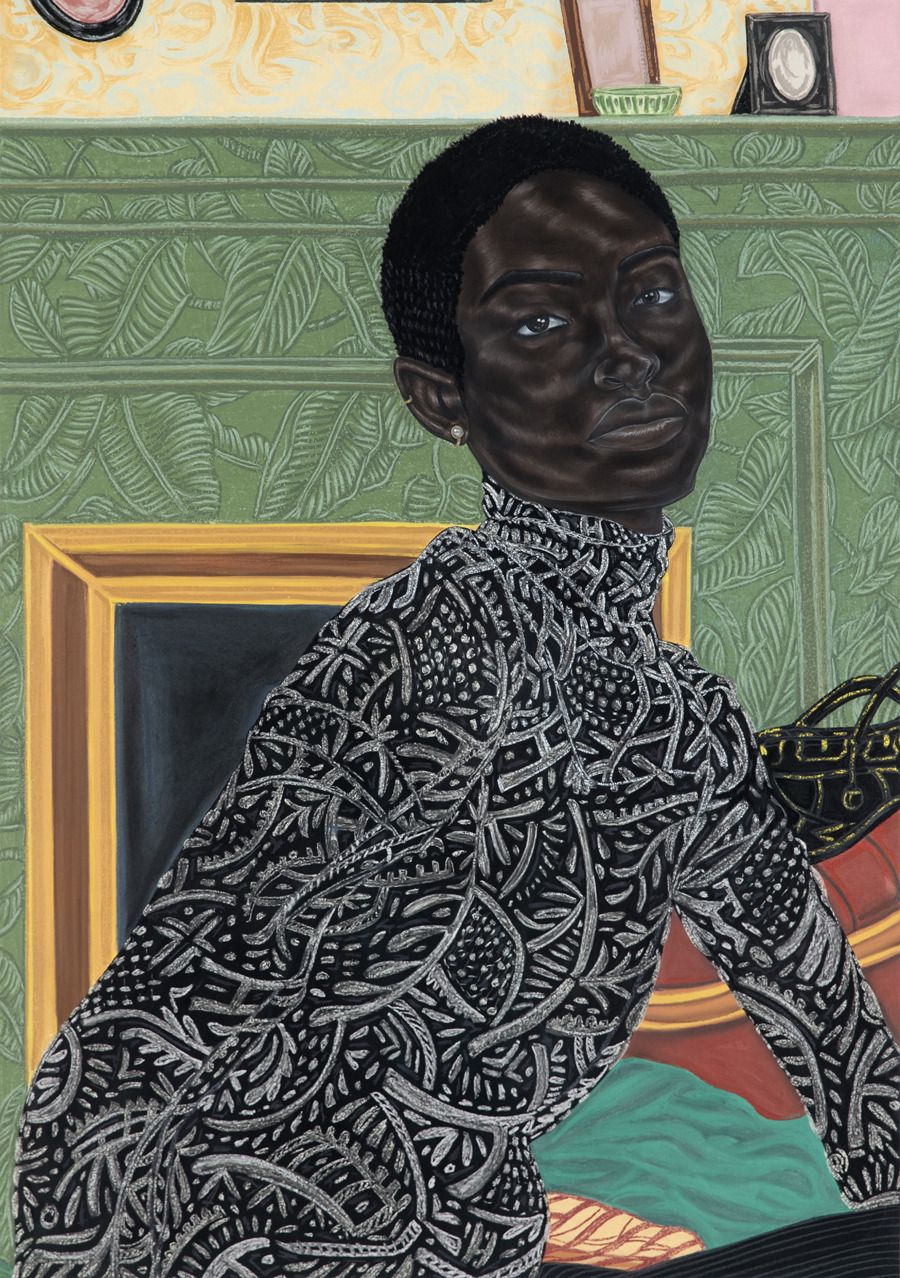

Mourning is in season. Newspapers of record these days publish interactive mass obituaries, images of “ordinary” people fallen to “the opioid crisis” or to Covid-19 (the front page of the Sunday New York Times was recently riven down the middle by a monolith composed of thousands of dots, growing denser towards the base, each representing a victim of the virus: the whole reminiscent of the graphic tributes to 9/11). The inauguration of the US president in January featured, in lieu of most spectators, ranks of flags, symbolizing the past year’s losses. The annual observation of International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Germany, held this year as for the past quarter century on January 27 at the Reichstag in Berlin, featured a remarkable ceremony marrying reconciliation with the starkest grief. In his latest book, the memoir-cum-poetics Inside Story, Martin Amis eschews his characteristic charades in a sincere and extended eulogy for Saul Bellow, Philip Larkin, and Christopher Hitchens, three of the central figures in the author’s professional and affective life. And, 15 years after it first appeared, The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion’s essay on death and bereavement, persists on various bestseller lists.

Mourning is in season. Newspapers of record these days publish interactive mass obituaries, images of “ordinary” people fallen to “the opioid crisis” or to Covid-19 (the front page of the Sunday New York Times was recently riven down the middle by a monolith composed of thousands of dots, growing denser towards the base, each representing a victim of the virus: the whole reminiscent of the graphic tributes to 9/11). The inauguration of the US president in January featured, in lieu of most spectators, ranks of flags, symbolizing the past year’s losses. The annual observation of International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Germany, held this year as for the past quarter century on January 27 at the Reichstag in Berlin, featured a remarkable ceremony marrying reconciliation with the starkest grief. In his latest book, the memoir-cum-poetics Inside Story, Martin Amis eschews his characteristic charades in a sincere and extended eulogy for Saul Bellow, Philip Larkin, and Christopher Hitchens, three of the central figures in the author’s professional and affective life. And, 15 years after it first appeared, The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion’s essay on death and bereavement, persists on various bestseller lists. Unfortunately, it is always worth your time to read a book in praise of the humanities. Given the unenviable position of the humanities in public education and in contemporary cultural and (especially) political discourse about valuable expertise, any author that comes to their defense has to find a strategy to shift the narrative, and will thereby almost invariably do something interesting.

Unfortunately, it is always worth your time to read a book in praise of the humanities. Given the unenviable position of the humanities in public education and in contemporary cultural and (especially) political discourse about valuable expertise, any author that comes to their defense has to find a strategy to shift the narrative, and will thereby almost invariably do something interesting.

Former Finnish President and

Former Finnish President and  I just spent two months living on the Caribbean island of Grenada. It’s a wonderful place with a somewhat antiquated healthcare system. To visit Grenada, I had to have a negative PCR test within 72 hours of flying. I was planning to go to a clinic and wait in line, which I’d done for a previous PCR test. I’d waited in line in the freezing cold for almost 3 hours. But a couple of weeks before my flight in January, Jet Blue let me know that Grenada was accepting PCR tests through a company called Vault who would mail me an at-home test. I signed up, they sent me the test, and three days before my flight, I logged onto a Zoom call with Vault from the comfort of my own living room. My test kit had a barcode and I had to show that to the technician on the Zoom. She then watched me spit into the vial with the barcode and instructed me how to package up the kit appropriately to send it back. I walked it over to UPS 30 minutes later, and within 48 hours, I received my results by email.

I just spent two months living on the Caribbean island of Grenada. It’s a wonderful place with a somewhat antiquated healthcare system. To visit Grenada, I had to have a negative PCR test within 72 hours of flying. I was planning to go to a clinic and wait in line, which I’d done for a previous PCR test. I’d waited in line in the freezing cold for almost 3 hours. But a couple of weeks before my flight in January, Jet Blue let me know that Grenada was accepting PCR tests through a company called Vault who would mail me an at-home test. I signed up, they sent me the test, and three days before my flight, I logged onto a Zoom call with Vault from the comfort of my own living room. My test kit had a barcode and I had to show that to the technician on the Zoom. She then watched me spit into the vial with the barcode and instructed me how to package up the kit appropriately to send it back. I walked it over to UPS 30 minutes later, and within 48 hours, I received my results by email. The Machine has me in its tentacles. Some algorithm thinks I really want to buy classical sheet music, and it is not going to be discouraged. Another (or, perhaps it is the same) insists that now is the time to invest in toner cartridges, running shoes, dress shirts, and incredibly expensive real estate.

The Machine has me in its tentacles. Some algorithm thinks I really want to buy classical sheet music, and it is not going to be discouraged. Another (or, perhaps it is the same) insists that now is the time to invest in toner cartridges, running shoes, dress shirts, and incredibly expensive real estate.

Two profound horrors have plagued the world in recent times: the Covid-19 pandemic and the Trump presidency. And after years of dread, their recent decline has brought me a brief respite of peace.

Two profound horrors have plagued the world in recent times: the Covid-19 pandemic and the Trump presidency. And after years of dread, their recent decline has brought me a brief respite of peace. Whenever I discover a band that sports an accordion in the lineup, I’m ready to listen.

Whenever I discover a band that sports an accordion in the lineup, I’m ready to listen. An empty space sits where I once sat. I miss it. I miss the strangers I shared it with, and a few regulars with whom I achieved a nodding relationship. A couple of baristas I might greet and chat up. Very briefly.

An empty space sits where I once sat. I miss it. I miss the strangers I shared it with, and a few regulars with whom I achieved a nodding relationship. A couple of baristas I might greet and chat up. Very briefly.