by Mike O’Brien

They say that everyone’s a critic. Some more than others. I have a particularly critical streak, that occasionally strays into full-on curmudgeonry. I have a few excuses. First, the generally awful and worsening state of the world tends to put me into a bit of cranky mood. Second, I am lazy, and picking at the flaws in other people’s work is easier than creating something new. And third, there is a lot of really awful, slap-dash work being done in the world of letters that cries out for detraction.

As a break, if not an antidote, to my nay-saying tendencies, I’m going to attempt something a little more constructive this time around. My first column, way back when, was basically a riff on all the facets of my generalized anxiety, and the ecological facet featured prominently there, but there’s still some unpacking left to do.

First, some predictions. After all, anxiety implies that I think something is going to happen, and in this case that something is very bad and very difficult to avoid. Mass extinction will continue, and continue to accelerate, for the rest of my life and beyond. Global warming, ocean acidification, habitat destruction and atmospheric carbonization will continue to blow past every “point of no return” that scientists set, and narrowly human-regarding effects will continue to immiserate billions of people. If we were the kinds of creatures, organized in the kinds of societies, that were capable to avoiding these inevitabilities, we would not be as far along the road to perdition as we are. This is not about what might happen. This is about what has happened and will continue to happen. Read more »

Jesus is reported to have critiqued the seventh commandment as follows:

Jesus is reported to have critiqued the seventh commandment as follows:  by Thomas R. Wells

by Thomas R. Wells

We both have daughters who are good at math, but opted out of advanced math. In so doing, they effectively closed off entry into math-intensive fields of study at university such as physics, engineering, economics, and computer science. They used to be enthusiastic about math, but as early as grade three this enthusiasm waned, and they weren’t alone. It was a pattern we observed repeatedly in their female friends during those early school years, as boys slowly inched ahead.

We both have daughters who are good at math, but opted out of advanced math. In so doing, they effectively closed off entry into math-intensive fields of study at university such as physics, engineering, economics, and computer science. They used to be enthusiastic about math, but as early as grade three this enthusiasm waned, and they weren’t alone. It was a pattern we observed repeatedly in their female friends during those early school years, as boys slowly inched ahead.

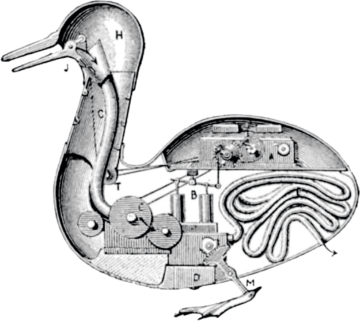

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

The disappointing new film

The disappointing new film  Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us.

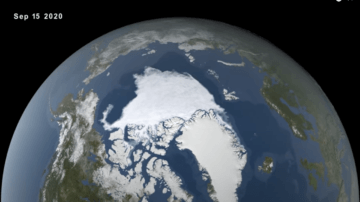

Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us. In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic

In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic