by Jeroen Bouterse

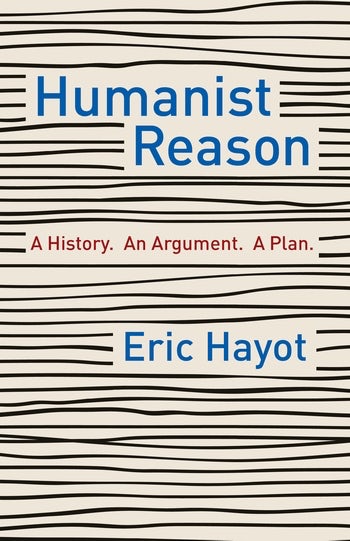

Unfortunately, it is always worth your time to read a book in praise of the humanities. Given the unenviable position of the humanities in public education and in contemporary cultural and (especially) political discourse about valuable expertise, any author that comes to their defense has to find a strategy to shift the narrative, and will thereby almost invariably do something interesting.

Unfortunately, it is always worth your time to read a book in praise of the humanities. Given the unenviable position of the humanities in public education and in contemporary cultural and (especially) political discourse about valuable expertise, any author that comes to their defense has to find a strategy to shift the narrative, and will thereby almost invariably do something interesting.

They move our focus from economic value to democracy and citizenship, for example. Or they argue that there is not actually a mismatch between the skills provided by a well-balanced liberal arts curriculum and the demands of technocapitalism, or that the humanities themselves produce the same kinds of intellectual goods as the natural sciences with which they tend to be contrasted.

These apologies are intellectually creative, though with luck some of them may grow to be new clichés. In their diversity, they also have something in common, which is that they project a rather straightforward view of the knowledge that the humanities and (other) sciences produce. One point on Martha Nussbaum’s agenda in Not For Profit, for instance, is to “teach real and true things about other groups”.

I feel slightly uneasy about this. Maybe this kind of book is not the place to get all difficult about the words “real and true”, but whenever elevator words like those are used with such confidence, part of me is inclined to get difficult about them – to look for the social and cultural interests that put them there, for instance. What is more, the place where I learned to ask those questions was during my history major; they seem to me to point to something that is particular about the humanities, something that gets lost in these defenses. Read more »

Former Finnish President and

Former Finnish President and  I just spent two months living on the Caribbean island of Grenada. It’s a wonderful place with a somewhat antiquated healthcare system. To visit Grenada, I had to have a negative PCR test within 72 hours of flying. I was planning to go to a clinic and wait in line, which I’d done for a previous PCR test. I’d waited in line in the freezing cold for almost 3 hours. But a couple of weeks before my flight in January, Jet Blue let me know that Grenada was accepting PCR tests through a company called Vault who would mail me an at-home test. I signed up, they sent me the test, and three days before my flight, I logged onto a Zoom call with Vault from the comfort of my own living room. My test kit had a barcode and I had to show that to the technician on the Zoom. She then watched me spit into the vial with the barcode and instructed me how to package up the kit appropriately to send it back. I walked it over to UPS 30 minutes later, and within 48 hours, I received my results by email.

I just spent two months living on the Caribbean island of Grenada. It’s a wonderful place with a somewhat antiquated healthcare system. To visit Grenada, I had to have a negative PCR test within 72 hours of flying. I was planning to go to a clinic and wait in line, which I’d done for a previous PCR test. I’d waited in line in the freezing cold for almost 3 hours. But a couple of weeks before my flight in January, Jet Blue let me know that Grenada was accepting PCR tests through a company called Vault who would mail me an at-home test. I signed up, they sent me the test, and three days before my flight, I logged onto a Zoom call with Vault from the comfort of my own living room. My test kit had a barcode and I had to show that to the technician on the Zoom. She then watched me spit into the vial with the barcode and instructed me how to package up the kit appropriately to send it back. I walked it over to UPS 30 minutes later, and within 48 hours, I received my results by email. The Machine has me in its tentacles. Some algorithm thinks I really want to buy classical sheet music, and it is not going to be discouraged. Another (or, perhaps it is the same) insists that now is the time to invest in toner cartridges, running shoes, dress shirts, and incredibly expensive real estate.

The Machine has me in its tentacles. Some algorithm thinks I really want to buy classical sheet music, and it is not going to be discouraged. Another (or, perhaps it is the same) insists that now is the time to invest in toner cartridges, running shoes, dress shirts, and incredibly expensive real estate.

Two profound horrors have plagued the world in recent times: the Covid-19 pandemic and the Trump presidency. And after years of dread, their recent decline has brought me a brief respite of peace.

Two profound horrors have plagued the world in recent times: the Covid-19 pandemic and the Trump presidency. And after years of dread, their recent decline has brought me a brief respite of peace. Whenever I discover a band that sports an accordion in the lineup, I’m ready to listen.

Whenever I discover a band that sports an accordion in the lineup, I’m ready to listen. An empty space sits where I once sat. I miss it. I miss the strangers I shared it with, and a few regulars with whom I achieved a nodding relationship. A couple of baristas I might greet and chat up. Very briefly.

An empty space sits where I once sat. I miss it. I miss the strangers I shared it with, and a few regulars with whom I achieved a nodding relationship. A couple of baristas I might greet and chat up. Very briefly.

There is a story that Clemenceau, the Prime Minister of France, was in conversation with some German representatives during the Paris peace negations in 1919 that led to the Treaty of Versailles. One of the Germans said something to the effect that in a hundred years time historians would wonder what had really been the cause of the Great War and who had been really responsible. Clemenceau, so the story goes, retorted that one thing was certain: ‘the historians will not say that Belgium invaded Germany’.

There is a story that Clemenceau, the Prime Minister of France, was in conversation with some German representatives during the Paris peace negations in 1919 that led to the Treaty of Versailles. One of the Germans said something to the effect that in a hundred years time historians would wonder what had really been the cause of the Great War and who had been really responsible. Clemenceau, so the story goes, retorted that one thing was certain: ‘the historians will not say that Belgium invaded Germany’.

We are not where we were one year ago—or have we just returned?

We are not where we were one year ago—or have we just returned? In the part of my life when I was most actively trying to invent myself as a writer, I was working as a high school teacher and was desperately unhappy. (Notice the way that I put this: “I was working as a high school teacher,” not “I was a high school teacher”; the notion that a job defines a person still disgusts me.) In the evenings, I left work and wrote magazine pitches, not as many, I realize in retrospect, as could have brought me success, but enough to keep me talkative in the teacher’s lounge. I had the impression, back then, that a writer could make a name for himself on the basis of a single strong piece, and since my work was deeply derivative—I was, after all, inexperienced—I hatched a plan.

In the part of my life when I was most actively trying to invent myself as a writer, I was working as a high school teacher and was desperately unhappy. (Notice the way that I put this: “I was working as a high school teacher,” not “I was a high school teacher”; the notion that a job defines a person still disgusts me.) In the evenings, I left work and wrote magazine pitches, not as many, I realize in retrospect, as could have brought me success, but enough to keep me talkative in the teacher’s lounge. I had the impression, back then, that a writer could make a name for himself on the basis of a single strong piece, and since my work was deeply derivative—I was, after all, inexperienced—I hatched a plan.