by Thomas Larson

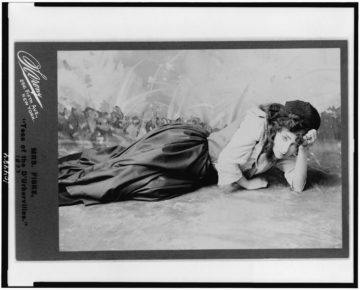

One late spring day in my twelfth-grade English class, my teacher carried a box up and down the aisles, handing each of the thirty students a new Signet Classic paperback. Mr. Demorest, who had a waddle under his chin and a doo-wop singer’s curve in his hairdo, said this novel might be tough reading and pledged plenty of mimeos. He said the school district had prepared us by reading, in previous grades, Silas Marner, Lord of the Flies, A Separate Peace, and The Scarlet Letter, whose baroque language (“Fruits, milk, freshest butter, will make thy fleshy tabernacle youthful”) brought a cascade of snickers from the back of the room. Demorest said that he’d taught this novel before, but he’d be reading it with us again, since with literature there was always more to glean. That word glean fell inside me like a coin tossed in a fountain. The novel was Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles.

Demorest said to get through the first 50 pages until Tess meets Alec. What’s the story? It’s about a girl becoming a woman. As we’ll see, she has a child by one man, Alec, runs from him and marries another, name of Angel. Angel is her true love but, fearful he’ll discover her dark secret on his own, confesses the child’s fate to him. Mortified, Angel abandons her, and she ends up with the first man again, with whom she is forced, for the sake of her family and her reputation (what’s left of it) to—well, you’ll see, he said. Don’t get hung up on the names of English villages. You might look up any Biblical allusions. Pay close attention to how the book makes you feel. Does it make you feel? Where in the story are you moved? Make a mark. Do you care what happens to Tess? Why? Think about it—what does Alec and Angel want from Tess and what does she want from these two men, opposites though they may be?

At home, in bed, I smelled the book’s pages, a ripe odor of pulp and bleach. I took in the familiar pattern of pre-text information (colophon, chapter titles, author bio). The novel’s agreeable mass, its hand-fit feeling when held, was like a hammer whose usefulness was obvious but whose hidden power for damage eluded if not frightened me.

Uneducated, rural, sixteen-year-old Tess Durbeyfield meets effete, landed Alec d’Urberville, a distant cousin, who, we learn eventually, has taken the old Norman name, pretending to the pedigree. He employs Tess so she can earn money for her near-destitute family. As Tess makes her neutrality and shyness evident, Alec is bedazzled by her and her central attribute, “a fulness of growth, which made her appear more of a woman than she really was.” There follows a scene of strawberry-picking and rose-gathering, and then an awkward intimacy, Alec-led. “For a moment . . . he inclined his face toward her as if—but, no: he thought better of it, and let her go.” A page later, Tess is returning home on a coach full of passengers, her body garlanded with flowers by Alec.

[She] became aware of the spectacle she presented to their surprised visions: roses at her breast; roses in her hat; roses and strawberries in her basket to the brim. She blushed, and said confusedly that the flowers had been given to her.

I made a mark in the margin. I was moved by Alec’s desire for this girl, close to my age at the time. What he saw in her, the blush, the vulnerability, I, too, wanted in a partner. But Tess forcefully rejects his advances just as she seems drawn to them. She wants to be wanted and when she is, she feels no reciprocal desire. Which part of her mirrored part of me? The Alec part? The Tess part? Tess’s hesitancy I found oddly magnetic. When she sees herself as Alec sees her, she loses part of herself in him. I thought she couldn’t win. But then fateful events take over. After Alec is riding Tess home from a party, they get lost in a fog-bound wood, perhaps intentionally. Alec has Tess wait for him while he scouts out their whereabouts.

Not long after, he returns, and Alec, Hardy writes, “stooped; and heard a gentle regular breathing. He knelt and bent lower, till her breath warmed his face, and in a moment his cheek was in contact with hers. She was sleeping soundly, and upon her eyelashes there lingered tears.”

In that moment, Alec, we assume, is riven with male instinct. Hardy, hemmed in by Victorian censorship, barely indicates the sexual violation, asking, “Where was Tess’s guardian angel”? He writes of the assault without writing it, her condition plagued by an “unreflecting inevitableness.”

Why it was that upon this beautiful feminine tissue, sensitive as gossamer, and practically blank as snow as yet, there should have been traced such a coarse pattern as it was doomed to receive; why so often the coarse appropriates the finer thus, the wrong man the woman, the wrong woman the man.

The ambiguous fealty Hardy has for her—“sensitive” and “blank”—is the creator’s love, closer to a merciless adoration than anything else. He’s birthed her into a world in which she will briefly treasure her possibility only to have the author turn and destroy her.

Already I was torn. Doom—blossoming into pregnancy—takes Tess; I felt sorry for her because it was not with a man she loved. (The same thing had happened to the brightest girl I knew in high school who, tummy-rounding, was pulled out, Catholic-homed, and never returned.) I had no experience of Tess’s arc into womanhood, her quicksand of poverty. But I could relish the novel’s spiritual theme contending with its sensual one (Hardy’s great gift). Were Hardy’s folk guided by his hand or the hand of God? Was God fate? If all things are pre-determined, as the Calvinists have it, what’s the use of our free will?

The novel preached an alienist’s creed, showcased histrionic helplessness. Tess can’t help but express her feeling to Alec: She dislikes his kissing her, and she tells him what she feels: “I don’t love you.” But Alec doesn’t listen. He doesn’t have to since Tess must rely on him for survival. Such indenture is her fate. Hardy tells us, her “own people” would have said of Tess’s tragedy, “It was to be.”

Into the second week, Demorest said, read until you find out what happens to Tess’s baby, Sorrow. (A character named for an emotion?) What does Tess do? How do you feel about her fate? I read the novel in our living room and pondered his questions—until something came, unbidden, through my glassy stare out the window at a crab apple tree in the yard that was not only a crab apple tree in the yard but a crab apple tree that grew alongside the life cycle of my family, its spindly singularity I had noticed but not noticed hundreds of times before, at Christmas, in radiant Spring, during afternoon bouts of meditative, brother-banished reading—and there it was, still there, still being/becoming its leafy, branchy self, but now also the ongoing summation of my witnessing its being/becoming. Hardy’s mesmerizing prose was no different.

As I read, I felt a huge wave rising, its big-and-bigger curl carrying me. The frisson on my skin was Hardy’s emphatic intent. This tact was the opposite of a poem’s concision (emphasis placed by packing and paring away) or of a song’s repetition (emphasis placed by melodic and rhythmic repetition). Hardy boarded layers of brick and mortar, building walls and archways, floors, rafters, ceilings, stairwells, until the edifice stood before me with an immense intractability. The whole of it apparent like a city passed through and visible in the rearview mirror. Neither poem nor melody could accomplish that.

After Alec violates Tess, after the death of Sorrow, and after Tess moves on to another loathsome job, she centers her survival in social obligation, barns and beds of straw, friendships Tess makes with “milk maidens” like herself (none of whom, Hardy shows us, is as pretty as she). It’s a dull and honest life working on a poultry-farm, a dairy-farm, a turnip-slicing operation, with Tess “chopping off with a bill-hook the fibres and earth from each root.” Hardy, though, emphasizes the rude labor of harvest, its monotony, its wretched wage, its servitude; once the next fateful romantic turn arrives—Angel, the man she loves and marries—Tess finds the forces of her past “indiscretion,” her independence, and her married love contending in her, perhaps, for her.

Now Demorest guided us, the adventuresome, toward deeper waters. Did you know that Tess has several contrasting natures? How can one simple country girl have several? We all do; people are complex. Here—Demorest noted a page number and waited till we flipped there—is her lofty nature. Angel, Hardy writes, “would sometimes catch her large, worshipful eyes, that had no bottom to them, looking at him from their depths, as if she saw something immortal before her.” Here he said is her practical cow-milking side: “Tess, like her compeers, soon discovered which of the cows had a preference for her style of manipulation. . . . She endeavoured conscientiously to take the animals just as they came, excepting the very hard yielders which she could not yet manage.” And here is her doomed self, analyzing an imaginary conversation with Angel on their wedding night. “‘Why do I love you so!’” she hears him say. “[S]he whispered there alone; ‘for she you love is not my real self, but one in my image; the one I might have been!’”

For next week, Demorest said, read up to her marriage to Angel Clare and what happens on their wedding night—but I had already read on and on, to and beyond the wedding, to the mystic-laden end (set at Stonehenge!), not seeing all the seams and symbols of what I had read (especially Hardy’s quarrel with Christianity), but relying on Demorest who’d broach the most salient questions for us. The story engulfed me. No, place the emphasis right: I was engulfed by the story. As though this, paying attention to the fact and fancy of my aliveness while I was reading was the point.

One day Demorest asked us, Why do you think Hardy says that Tess “was in love with her own ruin”? He cranked open a few windows—this, a humid St. Louis May day. Here was a prickly query. Remember, he said, Hardy is speaking to us indirectly, through the characters and their actions in the novel. A pastor, a philosopher, talks about the meaning of life directly. But a novelist, a writer, dissects things with the language of literature. What is that language? He let that word hang in the air for us to glean.

Demorest said, “By way of answering, let me pose one idea.” He went to the board and wrote CHARACTER.

“When Hardy says that Tess is in love with her own ruin,” Demorest continued, “that’s her character. She can’t just be pushed into bad things or merely be acted upon. That’s melodrama. She has a say. That’s character. You have free will. You make choices. Such as when to divulge your secrets. When to run. When to stay and speak up for yourself. Yes, there’s a big ugly world out there that will ruin you. But you fight back. It’s the fighting back in people we admire. That’s their character, especially in life and death situations.”

“I don’t see her making a lot of her own choices,” I said, blurting it out from my desk. I wanted a one-on-one conversation with Demorest because my questions were itching me like a poison ivy rash.

“Well, you’re right,” he said, smiling at such an engaged participant. “The men—her father, Alec, Angel—they all want her to be how they see her. Innocent, beautiful. True. But think again. Though she wants to marry Angel for love, she can’t tell him the truth about Alec and the baby. That’s her character. For whatever reason. She can’t say what she wants. She even says, ‘I wish I were never born.’ It’s not her fault. Her independence has been stolen from her.”

I disagreed. “I think Tess fights back all the time,” I said. “She leaves and finds her way in the world despite of what happens to her, whether one lousy guy caused it or she caused it. And when she kills Alec, boy, that’s a sign of character. To be free of him, she kills him. Good for her. That’s character.”

My classmates laughed, I recall at the time, mostly because I was going toe-to-toe with Demorest, not out of spite or one-upping him but just because my voice was suddenly as present as his. I seemed to wake them up from their slumber, as if the novel we read (if they even read it), was merely acting on them and didn’t require their going through it.

For a moment, Demorest gazed into the space above our heads; he resembled a man standing beside the grave of his mother. “Your points are well taken. So if I follow your logic, it’s possible that Tess’s acts to bring about the things she doesn’t want. And yes, that takes character. I think that’s one thing we might agree on.” I was befuddled by this. I still am.

Demorest went on, though he seemed to take a new direction, unplanned. I couldn’t tell whether I had interrupted his flow of thought from what he was going to cover or if he was improvising, destabilized by my dissent, and began pacing the room and palming the book like a preacher. He walked, then stopped to deliver insights and queries as they came to him. He said that questions from readers (like me, I assumed) led writers to explore new ideas in their books. He said authors were part of a dialogue with their own novels; they changed because what they wrote changed them. He admitting to loving those writers, like Hardy and other English novelists, who pushed their free and doomed folk into one another’s messy lives until their exploited innocence and unwise choices or churlish fate disrupted their own lazy opinions and prejudices—and off-kilter they remained, neither saved nor redeemed. He said such literary men could build empires with their work, like Dickens or George Eliot (a woman I soon discovered), which, after they exhausted their characters, they deepened their desire to explore and conquer more empire of the human animal, not less.

By the time he got to “human animal,” he’d lost most of the class. He had, as my father would have said, climbed aboard and starting riding “his high horse.” But I loved it, loved his enthusiasm for serious make-believe, loved the fact that a teacher who could testify to what moved him could move us and not that dry droning on and on about the French and Indian war or the sides of an Isosceles triangle.

I couldn’t say this when I was in high school, but Tess was my conversion, Demorest its messenger, Hardy, its prophet. Hardy: He of the pinched face, surly air, a paranoid who (I’d learn much later, reading the biographies) ghostwrote his own biography, a literary mix of P. T. Barnum and Babe Ruth, a switch-hitter who excelled as humanly at novel-writing as he did musically at poetry-making like a few others who followed him—D.H. Lawrence is one, Robert Penn Warren another. Into my life from Hardy and a critical sensibility from Demorest came a gale of consciousness blowing through me, a sensory expansion, the Siren of literature holding me fast. Tess’s story enchanted me in a way that the novel and hundreds like it, though never as luxurious and woebegone as this tragedy, have ever since.