by Brooks Riley

We are not where we were one year ago—or have we just returned?

We are not where we were one year ago—or have we just returned?

This is the paradox of the pandemic: Lockdown has sent many of us on the wildest of journeys—not to a different place, but to a different self, even if such a destination is temporary.

What if a consequence of going nowhere and doing nothing for a year is finding out there’s a stranger living inside you? Unlike yourself these days, the stranger isn’t in isolation. It goes everywhere you can’t, especially down rabbit holes where the ‘you’ you think you know would never go. Uninvited, this stranger is no guest, it’s just been squatting in your brain until the time was right.

Don’t confuse the stranger with an inner voice. The stranger doesn’t chat or chatter. It’s not interested in your opinions, nor does it want to convince you of something, or help you ‘harness’ an inner anything. Its agenda is to hold you hostage, no questions taken, no answers given.

I’m unclear as to the stranger’s gender. Is it a girl, a middle-aged man, a woman, an old lady, a boy? Does it matter now that the stranger lives in the part of yourself that once indulged in its own peregrinations?

When you weren’t looking, it pulled up a chair next to you and grabbed the mouse, that most direct instrument of intent, and began to map out a new itinerary. It’s become harder not to notice as it steers your ship of self away from its charted course and into unknown territory. An interloper in your command central, the stranger now begins to assert itself, to exert its will in appalling ways–mostly having to do with music.

Take Schubert. I’ve walked arm in arm with Schubert all my life, his music a familiar refuge when pathos skirts the edges of my consciousness looking for comfort. Like many of my dead idols, I think of him as mine, plagued by the feeling I could I have saved him from his fate, enabled a few more years of masterpieces, eased his loneliness, made him smile. When I listen to Schubert, I am often in his head, not mine, incorporating the woes and inequities of poverty, rejection, illness. These are the times when I hate Goethe for dismissing the teenage composer’s lieder versions of his poetic works Erlkönig and the Gretchen am Spinnrade from Faust. To be fair, Schubert wasn’t the only one setting Goethe’s words to music and sending these efforts to Weimar for approval or recognition. But I wish he had lived long enough to have the last laugh, when the two works became more famous than the originals that inspired them. Maybe it would have been enough if Goethe had lived that long.

So it wasn’t surprising that at the beginning of the pandemic, Schubert showed up on my playlist, with an appropriately mournful Litanei (D343) for those who, wouldn’t survive it. It was meant to be consoling, but as I’ve written before, music can only go so far.

As I moved on to Schubert’s Nacht und Träume, a personal favorite in the version sung by baritone Matthias Goerne, a strange aversion to it began to spread like a stain through my listening pleasure. The lied felt hollow now, and somehow ineffectual, through no fault of the performers. How could this deep mahogany paean to night and dreams become so irrelevant, especially to a seasoned dreamer like myself? I wanted to rip out the lyrics and rebuild the song from scratch—not with another melody sung to deceive with loveliness, but with uttered words—angry ones that would bound over the complex topography of the human speaking voice. I wanted to rap.

I first heard rap music in the Eighties coming from boomboxes on the street in my Upper West Side New York neighborhood. I loved the profanity, the funk, the flaunting of rhymes, the spit of consonants, and above all the abandonment of tune. ‘This won’t last,’ I thought, even as I admired some of it, including MC Solaar, a French rapper.

Now I wanted to rap, but why? Rap is about flow, about flexing, about swag, all words that have enriched my vocabulary since I began my magical mystery detour, but not words that anyone would connect to my person. I’ve learned these words because the stranger got me to listen to rap, from Eminem to Megan Thee Stallion, to DaBaby to the rap line of BTS, and especially to Agust D, the alter ego of Suga. From there it was a short step to some edifying moments on YouTube: Reaction videos of Americans listening to Korean rap brought me closer to my country than I’ve been in decades. They taught me rap lingo. Their joy at the incomprehensible flows in a foreign language was a refreshing foil against the ongoing crises out there in the world.

Korean is an inflection-rich language that lends itself well to rap. It sweeps up and down the scales of the speaking voice with surprising dramatic emphases and unexpected punctuations. Rapid Korean is a flow unto itself, full of triplets and accentuations spit faster than any rapper in English. For me, it was the ferocious musicality of those syllables that moved me, removed from their meaning, along with the flow changes, complicated rhythmic structures and verbal percussion.

With classical music effectively destroyed for the time being (Schubert wasn’t the only casualty; Wagner, Schumann and Mahler took hits, so did Mozart), I relaxed into my new-fangled self, letting the stranger drag me away from my comfort zone into a maelstrom of syllables flung far and wide, and decibels long ignored. I even began to like pop music.

But still I wondered, ‘Where is this going?’ As I stole sidelong glances at the stranger, an individual slowly emerged. He’s a male, of medium build, and looks to be in his late twenties. I can’t see his face. I don’t want to see it. TMI. Where did this young man come from? Is he pushing a new genre of rap culled from the ashes of classical music, (say, a rap version of An die Musik called An den Wahnsinn) or is he just promoting an aggressive mindset in whatever musical category?

My old self was in danger of disappearing, replaced by the questionable Weltanschauung of a twenty-something. It’s clear that the pandemic had unleashed a kind of psychosis. I was feeling generic rage, unrelated to any temporary impositions on my lifestyle (of which there were none great enough to induce the rending of garments). I was railing (and rapping in my mind) at the collective fate of millions of lives—so dire, so undeserved, so unfair. This helpless sense of doom required brutalism, not lyricism, found at last in the machine-gun tempos of Agust D’s rap flows in the eponymous Agust D (2016) and recent Daechwita, a blast of dissonant bile directed at pill-popping wannabes but more importantly at his older rapper self, the tyrant king.

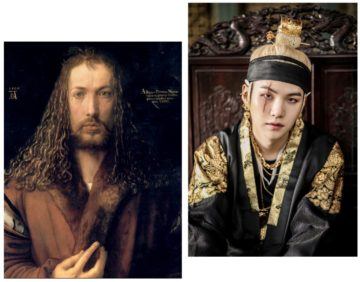

It was my subconscious that made the connection between another idol Albrecht Dürer and Agust D early one morning, at the end of a dream. Thanks to an interactive analysis of Dürer’s Self-portrait from 1500 in the New York Times last summer, I had been able to visit my former neighbor every morning when I opened the browser. A reassuring part of my past was spared the stranger’s hack.

Awake, I realized that there was more to this pairing: Both were 28 years old when they completed their self-portraits. Dürer’s was an affront to the full-frontal depictions of Christ of that time but intended only to personify his talent, not to deify himself. The self-portrait never left his atelier during his lifetime.

Still, there is no doubt that Dürer was flexing in that work, showing off his skills, flaunting the feel of fur between the fingers, making sure you could see the windows reflected in his eyes. The painting was lit, sick, dope, on point, his fits beyond belief. How much more resonant these words now sounded than the stately adjectives ‘infuriating’, ‘arrogant’ art historians have used about this work.

Agust D’s post-Freudian music video of Daechwita is the modern, analytical, cinematic equivalent of a self-portrait, even as it coopts ancient Joseon military music. Agust D is flexing too, while his antagonist/alter ego claims no need to flex (the ultimate flex). There’s plenty of swag in both works, at 3:19 of the music video, and implicit in that ‘You talkin’ to me?’ eye-level gaze of Dürer.

They could both lay claim to AD as initials, (Agust D is D(aegu) T(own) Suga spelled backwards). Both have suffered from the delusions of fan fiction, most recently Dürer as bisexual. Both have perpetuated their works through mass-production, Dürer via a thriving woodcut business, Agust D via streaming on a grand scale. (If you think Daechwita is obscure, check out the number of times it’s been viewed on YouTube since its debut eight months ago.)

Daring to link two such disparate artists may have been a way for me to begin to reassert my old self: Dürer belonged to the old me, while Agust D had shown up with the stranger.

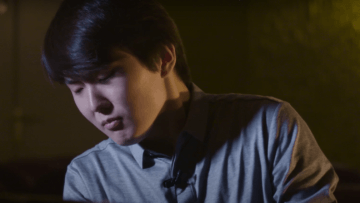

But that didn’t solve the chasm left by my loss of interest in classical music—as disturbing as Covid-related loss of taste must be. I was beginning to despair when an item caught my eye. In January a newly discovered piano sonata by the teenage Mozart would be played for the first time live on YouTube by yet another 28-year-old, Seong-Jin Cho, winner of the Chopin Competition in 2015. Could this be a way back into the musical side of my old self? Was he the stranger?

I wasn’t expecting much—Schubert was more interesting than Mozart at age 17—but something Cho said about ‘story-telling’ in Mozart’s works awakened an old memory of playing the piano as a child. Back then, every simple piece I played had a story to tell, a story without words as suspenseful as any work of fiction, full of intrigue and emotion, which made arriving at the last note a kind of catharsis. When Cho plays Mozart, a viewer can almost hear the story unfold within him. And when he speaks of the Chopin Ballades, loaded words are used, like violence, charm, scary, tragic, or suspenseful phrases like a door opens. . .

There’s a primal narrative force at work in music that doesn’t rely on words to be felt and understood. The more I explored Cho’s broad repertoire, the more I could hear those stories and find their meaning. I was being slowly drawn back to classical music, newly curious about Debussy and Chopin, whom I abandoned decades earlier. But it was finally Schubert, in the end, who brought me home again from my wild journey, with the Wanderer Fantasy in C Major played by Cho in a church in Switzerland last summer to a small audience of socially distanced listeners. And, as if he knows I’ll also someday return to Schubert’s lieder as sung by Matthias Goerne, Cho posted an entire recital on YouTube yesterday, to welcome this wanderer home.

***

Suggested links:

The making of Daechwita (turn on subtitles)

Traditional Daechwita music

Interview with Agust D (turn on subtitles)