by Joan Harvey

For several years I enjoyed discussions about neuroscience with a friend (now deceased) who was a top rock climber. He and his buddies, when not performing solo climbs with torn shoulder muscles and sleeping on cliffside bivouacs, would listen to Sam Harris and talk neuroscience. We have conquered mountains, was their creed; now we will take on the mind. Because of this, and despite the fact that many top neuroscientists are women, and that many neuroscientists come across as gentle and balanced individuals, I got the idea of neuroscience as a slightly competitive macho sport. I grew up among mountains and as a young person I was fond of the Hopkins lines:

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed…

Men and women are now fathoming these mind cliffs and, here and there, claiming first ascents.

In the middle of his new book The Hidden Spring, Mark Solms quotes Einstein: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.” This could describe the thinking behind The Hidden Spring: to make the complex theory within as simple as possible, without dumbing it down so much as to be meaningless. It’s an extraordinarily ambitious undertaking—on the one hand Solms is addressing the “hard problem” of consciousness with his own relatively controversial theory; on the other hand he’s trying to explain general concepts of science (falsifiability, Bayesian theory, the free energy principle, Markov blankets, etc.) to a reader who might not know them, so as to guide them through his thinking.

Solms is successful, to my mind, but there remains the question: Who is the general reader (I salute you, General Reader) to whom he says the book is addressed, and whom he advises to ignore the endnotes aimed at academics? I suppose I qualify as a General Reader, as I have neither a math nor a science background, though I did compulsively read all the endnotes. One needn’t be familiar with the arguments of Nagel and Chalmers or Andy Clark’s predictive processing, as Solms summarizes their arguments clearly; on the other hand it probably doesn’t hurt to have some background, and I suspect the “general” reader who comes to this book will do better with at least an acquaintance with these things. Read more »

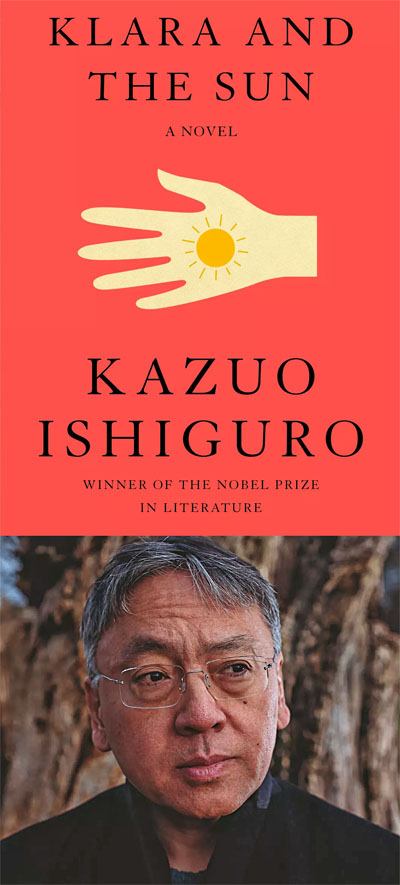

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a  have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the

have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.