by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

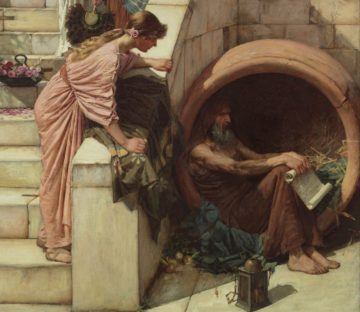

Philosophical Cynicism is widely hailed as a critical voice from the margins. There are good grounds for this assessment. The Cynic confronts dominant culture and exposes its illusions. Diogenes famously walked the streets with a lit lantern, looking for an anthropos (a true human), thereby implying that those around him are not proper humans. He and his father were exiled from Sinope for adulterating the coinage, but his take on the story was that his job was, under direction from the Delphic Oracle, to alter the political norms. And so, as an exile, Diogenes harshly criticized whatever community he found himself in. Whatever their dominant norms were, he was against them.

But Diogenes nevertheless recapitulates many of the norms of his culture, especially in his attitudes regarding people the margin. Women, the gender non-conforming, people with darker skin, and sex workers and their children are treated with casual scorn and are used as foils for displaying Cynic virtue. Certainly, Diogenes’s resistance to the dominant culture is central to the Cynic perspective, but the question is whether his mistreatment of others who are marginalized is also essential. Must Cynicism be misogynist, racist, homophobic, or otherwise exclusionary?

This occasions a general puzzle for social critics. In order to have an edge, social critique must be identifiable as criticism by those to whom it is addressed. This means that criticism must be legible to those criticized. Otherwise, it is simply noise. This condition constrains the radicality of social critique. The more sweeping the criticism of one element of the dominant culture, the more the critic one must hew to its other elements.

To formulate this puzzle, recall the basic stance of the Cynic. The point of cynicism is to invert the critical eye, to make it that it is the outsider who gets to judge the insider. Consider Diogenes’s famous exchange with Alexander the Great. Upon his arrival in Corinth, Alexander comes upon Diogenes relaxing in a sunlit grove. Alexander asks Diogenes if he had need of anything, and Diogenes replied, “Yes, you can stand out of my light.” Diogenes not only spurns the goods that Alexander could give him, but he does not scrape and flatter when in the presence of the great conqueror. Read more »

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily. Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

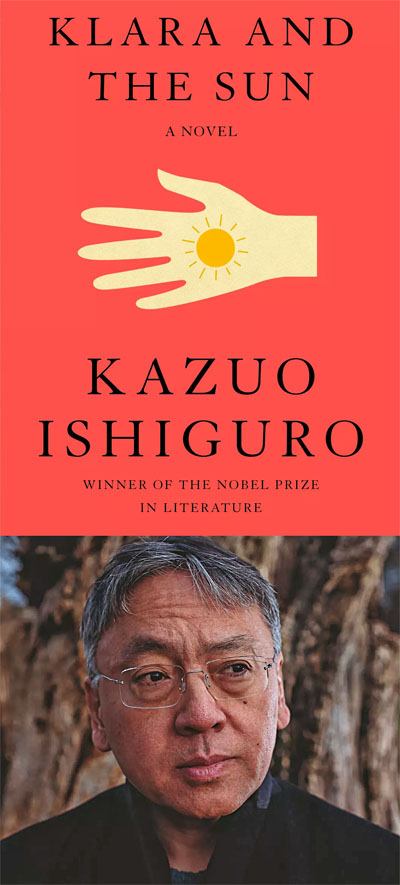

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a  have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the

have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the