by David Oates

A missing tradition is haunting us, though we may not even realize it’s missing. It was called “conservatism,” and in the Anglo-American political tradition it has a record of partnering with liberals to create some of our greatest moments of democratic progress.

Our new president did once publicly hope to govern under a new and restored regime of that legendary chimera “bipartisanship,” liberals and conservatives hammering out compromise bills that advance the public interest. But that fantasy has quickly faded. Even after the departure of the former president and his hateful ways, what’s left of the Republican party seems to be a beast of unqualified partisanship, angry, ravenous, utterly uncompromising.

This became obvious when the “Covid Relief Bill” had to be passed in the Senate with only Democratic votes. Yet it was almost self-evidently needed as a response to an unprecedented public crisis. It was beneficial enough for some Republicans to take credit for it in public . . . despite having voted against it.

Where is the GOP that is heir to, for instance, the conservatives who helped pass civil rights legislation and who founded the Environmental Protection Agency? Or heir to the British conservatives (Tories) who expanded the electorate and made the entire system broader, less class-based, more democratic? Plaintively we ask, where are the conservatives of old? Ay, where are they?

Replaced by reactionaries, every one. And this is not name-calling. It’s sober truth. The United States, as of this writing, has no conservative party. Probably hasn’t for a decade or more.

The grand Anglo-American tradition of careful conservatives offering measured reform and real progress has vanished from America. An apocalyptic trio has replaced them: resentment, revanchism, and reaction. With three “R’s,” alliterative, as if for a tidy little sermon. And I can’t help wondering: what is the sickness of soul that leads to such angry irrationality?

* * *

Once upon a time in the United Kingdom, a Tory government soon to be headed by Benjamin Disraeli oversaw the a huge expansion of the right to vote, doubling the electorate in England and Wales. Some of the issues it addressed will sound familiar to an American audience.

“The Second Reform Act 1867 increased the number of men who could vote in elections. It expanded upon the First Reform Act, passed in 1832 by extending the vote to all householders and lodgers in boroughs who paid rent of £10 a year or more. It also lowered the property threshold which enabled agricultural landowners and tenants with very small amounts of land to vote. This legislation was influenced by the campaign of the Chartist movement, who were dissatisfied by the limited enfranchisement granted in the 1832 Act. The movement, driven by the working classes, petitioned for universal male suffrage and protested when their demands were rejected by Parliament. Eventually, Members of Parliament acknowledged that further reform was necessary.”

The established and titled interests somehow were brought to cede political power, allowing historic Tory districts which had little remaining population – the famous “rotten boroughs” – to have their representation in Parliament halved or combined or dropped altogether. Meanwhile, new seats were added for newly urbanizing populations.

It is remembered as a signal victory of democratic governance. In my graduate studies in nineteenth-century British literature and history, I remember being struck by its strange glow of what might, paradoxically, be called progressive conservatism.

The story of Disraeli himself is fascinating – actually rather lurid. Son of a prosperous English Jew who, after a falling out with the local synagogue, had his family baptized as Christian, Benjamin was just thirteen at the time and in the process of being educated at private schools where he surely felt the sting of the outsider – baptized or not. He was brilliant, florid, dandified. Wrote popular novels, lost money in a financial bubble, had a scandalous affair with the wife of a prominent man. Entered politics, became – despite all of it – Prime Minister. It amazes me, his success. His self-exoticizing. His ability to walk through doors that weren’t ordinarily open to men like him. And finally to lead the Tories into an experiment in broadening democracy. I still can’t quite wrap my mind around him.

* * *

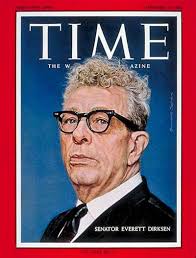

Meanwhile, in America, we could point to a similar moment in the more recent past, when the Senate passed the 1965 Voting Rights Act with overwhelming majorities of both parties. Only two Republicans voted against it. It was the answer to a hundred years of government-sponsored violence and suppression in the South (and slightly more subtle forms of suppression in the North). This act was the muscular follow-on to the celebrated Civil Rights Act of 1964, which had passed the Senate in similar way, with the help of Senate Republican Leader Everett Dirksen and the votes of most Republicans. To read his story is to be reminded that there used to be Republicans who were an important force in the movement toward racial fairness.

Why, one might ask, are our contemporary Republican politicians unable to achieve the level of enlightened conservative progressivism achieved by Victorians (!) of a hundred and fifty years ago? Or our own conservatives of fifty years ago?

For at present Republicans in various American states are forcibly moving in the opposite direction, rolling out what NBC News calls an “avalanche” of bills to restrict voting – two dozen in Texas alone, and perhaps as many as 250 bills proposed nationwide in 43 states by the Washington Post’s count. These bills are obviously reactions to the voting losses of the recent election, in which unprecedented voter turnout produced Democratic victories in the Senate and White House (though Republicans still did well in the House).

* * *

Meanwhile, Democrats in Congress are preparing to push through the “For the People Act.” Its voting protections ought to be rather thrilling to any small-d democratically inclined citizen. The “For the People Act” would:

“remove existing barriers to voting, secure the elections processes to secure the integrity of the vote, expand public financing to fight the pernicious entrenched and moneyed interests, and ban congressional gerrymandering to ensure equal and fair representation in the House of Representatives.”

It would create automatic voter-registration via government databases, and guarantee same-day voter registration as well as regulating early voting days and polling place hours. It would prevent states from purging voters unjustly. And most breathtaking (to a weary American, at least):

“In an attempt to get rid of gerrymandering, the law would require each state to use independent commissions (not made up of lawmakers) to approve newly drawn congressional districts.”

Struggles over voting rights offer good test-cases for democracy (or the absence thereof). There are many ways to make it hard to vote, ways to stack the deck against voters who, for example, are darker of skin, or are recent of arrival, or live in poorer neighborhoods. Recent GOP acts in the state of Georgia offer a case in point. Having lost the popular vote in the two recent special Senate races as well as the Presidential contest, the Republican-dominated state government has enacted a series of measures stamping out the unwelcome specter of poor and black people who tend to vote Democratic. Perhaps most naked was a provision to disallow organized Sunday voting, clearly a backlash against Black churches which traditionally had organized “souls to the polls” caravans to turn out the vote.

And as I attempt to draw this essay into a coherent draft, newly elected Georgia senator Raphael Warnock offers this apt summary:

“We are witnessing right now a massive and unabashed assault on voting rights unlike anything we have seen since the Jim Crow era,” Warnock said, pointing to a wave of bills that limit voting in Republican-controlled states like Arizona and his own Georgia. “This is Jim Crow in new clothes.”

The comparison to bad old days of the segregated South is not political hyperbole. It is important to recall: The heart of the Jim Crow system was preventing Black people from voting. Full stop.

This is not conservatism. This is trying to take back territory lost but never ceded – what old-world politics called revanchism: trying to turn the clock back.

This is not conservatism. This is resentment, or (another old-world term) “ressentiment”: “repressed feelings of envy and hatred which cannot be satisfied.” Think of that unleashed hatred in the January 6 insurrection – that fervor of scorn expressed daily for decades on the Rush Limbaugh radio show, and finally given full voice at Trump rallies. Some of us have been marveling at its stridency. It echoes the anti-Obama Tea Party emotions: unhinged and screaming.

This is not conservative. This is reactionary.

* * *

Reactionary politics can be seen as a kind of fundamentalism. Like fundamentalism in religion, it originates as a desperate push-back against change and especially against modernism. In both the political and the religious realms, fundamentalism is typically dead-set against science and learning. Evidence-based thinking is absent. In its place is an emotional attachment to a fantasy version of the past. It cannot be reasoned with because it is not based in reason but in fear and fantasy.

Sociologically, fundamentalism seems to arise when people feel their social status threatened.

According to Grant Wacker of the Duke University Divinity School (speaking of the origins of modern protestant fundamentalism):

“Social changes of the early twentieth century also fed the flames of protest. Drawn primarily from ranks of “old stock whites,” Fundamentalists felt displaced by the waves of non-Protestant immigrants from southern and eastern Europe flooding America’s cities. They believed they had been betrayed by American statesmen who led the nation into an irresolved war with Germany, the cradle of destructive biblical criticism. They deplored the teaching of evolution in public schools, which they paid for with their taxes, and resented the elitism of professional educators who seemed often to scorn the values of traditional Christian families.”

I have experienced both kinds of fundamentalism first hand, raised in a Baptist household and coming of age as Barry Goldwater ushered in the modern era of reactionary Republicanism. I think I still own my Goldwater button, somewhere in a box of mementos! But as the secretly gay kid in the Baptist pew, I held myself carefully closed and defended, always observing. Our church offered a suburban middle-class sort of evangelicalism, not outwardly strident or mean but leaning toward fundamentalism if you scratched the surface. It liked slogans and absolutes. It did not invite dark-skinned people. It did not believe, really, in history. We had a self-appointed Bible teacher who taught us all sorts of easy outs from the hard work of loving the other humans or struggling with any moral imperatives larger than questions of drinking or necking. The Civil Rights movement? Oh, no worries. Noah’s son Ham was cursed, and that’s why Black people struggle. Divinely ordained. Not our problem.

As I grew older and came to understand the narrowness of such closed systems, it became clear to me that a key feature was black and white thinking. Always that sense of either-or: either you were all-in on our side, or you were the enemy, damned and wrong. And difficult questions weren’t really difficult. They had easy answers that could be memorized.

Developmental psychology tells us that this kind of Manichean thought process is entirely normal – for middle teens. I had a good time adoring Barry for a year or two. Only later was I able to see the obvious: Goldwater gained the nomination as a backlash against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which he vociferously opposed. His candidacy startled party professionals. This was the birth of modern reactionary Republicanism, harnessing popular anger and thinly-disguised racism which Eisenhower Republicans had failed to utilize.

Black-and-white thinking – all or nothing. Not a single GOP vote for the Covid Relief Act. Not a single Republican vote for Obamacare. Not a single hearing for an Obama-nominated Supreme Court candidate. And now the reactionary response to the pandemic is simply to deny its existence. As the reactionary response to losing an election is to deny that the loss even happened. And then to try to roll the clock back to 1955 or so, when an imagined tranquility (and a relative absence of black- and brown-skinned voters) can be fetishized.

It is a sad reality that many people fail to mature into adulthood, staying mired in simplistic thinking and fervent fundamentalisms which give some kind of fortress safety, but which can be catastrophically incompetent in responding to the actual world. Or in making common cause with fellow humans.

This is not to say there are no conservatives left amongst current Republicans. Of course they’re still there – tolerated. Mostly. But those conservatives who have persisted have mostly fallen in step with the all-or-nothing absolutists who now own their party. Mitt Romney is the rare exception, a portraits-in-courage Republican who voted against the party line in the second impeachment case of the former president. Indeed, Romney exemplifies that vanished order of progressive conservatives. As governor of Massachusetts in 2006, he introduced a universal healthcare plan that was passed with bipartisan support. It was a remarkable achievement, progressive and collaborative. It formed the basis for President Obama’s later Affordable Care Act.

Governor Romney’s portrait became somewhat smudged, however, in running for president against Barack Obama. The party required him to denounce Obamacare as if it had had nothing to do with him. And he complied, gamely. Republicans had already moved too far in the reactionary direction to be really interested in the health of millions of fellow citizens.

* * *

A slogan from the early-twentieth century Progressive movement declared that “The cure for the ills of democracy is more democracy.” But what is the cure for the ills of the soul? The anger and fear that drive a person to crave enemies, crave the safety of a band of like people, crave a fortress of warriors and slogans?

When William James published his famous book Varieties of Religious Experience in 1902, the fundamentalist movement in the US and Europe was still young enough to remain unnoticed. The word “fundamentalism” is, I believe, not mentioned in the book. In its place, however, is a long section dealing with both “saintliness” and “fanaticism.” There James reckons with the excess of piety on display with some believers, and asks (rather drolly), “Is it necessary. . .to be quite so fantastically good as that?” He then observes,

“The fruits of religion, in other words, are, like all human products, liable to corruption by excess. Common sense must judge them.”

What is common to all men and women – good sense, the universal experiences of life, the shared human stories of love, loss, pain, and aspiration: that common human heritage is what we must come back to, in the presence of the divisive spirit of reaction. The political fundamentalist (like the religious one) is primarily against things, or rather: against certain people and kinds of people. Always animated by opposition and setting oneself apart from, and above, the hated enemy. (Remember the centrality of “owning the libs” to the legions of Limbaugh listeners – as to the Trump followers.)

Perhaps we could ask: Is it necessary to be quite so fantastically right as that?

Common sense must judge them.

Democracy is little more than a method of sharing governance and universal participation. It is not a policy outcome – liberal or conservative or what have you. It is, like science, simply a method. It aims to count everyone equally, and to set up systems of counting noses that at least approximate fairness to all. In this extreme simplicity, it is, as I like to say, the political expression of the golden rule: as unto one, so unto all.

The singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen was asked by a reporter what he thought of American democracy. Cohen replied: “I think it would be a good idea.” “Democracy” is an aspiration of universal fairness, so it is understood to be never fully achieved. It is always a work in progress, a direction, a daily or yearly struggle. Hence, this attempt at aphorism:

The expansion of democracy is the legitimacy of democracy.

If the circle of participation and fairness is not expanding. . . then the democracy is not healthy. It’s rotting. Democracy legitimizes itself not by perfection, but by its broadening movement towards the goal. Towards that “more perfect” version of itself, as the Framers expressed it. And if – as our current GOP is attempting – the circle of participation is actually contracting, then the democracy is, finally, rotten.

The long road of American history (like the much longer one of British history) remembers each of the expanding milestones. The Jacksonian moment. The abolition of slavery. The franchise extended further and then further still, until every male, and then finally every female, is at least theoretically enfranchised. The ongoing struggle against persistent retrograde systems – Northern racism, Southern racism, lingering sexism. . .

Common sense must judge them all. Our common sense – our shared reality. Not one fantasy pitched against another, nor a mob of fanatics throwing themselves against reality. The common sense.

I can’t pretend to have the answers. But it’s what I think about, when I feel angry and fearful myself. Or when I feel, briefly, hopeful.