by Thomas Larson

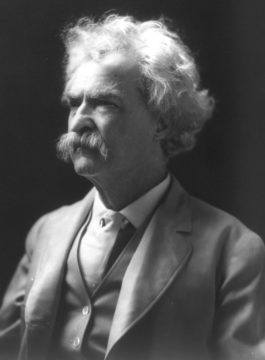

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, among the greatest and most widely read authors in history, is known everywhere by his pen name, Mark Twain. This was the nom de plume Clemens adopted in 1863 as a frontier columnist for The Virginian, a Nevada newspaper. There, he wrote satires and caricatures, bald hoaxes (fake news) and ironic stories of the wild pioneers he met and whose tales he embellished even further. His writerly persona came alive when he began lecturing and yarn spinning from a podium. Over time, his lowkey delivery, his deft timing, coupled with the wizened bumptiousness of a country orator in a white linen suit, captivated audiences in America and Europe, and on world tours. No one has embodied America, in its feral enthusiasms and its institutional hypocrisies, better than Clemens. Dying at 74 in 1910, he played Twain—rather, he became him—for 47 years.

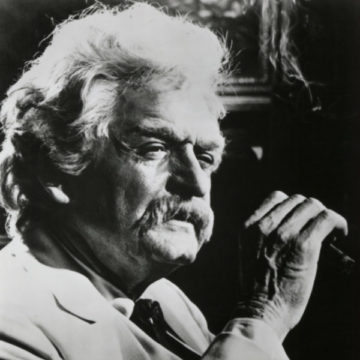

In the early 1950s, a young actor from Cleveland, Ohio, Hal Holbrook, adopted the Twain persona for a stage act, aping the man’s appearance and cornpone speech and dipping into the goldmine of material—raucous tales to tell and witty saws to quip. Examples of the latter: “Dying man couldn’t make up his mind which place to go to—both had their advantages: Heaven for climate, Hell for company.” “Faith is believin’ what you know ain’t so.”

Holbrook developed the act before psychiatric patients, school kids, and Rotarians in the Midwest, then launched a polished performance in 1954 as “Mark Twain Tonight!” The stage: Lock Haven State Teachers College in Pennsylvania. Within a few years, he was on “The Ed Sullivan Show” and “The Tonight Show.” He debuted Off-Broadway in 1959, the show hitting Broadway in 1966 when Holbrook won a Tony. He went on to play Clemens’s Twain more than 2000 times from 1954 to 2017 when he retired the act. A record, no doubt, for a single role: 63 years, a decade and a half longer than Clemens himself played Twain.

I met Holbrook in 2003 as part of my research for a 10,000-word profile of Clemens’s daughter, Clara, for the San Diego Reader where I’ve been a staff writer since 1999. I was intrigued by Clara’s story (she died in San Diego at 88), the sole surviving child of Clemens and the controller of his lucrative estate for a half-century. She was the one who said which works of her father would continue to be published and which of the many anti-religious ones would not.

The Clemens’s family saga was a tragedy, known by few as Clemens kept it behind the mask of his tragicomic books and talks. The native Missourian and his wife, Livy, had four children: Langdon who died of diphtheria at 19 months; Suzy (Clemens’s favorite) who died of spinal meningitis at 24; and Jean, the last born, who died by drowning in a bathtub after a seizure at 29. Clara, born in 1874 between Suzy and Jean, outlived everyone.

At 35, Clara married an orchestra conductor, Ossip Gabrilowitsch; soon they had a child, Nina, born six months after her grandfather died. Nina struggled with her mother and her inner demons, an alcoholic while still a teenager, a lifelong affliction. To keep her away, Clara awarded her a stipend of $1500 a month for life. (Nina spent a year in detox at the California State Psychiatric Hospital in Camarillo.)

After Ossip died, Clara moved to California and engaged her love of gurus and mystics, the early New-Age days of Yogananda and Sister Aimee Semple McPherson. On a tip from a seer, she married the dashing Russian émigrè musician, Jacques Samossoud, who claimed to have conducted the world’s greatest orchestras and to be well-acquainted with several U.S. presidents. Nearly all his claims were lies.

But the 50-year-old swept the 70-year-old Clara off her feet. So swept that she redid her will, excising Nina and giving it all to Jacques, a gambling addict as it turned out who, when he died, rolled it over to Clara’s physician, Dr. Seiler. Following her death in 1962, the Clemens estate was contested by Nina and others; the settlement gave Jacques control, his million-dollar debt to it pardoned. The story of Clara, Nina, Jacques, and the fate of Clemens’s copyrighted empire is told here: “I Am Your Loving Daughter, Clara Clemens.”

Hal Holbrook, who in January, age 95, went to the Actor’s Studio in the sky, was an expert on the public Twain and the private Clemens as well as the strain between Sam and Clara, which seems never to have left her. The following remembrance of Holbrook meeting Clara comes from a story he told me in 2003 (we eventually met after one of his Twain performances; he said that he had tough time reading my article columned as it was among the many Reader ads for breast augmentation). He cites Samossoud and his horse-track buddy, Dr. Seiler, who got a chunk of his pal’s fortune, post-probate. Holbrook mentions “An Encounter with an Interviewer.” This sketch Twain wrote in 1874 about a subject who befuddles his interviewer with a raft of non-sequiturs. Perhaps Clara was putting one over on him or else Clemens was masterminding the hoax from the afterlife.

*

I was out here [Los Angeles] in 1959 after I made my first success in New York with Mark Twain. I played the Huntington Hartford Theater, the one on Vine, below Hollywood Boulevard. After one of the shows, Jacques Samossoud and a doctor friend of his [Seiler] came to my show and came backstage to meet me. They were standing in a dark corner, backstage, and I went over to them. They were very mysterious-looking guys. They looked very noncommunicative, staring at me. I didn’t get a friendly feeling from them. They told me that Clara was not in very good health. I remember they used the phrase, “she had good days and she had bad days.”

I’d heard that she wasn’t in good health, and she was living down in Mission Beach. I’d heard about Jacques Samossoud and the way he was spending the money, her money, at the racetrack at Del Mar. I’d heard some pretty unfavorable things about Jacques Samossoud—so I wasn’t prepared to think too much of him. He was very polite. The doctor looked like somebody out of Arsenic and Old Lace.

I had written Clara, because I wanted to come down and meet her, so they had come to check me out. I said, “I’d be willing to drive down on the chance that she’d be [available],” and Jacques said, “If you came down, it depends on the day. I might have to meet you and tell you [that] you can’t see her.” I said, “I’ll take the chance.”

So Jacques said, “She talks to him, you know.” I said, “I beg your pardon.” And he said, “To her father. She talks to him.” And I said, “Oh, I understand. Yes, I know, she’s interested in spiritualism.” “She’s talked to him about you.” I said, Oh yeah?” And he said, “So watch out.” This is a true quote. “So watch out.” Holy mackerel, I thought, I’m in Arsenic and Old Lace. I’m deep in it, so I better just hang on. So I said, “OK, yeah, I will. What does he say about me, do you know?” He said, “So far, it’s pretty good.” I said, “OK. I hope it stays that way.” That’s what I remember about this weird meeting in the dark backstage.

So then I went down to San Diego and found what really was a motel. A nice motel in Mission Beach. I walked in. It was a very airy place, as I remember, sort of colonnaded. Very pleasant. But I was surprised that the daughter of Mark Twain would be living in a motel. Something about it seemed bizarre to me. I figured she’d live in a house. I had had dealings with the estate when my lawyer made a lifetime deal with the Hanover bank. I had some idea of the amount of money coming in. So Jacques Samossoud met me; he was a little more friendly. He said, “She’s doing well today. She wants to see you.” My heart was kind of pounding.

I walked into her bedroom and it was startling. She was lying in bed against at least three pillows. She had three or four books spread out on the bed. She had a great shock of curly white hair. Her eyebrows were even dark. All she needed was a mustache, and she would have looked exactly like her father. The sharp nose. The eyes, dark and piercing. And there was a side table beside the bed that had a lot of bottles of pills and things on it just like his [bed]. I have a pretty rare picture that was given to me of him lying in bed, writing. It was absolutely startling, almost like an imitation.

I was very shy about the whole deal. It’s just my nature. Probably today I would have more weight behind me. Maybe I would have felt I had more of a right to ask certain questions. Which I was reticent to ask because I was very, very respectful. I was always very respectful of my attachment to Mark Twain, and I still am. I’m much more mature about it now, but in those days, I was still young. I was very respectful to the point of not wanting to bother or hurt anybody. I’m not a gossip monger.

She was very sweet, very alert, very friendly. “Hello Hal,” she said, as if we knew each other. “Draw up a chair.” Samossoud had come in and moved things around so she could see me. I sat down, but I can’t remember what I said, something like, “It’s so wonderful to be able to meet you.” Maybe she said, “I’ve heard a lot about you.” She may have said Dorothy [a friend of her father’s] wrote her. I can’t remember. But it was nice talk.

She asked me about myself. I asked a few questions about her father, but I was very nervous I guess about asking any terribly interesting questions about him. I would have loved to have said, “I hear that you and your father didn’t get on very well.” If I had to go through it again—I was a fool. I had an opportunity to find out certain things that have been written about. People have written about those last years. Quite obviously she was not his favorite. Quite obviously she was a very strong-willed person. And certainly so was he. He was a true artist. He was a genius artist. Tremendously sensitive man, way more sensitive than anybody would think just by looking at him. He was probably an extremely difficult person to be around some of time. And he was a star. I don’t like the word self-centered because it reduces the greatness of his soul and his perceptions to say that he was self-centered.

But he was the great shining light—obviously—any place he went. His children—it’s very difficult on children. And I think it was very difficult on Clara. And then that starts to work both ways. Because a certain resentment develops on one side, it boomerangs back on the other person. And if that other person has strong sensitivities, it can upset that person’s emotional metabolism. And then you’ve got a maladjustment in a relationship. I think in very simple terms that’s probably what happened with Clara.

But, anyway, she didn’t want to talk about her father. I couldn’t get her to talk about her father. I tried to get her to talk about him in a gentle way, leading the conversation, and she would steer it away, to me. And then she finally said, “I have an idea for you Hal.” I said, “Really, what is that?” “I have an idea what you should do.” I said, “What?”

“I see you doing a performance as Jesus Christ.” I said, “Really. Gosh, I don’t know.” “I think it would be wonderful,” she said. “You could bring His teachings and His wonderful philosophy to the world.” And I said, “I don’t know if I could really do that. Would anybody want to come and see it?” “Oh, I think it would be very popular with people. I think they would really want to see it.” I said, “I don’t know whether I’m—I can’t imagine myself, you know—” “Oh,’ she said, “I think you could do it Hal, I really do.” I said, “Well”—and I’m thinking to myself, good grief, is she crazy? I didn’t want to insult her. She was very lovely and sweet about it.

[And serious? I asked, finally interrupting the tale.]

And serious. I think she was serious. Unless this was one of those great Mark Twain put-ons. Like “An Encounter with an Interviewer.” You’ve just struck on an idea that never occurred to me. Maybe she was doing “An Encounter with an Interviewer.” Now you’ve struck it. That’s the only explanation I could possibly think of for her saying that I should do Jesus Christ. If she wasn’t doing it, her father was doing it through her. Her father was putting me on.

Samossoud and the doctor had probably wanted to say, “She wants you to play Jesus Christ,” so be ready for this. Samossoud had left the room; he didn’t want any part of it. Then he picked me up on the way out. “How was it?” he said.

When I look back on this incident—and I was a grown man—my reluctance to be nosy with people, my fear of hurting someone’s feelings, prevented me from finding out quite a few things. I could have said, “Are you kidding, ma’am?” She might have smiled and said, “Why, do you think I’m kidding?” I mean, come on—Jesus Christ? I’m only an actor.