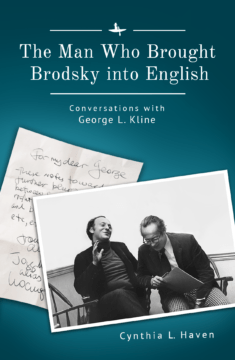

Maxim D. Shrayer talks to Cynthia L. Haven about her new book, The Man Who Brought Brodsky into English: Conversations with George L. Kline

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

I studied with Joseph Brodsky at the University of Michigan—his first port of call in the U.S. It was psychological and aesthetic jolt, like sticking your finger into a light socket. And yes, we memorized hundreds of lines of poetry in his classes.

For many of us, Brodsky’s Selected Poems in 1973 was a radical reorganization of what poetry can be and mean in our times. However, I didn’t connect with the book’s translator, George Kline, until after I published Joseph Brodsky: Conversations in 2002. George and I stayed connected with Christmas cards and occasional phone calls. But we’d never actually met face to face—so I had no real sense of his age, until in late 2012, when he mentioned that he was almost 92.

George was a champion for Joseph Brodsky and his poetry—many people know that, but many don’t know that he was also a wise and kindly supporter of poets, Slavic scholars, and translators everywhere. He had never given a full account of his collaboration with the Russian-born Nobel poet, however, and I realized time was running out. So we began recording conversations.

His health was failing, and our talks became shorter and more infrequent. Towards the end, he urged me to augment our interviews with his articles, correspondence, and papers, reconstructing a portrait of his collaboration with Brodsky. George died in 2014.

His death was a huge loss for the field of Russian studies. But for you and your work, unimaginable… What was it like continuing without him?

The effort was more than a jigsaw puzzle. I felt like I was carefully gluing together a model airplane to take us to another world – a world that began with Soviet Leningrad in the 1960s where George met the young red-headed poet and ended with the poet’s death at his home in Brooklyn in 1996. More than that, it was the world that Brodsky created with his poems, which they both inhabited.

What role did Kline play in Brodsky’s life and literary career, and what did Brodsky mean to Kline?

George translated more of Brodsky’s poetry into English than anyone else, with the exception of Brodsky himself. Poetry was an avocation for George, but my goodness—look at how George evolved as a translator from his early “Elegy for John Donne” to his stunning translation of “The Butterfly” a decade later!

Joseph Brodsky was the adventure of George Kline’s life, I think. He found himself lunching with world poets and attending the Nobel awards ceremonies in Stockholm. But it wasn’t his world or natural habitat, and George knew that.

Incidentally, many people also do not know that Kline was a highly regarded Slavic scholar, writing about Russian religion and philosophy. His obituaries in journals focused on that work, not his work with Joseph Brodsky!

How would you describe Kline’s approach to translating Brodsky? Why do you think Brodsky—who at times wasn’t easy to please—appreciated Kline’s translations?

It was an unlikely partnership, in temperament and training, but one trait they shared was a commitment to maintaining the formal scheme—rhyme, meter, and so on—of the original poem.

George was also insistent that nothing be added to or subtracted from the poem. Of course, Joseph changed his poems freely, but that was the poet’s prerogative—not the translator’s.

I said that George evolved as a translator—well, Brodsky changed, too. He was extremely lucky to have found Kline early in his poetic career. But as he became an internationally recognized writer, he had a greater range of translators to choose from, some of them outstanding poets in their own right: Anthony Hecht, Richard Wilbur, Derek Walcott among them. George sometimes felt sidelined, inevitably. But George had a full, rich life of his own.

Where do you think Brodsky’s poetry, often described as “metaphysical,” found common ground with Kline’s own philosophical interests and pursuits?

They both had a sacred vision of the world—and of the word. Both defy easy categorization. Kline was loosely “Unitarian,” Brodsky caught or suspended between Judaism and Christianity. At one point he described himself as a Calvinist, at other times his vision seemed almost Catholic—given his love of Italy, how could it be otherwise?

George remembers seeing a volume of Nikolay Berdyaev on Brodsky’s desk when he first visited the poet’s his Leningrad room—The Philosophy of the Free Spirit. That may indicate his turn of mind as well. Another point of connection with the philosophy professor.

One poem Kline loved, and that he unfailingly presented at readings, was Brodsky’s “Nunc Dimittis.” It’s Jewish and Christian, illustrating the transition between the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, both powerfully represented. The dying Simeon and the infant Christ, who grows in cosmic and historical dimensions. That poem alone shows the fusion of those two sides of himself.

The years since his early days have seen many more translations. How do you feel about more recent English retranslations of Brodsky’s poems?

The more the merrier. Kline himself wanted to see more translations of Brodsky’s work, he was a translation “liberal.” There are always trade-offs in translation. He wanted to see what others would do. Brodsky is said to be untranslatable. If so, the best we can do is have multiple translations and triangulate meaning. As English speakers living in 21st century America, we also need to have a better understanding of the art of translation—and its necessary choices, sacrifices, limits. That’s what this book is for.

Finally, Cynthia, if one were to play devil’s advocate or dismiss totalizing explanations by suggesting that Kline wasn’t the only person who “brought Brodsky into English”—there were after all W.H. Auden and Carl Proffer—what might your response be?

Oh heavens! I would never wish to diminish the legacy of either of those remarkable men. Both are pivotal in Brodsky’s story. I’m delighted that mine is the second book—after Ellendea Proffer Teasley’s Brodsky Among Us—to appear in the book series you curate for Academic Studies Press. Both the Proffers had vital roles in Joseph’s life and work. There should be a statue to them in Russia. I’ve said that before.

Carl Proffer brought Brodsky to America, meeting him in Vienna, changing the poet’s plans and planes, diverting him to the U.S., and finagling a University of Michigan appointment for the young man who had dropped out of school at 15. Joseph himself said that Carl Proffer “was simply an incarnation of all the best things that humanity and being American represent.”

W.H. Auden’s foreword in Selected Poems was critical. It launched Brodsky’s first important book in the West. It also began a personal friendship that was foundational for Brodsky as a poet and a human being. But Auden didn’t bring the poems into English.

George made a home for Joseph in the English language, beginning in the first days of his exile, as they revised poems together at Goose Pond in the Berkshires. George Kline is behind the Selected—not only in his translations, but in getting it published at a high level where it would get the world attention it merited.

Don’t forget that when Kline heard about the Nobel prize on the radio, he called London to offer his congratulations to Brodsky. The poet replied, “And congratulations to you, too, George.”

Cynthia, congratulations to you on the book, and may it have a long life.

***

Maxim D. Shrayer, a professor of Russian, English, and Jewish Studies at Boston College and a Guggenheim Fellow, is the author of over fifteen books, including the internationally acclaimed memoirs Waiting for America and Leaving Russia. Shrayer’s most recent book is Of Politics and Pandemics: Songs of a Russian Immigrant.

Cynthia L. Haven is a National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar and author of 2018’s Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, the first-ever biography of the French theorist. Her Joseph Brodsky: Conversations was published in 2003. Her Czesław Miłosz: A California Life is forthcoming.