by Ethan Seavey

The end of the pandemic is far from near. The end of the American epidemic is far from near, too, but for those of us who made the decision to get one of three miracle vaccines, our COVID story is slowly wrapping up.

The COVID world was lonely, hidden, distrustful, terrifying, and endless. The COVID world was online, which excited me because then, I would’ve happily spent all day online. That changed.

Until there was a completed, ready-to-eat vaccine I believed we would be stuck in this digital alternate universe for five years. When every news channel boasted the efficacies of the new vaccines, I believed it’d be years before I got one, years before I’d have to worry about returning to the old world, the one so foreign to me now.

And now: it’s here. It’s knocking on the door, hard. I’m vaccinated and I’m supposed to jump back out into that real world, and that fills me with anxiety. I should’ve seen dozens of friends I promised to see, but now that I’m able, I can’t find the energy. I should’ve been a miserable unpaid intern four times by now, but I can’t get an e-mail back. I should be moving forward, and I can hope that I’m looking at that glorious summit by now, but I’m more comfortable thinking it’s just another false peak.

My future is made up of several fantasies. There’s one where I see myself a successful writer—that is: meeting my basic needs—and raising a happy family with the man I love. Read more »

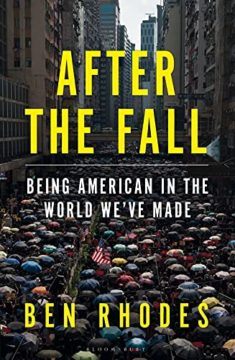

Many of us read with interest Ben Rhodes’ insider account of his time as a speech writer and advisor to Barack Obama during that historic presidency in his book The World as It Is: Inside the Obama White House. There were suggestions of his displeasure at some aspects of US politics in that publication, as for example the racism he thought Obama was subjected to while in office. His new book After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, goes further and is a clearer articulation of his concern about US and international politics. The conclusions he draws could be viewed as a personal coming of age in his understanding of the impact of American foreign policy on the world, and indeed experiencing and confronting more realistically, the ‘darker’ angels in US domestic politics.

Many of us read with interest Ben Rhodes’ insider account of his time as a speech writer and advisor to Barack Obama during that historic presidency in his book The World as It Is: Inside the Obama White House. There were suggestions of his displeasure at some aspects of US politics in that publication, as for example the racism he thought Obama was subjected to while in office. His new book After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, goes further and is a clearer articulation of his concern about US and international politics. The conclusions he draws could be viewed as a personal coming of age in his understanding of the impact of American foreign policy on the world, and indeed experiencing and confronting more realistically, the ‘darker’ angels in US domestic politics. In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a

In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a  One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness,

One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness,

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such  Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable.

Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable. A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.