by Thomas O’Dwyer

1066 And All That, a sly rewrite of the history of England, was published in 1930 and became a perennial bestseller. Its subtitle was A Memorable History of England, Comprising All the Parts You Can Remember, Including 103 Good Things, 5 Bad Kings and 2 Genuine Dates. Written by W. C. Sellar and R. J. Yeatman, the book, in the words of one critic, “punctured the more bombastic claims of drum-and-trumpet narratives … both the Tory view of ‘great man’ history and the pieties of Liberal history.” There is no connection, literary or otherwise, between this satirical non-fiction and 2666, the weighty novel by Chilean author Roberto Bolaño, published after his death from liver failure in 2003 at the age of 50. However, that phrase “all the parts you can remember” triggered an association when I found a battered copy of Bolaño’s novel among some old books discarded on a park bench. But it was a half copy — the covers and last 100 pages of the 900-page tome were missing. “The parts you can remember” reminded me of my spotty knowledge of Latin American writing picked up in those faddy years following the so-called Boom in the region’s literature from the 1950s to the 1970s. In the English-reading world, any serious book-lover felt obliged to mention, at the drop of a dinner-party conversation, Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Isabel Allende, Octavio Paz, or Carlos Fuentes. The ultimate one-upmanship would have been to claim reading one of the authors in Spanish, but in my years in England, I never heard anyone do so. “You don’t read Borges,” one friend mocked. “You read his translator. That’s like washing your feet with your socks on.” Read more »

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

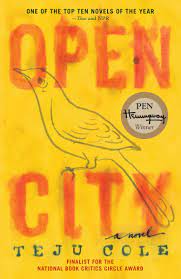

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?

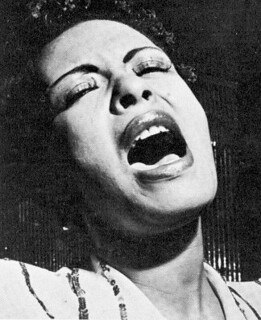

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat? Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace. Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this? The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.