by George Barimah, Ina Gawel, David Stoellger, and Fabio Tollon*

When thinking about the claims made by scientists you would be forgiven for assuming that such claims ought to be true, justified, or at the very least believed by the scientists themselves. When scientists make assertions about the way they think the world is, we expect these assertions to be, on the balance of things, backed up by the local evidence in that field.

The general aim of scientific investigations is that we uncover the truth of the matter: in physics, this might involve discovering a new particle, or realizing that what we once thought was a particle is in fact a wave, for example. This process, however, is a collective one. Scientists are not lone wolves who isolate themselves from other researchers. Rather, they work in coordinated teams, which are embedded in institutions, which have a specific operative logic. Thus, when an individual scientist “puts forward” a claim, they are making this claim to a collection of scientists, those being other experts in their field. These are the kinds of assertions that Haixin Dang and Liam Kofi Bright deal with in a recent publication: what are the norms that govern inter-scientific claims (that is, claims between scientists). When scientists assert that they have made a discovery they are making a public avowal: these are “utterances made by scientists aimed at informing the wider scientific community of some results obtained”. The “rules of the game” when it comes to these public avowals (such as the process of peer-review) presuppose that there is indeed a fact of the matter concerning which kinds of claims are worthy of being brought to the collective attention of scientists. Some assertions are proper and others improper, and there are various norms within scientific discourse that help us make such a determination.

According to Dang and Bright we can distinguish three clusters of norms when it comes to norms of assertions more generally. First, we have factive norms, the most famous of which is the knowledge norm, which essentially holds that assertions are only proper if they are true. Second, we have justification norms, which focus on the reason-responsiveness of agents. That is, can the agent provide reasons for believing their assertion. Last, there are belief norms. Belief norms suggest that for an assertion to be proper it simply has to be the case that the speaker sincerely believes in their assertion. Each norm corresponds to one of the conditions introduced at the beginning of this article and it seems to naturally support the view that scientists should maintain at least one (if not all) of these norms when making assertions in their research papers. The purpose of Dang and Bright’s paper, however, is to show that each of these norms are inappropriate in the case of inter-scientific claims. Read more »

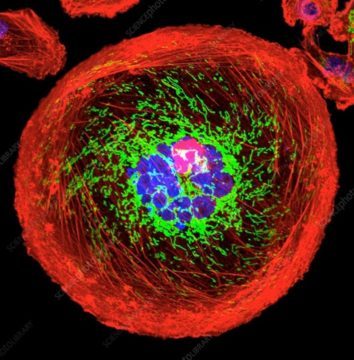

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?

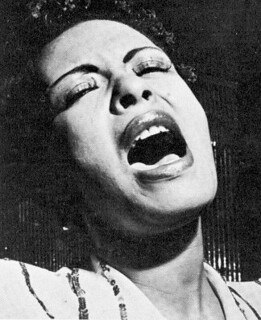

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat? Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace. Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Santiniketan in my childhood used to attract a lot of foreign scholars, artists and students, which was a boon to a young stamp-collector like me. Every day the sorting at the small post office was completed by mid-morning and many of the residents used to come and collect their mail themselves. I, along with a couple of other children, used to wait there for the foreigners to collect their mail. As soon as one was spotted, we used to scream “Stamp! Stamp!”; they obliged us by tearing off the stamps in their envelopes. Soon I had a thick album of foreign stamps. I used to linger wistfully over every stamp and imagined things about those distant foreign lands. (I remember Swiss stamps said only ‘Helvetia’ on them, which I could never find in the only world map I had at home).

Santiniketan in my childhood used to attract a lot of foreign scholars, artists and students, which was a boon to a young stamp-collector like me. Every day the sorting at the small post office was completed by mid-morning and many of the residents used to come and collect their mail themselves. I, along with a couple of other children, used to wait there for the foreigners to collect their mail. As soon as one was spotted, we used to scream “Stamp! Stamp!”; they obliged us by tearing off the stamps in their envelopes. Soon I had a thick album of foreign stamps. I used to linger wistfully over every stamp and imagined things about those distant foreign lands. (I remember Swiss stamps said only ‘Helvetia’ on them, which I could never find in the only world map I had at home).

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this? The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also. The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers.

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers. In the beginning, the god of the

In the beginning, the god of the