by David J. Lobina

by David J. Lobina

Just as Donald Trump fires the commissioner of the Bureau of Labor [sic] Statistics because he didn’t like the data they reported, I am reminded of two things: Michael Gove’s infamous quote about experts during the lead up to the so-called Brexit referendum, when he was Lord Chancellor in the UK government, and my own attitude regarding experts.[i]

‘I think the people of this country have had enough of experts with organisations with acronyms saying that they know what is best and getting it consistently wrong’, said Gove then, and as in the case of Trump, the remark was in the spirit of dismissing data and analyses that didn’t fit his policy positions. In this case, what Gove did not like was the prediction that the UK would be worse off outside of the European Union – a rare win for economists, in fact, as it happens.

Indeed, economists tend to be many people’s idea of a bad expert, including mine, though not because (some) economists fail so often with their forecasts, but on account of how conceptually shaky I have always found economic modelling in general. This brings me to my own attitude towards experts, which is basically an anarchist take on the issue. In short: show me the details of the conclusion for this or that claim and I will attempt to understand the logic of it to the best of my ability in order to then make up my own mind about it.[ii]

The devil is in the details, of course. When it comes to climate change, for instance, the science is too foreign and the details too complex for me to come up with a reasonable conclusion, and in this case at least I have to go with the scientific consensus of 97% of the field – namely, in case anyone is unaware, that the Earth has consistently been warming up since the Industrial Revolution, that the rate of this warming-up is unprecedented, and that this is mostly the result of human activity (in particular, the burning of fossil fuels; see here).

This is not to say that some orbiting issues around the consensus on climate change cannot be evaluated by lay people. Read more »

Hebrew or English?

Hebrew or English? Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025.

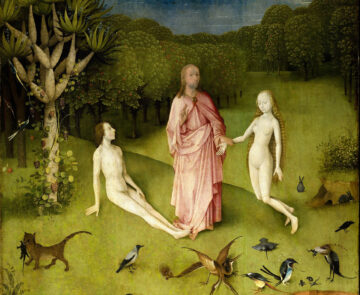

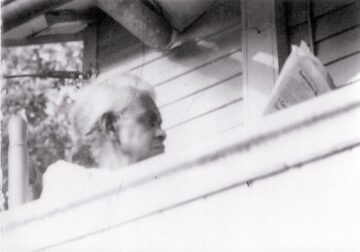

Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025. reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.