by Dilip D’Souza

The star Proxima Centauri has been in the news this August. One reason is actually as a sort of corollary, a side mention. Proxima Centauri, Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B are the stars that make up the star system we know as Alpha Centauri: a triple star system, though without a telescope, we see it as one star.

Now such a system is fascinating enough by itself, but the real reason Alpha Centauri interests us Earth folks is that it is the closest “star” to us apart from our Sun – about 4.5 light years away. And of the three, Proxima Centauri is actually the closest. And, as a red dwarf, it’s the smallest, the coolest, the … in fact, deadest of the three. That’s because red dwarf stars are close to the end of their lives.

This August, a team of astronomers used the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to discover a planet orbiting Alpha Centauri A. Not only that, it looks like the planet is in Alpha Centauri A’s “habitable zone”, meaning it’s at least possible there might be life there. (I wrote about that discovery here.)

Why is the Alpha Centauri A planet a reminder of Proxima Centauri? Because while this planet is new to us, we’ve known for a few years now that three planets orbit Proxima. Which means that of the nearly six thousand so-called “exoplanets” – planets outside our Solar System – we know of today, these three are the closest to us. What’s more, one of them is in Proxima’s habitable zone. (That particular exoplanet prompted this column, but it returns only near the end.)

It should be no surprise that there are scientists who put those facts together and think: Can we humans get there? Can we live there? Read more »

Hebrew or English?

Hebrew or English? Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025.

Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025. reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

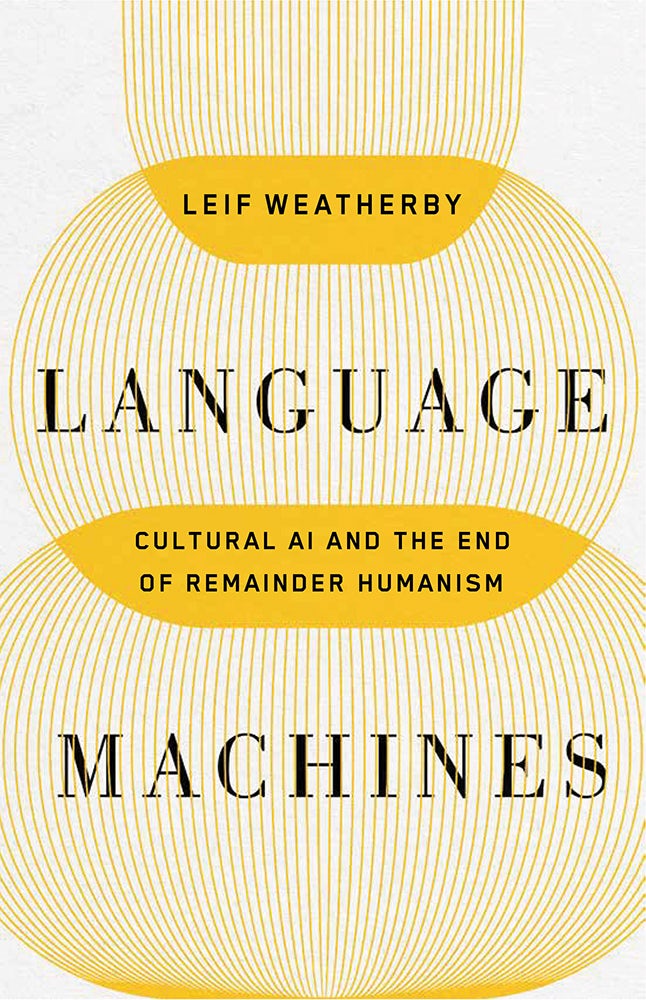

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.