by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Shortly after my arrival at Cambridge I struck up a warm friendship with a very bright young faculty member, Jim Mirrlees (who was to get the Nobel Prize later), recently returned from a stint of research in India. (Although he was a high-powered theoretical economist, he had what seemed to me an almost religious/moral fervor for doing something to help poor countries). Even more than Frank Hahn, he got involved in the theoretical analysis in my dissertation, and helped me in making some of the proofs of my propositions simpler and less inelegant.

Shortly after my arrival at Cambridge I struck up a warm friendship with a very bright young faculty member, Jim Mirrlees (who was to get the Nobel Prize later), recently returned from a stint of research in India. (Although he was a high-powered theoretical economist, he had what seemed to me an almost religious/moral fervor for doing something to help poor countries). Even more than Frank Hahn, he got involved in the theoretical analysis in my dissertation, and helped me in making some of the proofs of my propositions simpler and less inelegant.

One time I had found an error in the proof of a proposition in a widely-read article on Growth Theory recently published by Hahn (jointly with Robin Matthews). I was pretty sure that their proposition was correct, but not the way they proved it. The morning I showed this to Hahn in a Department common room, he and several others got busy on the blackboard with constructing an alternative proof, but all of them failed. At one point Mirrlees entered the room and asked what was going on. He looked from a distance for a few minutes at the futile attempts on the board, and then proceeded to another part of the board, and wrote down a neat proof. Everyone in the room clapped. His method of proof also gave me an idea in proving some propositions later in my dissertation.

In Cambridge your supervisor cannot be your examiner, the dissertation has to be approved by two examiners, one internal (to the university), the other external. Mirrlees eventually was appointed my internal examiner. Incidentally, later Mirrlees also became the internal examiner on Kalpana’s dissertation, even though her work was not on theory, but on Indian agriculture. I used to tell Jim that while other people had a family doctor, we had in him a family examiner. Whenever he and his first wife Gill (who I think was a school teacher) went to a dinner party, and economists indulged in their bad habit even there of talking technical economics, I used to notice Jim’s sweet gesture in valiantly trying to whisper into Gill’s ears translations of those technical arguments in more comprehensible language. (He later lost Gill to cancer). Read more »

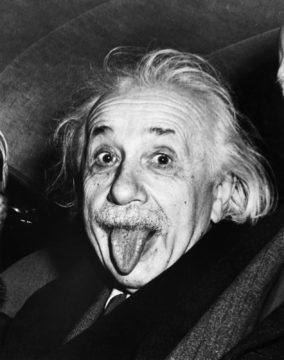

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021.

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021. If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

The well-known counterintuitive Monty Hall problem continues to baffle people if the emails I receive are any indication. A meta-problem is to understand why so many people are unconvinced by the various solutions. Sometimes people even cite the large number of the unconvinced as proof that the solution is a matter of real controversy, just as in politics an inconvenient fact, such as the ubiquity of Covid-19, is obscured by fake controversies.

The well-known counterintuitive Monty Hall problem continues to baffle people if the emails I receive are any indication. A meta-problem is to understand why so many people are unconvinced by the various solutions. Sometimes people even cite the large number of the unconvinced as proof that the solution is a matter of real controversy, just as in politics an inconvenient fact, such as the ubiquity of Covid-19, is obscured by fake controversies.

It had been a long time since I thought about lawns. I don’t mean in a grand philosophical sense, or the stoned contemplation of a single blade of grass. I mean thought about them at all. Before moving to Mississippi we had lived in Vancouver for 13 years, where we felt lucky to have a place to store our toothbrushes and maybe an extra pair of slacks; we really hit the jackpot when we acquired a postage-stamp-sized balcony on which we could murder tomato plants. Actual yards were out of the question for anyone who hadn’t bought a house on the west end of town 30 years ago; by the time we moved to Vancouver in 2006 as a tenure-track assistant professor and a trailing-spouse adjunct, it was already clear that we would never own a lawn.

It had been a long time since I thought about lawns. I don’t mean in a grand philosophical sense, or the stoned contemplation of a single blade of grass. I mean thought about them at all. Before moving to Mississippi we had lived in Vancouver for 13 years, where we felt lucky to have a place to store our toothbrushes and maybe an extra pair of slacks; we really hit the jackpot when we acquired a postage-stamp-sized balcony on which we could murder tomato plants. Actual yards were out of the question for anyone who hadn’t bought a house on the west end of town 30 years ago; by the time we moved to Vancouver in 2006 as a tenure-track assistant professor and a trailing-spouse adjunct, it was already clear that we would never own a lawn.