by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

At MIT I had my initiation into a breathless pace of academic activity that was quite different from the pace I had seen elsewhere until then. The whole place was a dynamo of research activity, you could almost hear the hum and feel the energetic throb of multiple high-powered brains at work. While teaching was an important part of daily activity and it often fed into research, it was research where the main action was. Later I found out this was more or less the case in other top departments in the country, but at MIT I had my first experience. There was the thrill of thriving at the frontier of your subject, you saw the frontier visibly moving from one seminar to another, from one widely-cited journal article to another, you had to run fast even to remain at the same place, and while the competition and the race were invigorating, you could also see the jostling and the occasional hustle.

At MIT I had my initiation into a breathless pace of academic activity that was quite different from the pace I had seen elsewhere until then. The whole place was a dynamo of research activity, you could almost hear the hum and feel the energetic throb of multiple high-powered brains at work. While teaching was an important part of daily activity and it often fed into research, it was research where the main action was. Later I found out this was more or less the case in other top departments in the country, but at MIT I had my first experience. There was the thrill of thriving at the frontier of your subject, you saw the frontier visibly moving from one seminar to another, from one widely-cited journal article to another, you had to run fast even to remain at the same place, and while the competition and the race were invigorating, you could also see the jostling and the occasional hustle.

I was amazed how well-informed people were about who was doing what in which department in the country, who was pushing the (research) boundary where, which young faculty you had to attract before others grab them, what was the going market rate for a particular ‘hot-shot’ scholar, who was having an offer from which top department, and so on. (This reminds me of a phone conversation I had with the Dean of a top east-coast university much later when I joined Berkeley. This Dean wanted to know if I’d be interested in joining his University. Before he went any farther, I told him that I had only recently settled down in Berkeley, both my wife and myself liked the place, and just bought a house, and so I’d not be interested in moving. He talked for a while and then gave up. But before ending the conversation, I think he took pity on me and gave me a bit of ‘personal advice’. He said he could see that I was not yet used to the system in the American academic market. “When somebody offers you a job”, he said, “you don’t say ‘no’ even before I told you the salary I was going to offer you, which I am sure is much higher than what Berkeley is paying you. Even if you are ultimately not really interested, you try to get all the information, take the time, bargain with your Department, and get a raise for yourself”).

At the MIT Department those days the most revered leader clearly was Paul Samuelson, who every day at noon would preside over the lunch table at the Faculty Club in the top floor of the building. At the table, he’d often entertain us drawing upon his spectacular collection of stories and gossip, not just about economists, but often about physicists and mathematicians. To Paul there was a clear hierarchy of disciplines. It was visibly demonstrated to me one day when we took a visiting English friend who wanted to meet Paul. We told Paul that he’d be interested to know that this friend had done his degree in Astrophysics, but now he was thinking of moving to Economics. At this Paul immediately said, putting his hand above his head, “Astrophysics, then Economics (he lowered his hand to his chest level), what next? Theology? (moving his hand to the knee level). Read more »

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom. My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.

Everyone knows—or should know—how burdensome a pregnancy is on a woman. It’s especially hard now if you live in Texas where a fetal heartbeat detected at six weeks means by law the woman cannot terminate her pregnancy; she must carry it to term. The burden of having a child, whether planned for or forced, is made worse by the financial responsibility of raising that offspring, for parents and families, through childhood and adolescence, the next eighteen years. Would any man argue that such a load, for poor women in particular, is among the toughest things she’ll ever face?

Everyone knows—or should know—how burdensome a pregnancy is on a woman. It’s especially hard now if you live in Texas where a fetal heartbeat detected at six weeks means by law the woman cannot terminate her pregnancy; she must carry it to term. The burden of having a child, whether planned for or forced, is made worse by the financial responsibility of raising that offspring, for parents and families, through childhood and adolescence, the next eighteen years. Would any man argue that such a load, for poor women in particular, is among the toughest things she’ll ever face?

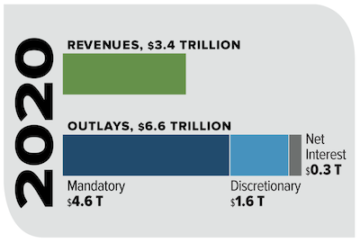

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide.

Someone described the US Federal Government as a huge insurance company that has its own army. There’s real truth to that description. The vast majority of the federal budget goes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Those entitlement programs take up about 65% of the federal budget, while the military takes up about 11% of the federal budget. The interest on the federal debt takes up another 8%, leaving only about 15% for “discretionary” spending. The money spent on the military is also considered discretionary but given our vast reach with hundreds of military bases in dozens of countries, voting to reduce the military budget much would be political suicide. Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”

Last year the federal government took in $3.4 trillion of taxes and spent $6.6 trillion, nearly twice its revenues. A trillion dollars is a vast, almost inconceivable amount of money. And yet our government spends money in such cosmic sums that congresspeople and senators toss around the word trillion as if it’s the cost of a night’s stay in a Motel 8. Perhaps the two best quotes about casually spending and losing vast sums of money come from the late Texas oilman Nelson Bunker Hunt. When asked about his $1.7 billion losses after he tried to corner the silver market, he replied, “A billion dollars isn’t what it used to be.” Then at a congressional hearing when asked about his net worth, Hunt replied, “I don’t have the figures in my head. People who know how much they’re worth aren’t usually worth that much.”  Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.

Tanya Goel. Mechanisms 3, 2019.