by David Oates

A scar is a shiny place with a story.

A scar is a shiny place with a story.

A skink is a story you could never imagine.

It leaves a bright streak across your vision and an after-image you might notice even years later, neon greeny blue flashing amidst weed and dry stone and buckbrush and bending sumac trees. Our mountains were called the San Gabriels, a name somehow just barely noble enough for these creatures. In their foothills skinks appeared to us like tiny fragile dragons, fully astonishing, sinuous, and menacing. They liked to writhe. Would bite, the bony jaws clamping onto a fingertip, a ten-year-old’s screaming terror – until it was seen that the grim little mouth could not break the skin. The beast just hung on there, flailing, until screams turned to laughter and showing off, “Lookit, lookit, lookit. . .!”

If someone tried to tell you about skink, it would sound like a lie, an exaggeration. Just seeing it certainly outstripped the lame awe-mongering of, for example, Superman comic books.

And made you wonder what else might be out there.

When my mother’s voice rose up on a summer eve, and we had been allowed to play outside after dinner. When I noticed the mourning doves silhouetted on telephone wires above us, repeating and repeating their strangeness and sadness. Perhaps I would see her standing in the illuminated doorway, in the warm air full of chaparral scent drifting downhill off the mountains. Her voice calling then falling still, while the blue-black sky gathered evening under itself. And us in it.

Then the boys would come barging back into the house, and the mood would break and be replaced with all the reassuring commotion we could muster.

Once in a while my mom would accidentally back into the truth, like hitting something in the garage with her fender. “Well, we raised them by hand, so. . .” This was not really apology, just what we were: three dusty, slightly used boys, with dents here and there and unstraightened teeth. Read more »

When I first attended the occasional Harvard-MIT joint faculty seminar I was dazzled by the number of luminaries in the gathering and the very high quality of discussion. Among the younger participants Joe Stiglitz was quite active, and his intensity was evident when I saw Joe chewing his shirt collar, a frequent absent-minded habit of his those days. Sometimes one saw the speaker incessantly interrupted by questions, say from one of the big-name Harvard professors, Wassily Leontief (soon to be a Nobel laureate). At Solow’s prodding I agreed to present a paper at that seminar, with a lot of trepidation, but fortunately Leontief was not present that day.

When I first attended the occasional Harvard-MIT joint faculty seminar I was dazzled by the number of luminaries in the gathering and the very high quality of discussion. Among the younger participants Joe Stiglitz was quite active, and his intensity was evident when I saw Joe chewing his shirt collar, a frequent absent-minded habit of his those days. Sometimes one saw the speaker incessantly interrupted by questions, say from one of the big-name Harvard professors, Wassily Leontief (soon to be a Nobel laureate). At Solow’s prodding I agreed to present a paper at that seminar, with a lot of trepidation, but fortunately Leontief was not present that day.

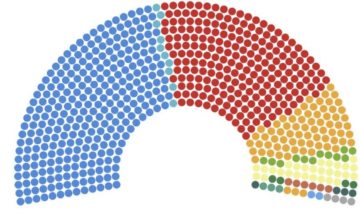

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?

My books are arranged more or less the way a library keeps its books, by subject and/or author, although I don’t use call numbers. I also have various piles of current and up-next and someday-soon reading. In addition, I have a loose set of idiosyncratic categories that guide my choice of what to read right now, out of several books I’m reading at any given time. I choose books for occasions the way more sociable people choose wines to complement their menus.

My books are arranged more or less the way a library keeps its books, by subject and/or author, although I don’t use call numbers. I also have various piles of current and up-next and someday-soon reading. In addition, I have a loose set of idiosyncratic categories that guide my choice of what to read right now, out of several books I’m reading at any given time. I choose books for occasions the way more sociable people choose wines to complement their menus.

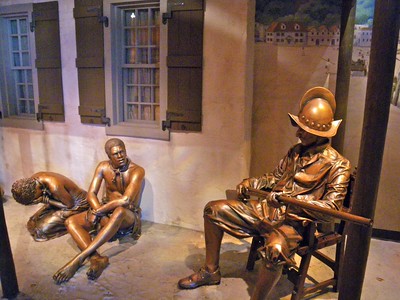

What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are.

What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are. Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.