by Paul Orlando

Louise Bourgeois was an artist based out of New York and most often thought of as a sculptor. My favorite of her works was called Maman — a giant spider that I walked under many times while visiting the Tate Modern.

Louise Bourgeois was an artist based out of New York and most often thought of as a sculptor. My favorite of her works was called Maman — a giant spider that I walked under many times while visiting the Tate Modern.

She also used to hold an artists’ salon out of her home in Manhattan.

Her salon was famous both for it being her salon but also because she continued it for over 30 years. I’m at an age where doing something for over 30 years is just becoming understandable. So I thought I’d share my experience attending.

Years ago I was part of an artist group and learned about the salon. I had never experienced such a thing before, which seemed fitting more with old European novels than my life in New York. But one by one over a few years, different artist friends in the group told me about their experience at Bourgeois’ salon. Good and bad (where criticism was tough), but mostly good.

Eventually, I resolved to try it myself.

The next day I went to my phone, looked at the number to call, and let a year go by.

The next year, when I got up the nerve, I reached Bourgeois’ assistant and was told that the salon was already full for that week.

I waited another six months. Same result.

A year went by with only occasional thoughts of calling again.

Finally, one day I picked up the phone and with minimal worry, called, was connected, told to arrive that Sunday at 3pm, and of course that Louise liked chocolate.

I packed photos of my work. Light-illuminated plastic bags and my efforts to catalog people whose moles and freckles happened to look like celestial constellations. I left early, took the subway, walked to the address on West 20th Street, passed by a couple times, and then went to a nearby high-end chocolate shop.

Among the luck I had that day was that the chocolate shop mis-packed my box of chocolates so that they were jumbled. Realizing this, they made me a second box for free. So I ate the jumbled pieces myself.

Fueled with sugar I went back to West 20th. By then there was a small line of people outside the brownstone’s entrance. I joined the line and talked with the others. A few moments later a door opened and we went up the stoop and into a dim room packed floor to ceiling with books, paintings, and mismatched furniture.

There was a low table with a large, interesting collection of bottles of alcohol.

We poured ourselves glasses of every item, admired the books, the paintings, and talked about our work.

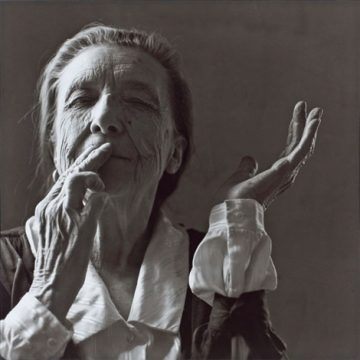

Eventually, Bourgeois entered the room. She walked with two canes, wore two sweaters (in the middle of summer), a long skirt, and a beret. She sat down heavily behind a desk at one side of the room.

After a brief greeting she said nothing.

Eventually her assistant, who sat to the side and slightly behind her, motioned for the first one of us to approach.

The first artist stepped up and immediately made the faux pas of mentioning the recent death of Bourgeois’ friend Robert Rauschenberg. The assistant made the “cut it out” sign behind Bourgeois’ head and that conversation starter died too. The artist then showed a couple paintings to a modest reaction.

Next was an artist visiting from France. He brought a ping pong paddle carved into the shape of his country. Bourgeois picked it up and set it down. He showed some other items. They exchanged some quiet words in French. Eventually it became apparent that he should sit back down, and there was a slight pause.

It was time for the next person to approach. As I recall, this woman also brought a couple paintings. A similar scene.

Then there was a woman who approached with a sketchbook. She flipped through pages of the book showing similar looking drawings on each page. “Every day when I wake up the first thing I do is I draw a hole,” she said. Now this was interesting. Bourgeois picked up the book, silently flipped through the pages, and said some words I don’t remember. I later flipped through that book myself and loved it.

As a recall, I was up next. I had made 11″ x 14″ enlargements of my photos to make them easier to see. I first showed a few images of the bags, which focused on the light and detail on the wrinkles of each one. Next I showed a photo of the freckle constellations that I was gathering at the time. Bourgeois asked how I found people with those marks and I explained that they wrote in to me online. Her assistant actually pulled up the website, which seemed so out of place in our current environment. Bourgeois held a couple of my photos in her hands, looked at them intently, looked at me, grunted, and set them down.

The group, now all seated back on the mismatch of chairs, started to talk. Bourgeois’ son showed up and joined in the conversation, as did the assistants.

Bourgeois was a mostly silent presence on the side of the room. Alert, but speaking little.

Eventually, she stood up heavily on her two canes and walked out.

The salon was over.

Unlike other reports I found, there was no release form, no videotaping, and no other art critic in attendance. Also, no heavy criticism, and no tears.

After leaving, we all spoke for a while outside Bourgeois’ brownstone. I stayed in touch with one of the artists and went to an opening she organized later that year.

Not that long afterward I learned that Louise Bourgeois had died.

I got back in touch with one of the artists who had attended that day and heard the other news. It turned out that we we had been at Bourgeois’ last salon. Seeing how difficult it was for Bourgeois that day, her assistants stopped offering the salons immediately afterward.

I offer this story without a moral, but maybe an observation.

If you live long enough, you’re in effect running a decades-long salon, too. You might have different people in it, hold it more or less often, and offer a different experience. But there may be many people who, after you die, remember you for one brief interaction. Sometimes that makes a difference.